General Raheel Sharif is arguably the most popular Chief of Army Staff so far. He won the people over for acting decisively against terrorism and he deserves accolades for not taking the bait of power and relinquishing the command when the time came.

When Gen Raheel took charge of the Pakistan Army in 2013, the country was struggling to extricate itself from the quagmire of terrorism. Relations with Iran were improving after successful negotiations on the gas pipeline project. The climate seemed promising on the eastern and western borders where a change of leadership took place in 2014. Today, both borders are less than stable and relations with Iran are strained.

According to the South Asia Terrorism Portal, Pakistan’s worst year in terms of terrorist attacks was 2009, when over 11,000 people were killed. This is compared to the lower toll (in the three-digit figures) between 2001 and 2005. It picked up in 2007 and 2008 with over 10,000 casualties in these years. But from 2010 (7,400) to 2014 (5,400), the numbers gradually declined.

This drop in the number of casualties could be attributed to the relocation of the Afghan Taliban and other foreign terrorist groups from Pakistan’s tribal areas to Afghanistan. This change took place after the drawdown of US/NATO forces from Afghanistan and with the launch of the Pakistan Army’s operation in South Waziristan prior to General Raheel. The operation in North Waziristan launched by him also helped reduce terrorism casualties. These figures have come down, with the exception of those of deadly sectarian attacks, which continue uninterrupted. Effective media management helped underplay the coverage of attacks in FATA and of sect-based targeted killings in the rest of the country, but this failed to diminish the threat.

The development of rare public consensus against terrorism and extremism (especially after the 2014 Peshawar APS attack) enabled the army’s expanded control on matters that many would argue are best handled by civilian actors. From the National Action Plan to the Protection Of Pakistan Act, all such initiatives became instruments to maximize the army’s power through apex committees and what became highly politicized operations. The federal and provincial civilian governments, due to their disunity and weaknesses, kept ceding more space to the army that took credit for mediatized successes and accepted blame for all that went wrong. On several occasions the General admonished the civilian government for either poor governance or corruption.

These words resonated well with the people, especially against the backdrop of massive corruption scandals that touched politicians across the spectrum. These scandals rendered the civilian government weaker. General Raheel, however, understood the consequences of a direct take-over quite well and did not choose to go down that road. His intelligent advisors knew that the institution’s interests would be best served if instead of a take-over, the mere threat of one were maintained.

Legendary stories of General Sharif’s hard work, commitment and sacrifice for the country were shared on new media. Information about the usual practice of the army’s internal accountability mechanism was leaked on social media, in order to give the impression of ‘across the board accountability.’ The general’s advisors understood the power of advertising rather well. Indeed, foreign visits reinforced the image of General Sharif who was talking to the world almost in competition with India’s premier Modi who has been rubbing shoulders with the world powers. These stories had a feel-good effect on a people who always yearn for a savior-hero to revere.

The Raheel Doctrine—tough on terrorism—was popularized by a dynamic Inter-Services Public Relations (ISPR), which not only created a legend out of the person of General Raheel but was instrumental in shaping the popular narrative. The downside of overactive media ‘relations’ was that dissenting opinion, even slight questioning, was labeled anti-state. Social media campaigns against dissenters by ‘anonymous’ accounts as well as from talking heads on mainstream media have become the norm in recent years. The electronic media of this era will go down in history for being one in which so many ‘journalists’ have appeared as petty trolls to trade accusations against politicians and independent commentators, otherwise impossible to prove in a court of law. A new TV channel has turned this into regular fare while the rest of the media houses compete with each other for the top slot in the pecking order of bullies.

On the other hand, our TV screens were filled with former officers speaking as defence analysts who held forth as experts on every topic, from irrigation to parliament. We frequently heard top military leadership speaking on foreign policy matters, especially when it came to India, its prime minister and external intelligence agency. Twitter became a means of announcing foreign policy, especially when it came to Iran and Afghanistan. When the spectrum of public opinion is thus limited to a standard, ‘uniform’ view, it ends up hurting the policy makers—which in our case is the army itself.

It would be highly unfair to attribute all of these developments to General Raheel Sharif. This also happened on the watch of a weak Information Ministry and an assertive ISPR. History will be the better judge of who did what to the detriment of building a healthy public discourse. But this certainly provides a general guideline for future leaders on what not to do to ensure long-term stability.

That the institution would become absolutely accountable to civilian oversight is not happening any time soon. Pakistan’s political culture needs to be changed—from the military to the politicians, to the media gurus and other key segments of state and society.

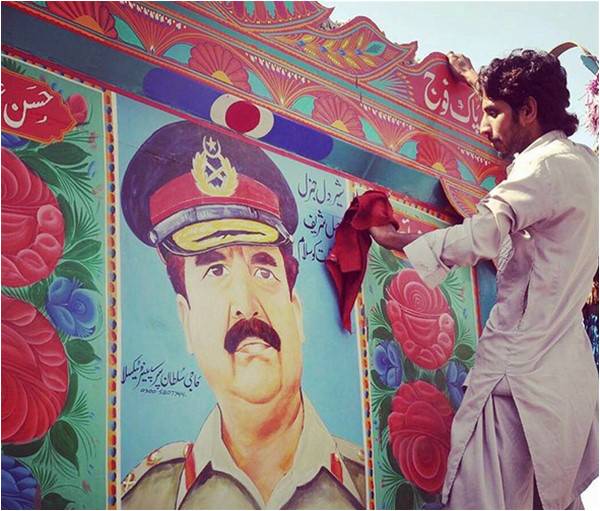

General Qamar Bajwa, the new chief, has expressed his eagerness to work closely with the media and has urged it to refrain from spreading negativity. The hands that hold it might change but the Malacca cane remains the same. It is hoped that General Bajwa will command our powerful forces with professionalism and dedication. In fact, further improving the security of the country and professionalism of the armed forces may be far more important than pursuing the short-lived effects of portraits painted on trucks or placards with the hashtag #ThankYouQamarBajwa.

Marvi Sirmed is an Islamabad-based analyst and political commentator

When Gen Raheel took charge of the Pakistan Army in 2013, the country was struggling to extricate itself from the quagmire of terrorism. Relations with Iran were improving after successful negotiations on the gas pipeline project. The climate seemed promising on the eastern and western borders where a change of leadership took place in 2014. Today, both borders are less than stable and relations with Iran are strained.

According to the South Asia Terrorism Portal, Pakistan’s worst year in terms of terrorist attacks was 2009, when over 11,000 people were killed. This is compared to the lower toll (in the three-digit figures) between 2001 and 2005. It picked up in 2007 and 2008 with over 10,000 casualties in these years. But from 2010 (7,400) to 2014 (5,400), the numbers gradually declined.

This drop in the number of casualties could be attributed to the relocation of the Afghan Taliban and other foreign terrorist groups from Pakistan’s tribal areas to Afghanistan. This change took place after the drawdown of US/NATO forces from Afghanistan and with the launch of the Pakistan Army’s operation in South Waziristan prior to General Raheel. The operation in North Waziristan launched by him also helped reduce terrorism casualties. These figures have come down, with the exception of those of deadly sectarian attacks, which continue uninterrupted. Effective media management helped underplay the coverage of attacks in FATA and of sect-based targeted killings in the rest of the country, but this failed to diminish the threat.

The development of rare public consensus against terrorism and extremism (especially after the 2014 Peshawar APS attack) enabled the army’s expanded control on matters that many would argue are best handled by civilian actors. From the National Action Plan to the Protection Of Pakistan Act, all such initiatives became instruments to maximize the army’s power through apex committees and what became highly politicized operations. The federal and provincial civilian governments, due to their disunity and weaknesses, kept ceding more space to the army that took credit for mediatized successes and accepted blame for all that went wrong. On several occasions the General admonished the civilian government for either poor governance or corruption.

These words resonated well with the people, especially against the backdrop of massive corruption scandals that touched politicians across the spectrum. These scandals rendered the civilian government weaker. General Raheel, however, understood the consequences of a direct take-over quite well and did not choose to go down that road. His intelligent advisors knew that the institution’s interests would be best served if instead of a take-over, the mere threat of one were maintained.

Legendary stories of General Sharif’s hard work, commitment and sacrifice for the country were shared on new media. Information about the usual practice of the army’s internal accountability mechanism was leaked on social media, in order to give the impression of ‘across the board accountability.’ The general’s advisors understood the power of advertising rather well. Indeed, foreign visits reinforced the image of General Sharif who was talking to the world almost in competition with India’s premier Modi who has been rubbing shoulders with the world powers. These stories had a feel-good effect on a people who always yearn for a savior-hero to revere.

The Raheel Doctrine—tough on terrorism—was popularized by a dynamic Inter-Services Public Relations (ISPR), which not only created a legend out of the person of General Raheel but was instrumental in shaping the popular narrative. The downside of overactive media ‘relations’ was that dissenting opinion, even slight questioning, was labeled anti-state. Social media campaigns against dissenters by ‘anonymous’ accounts as well as from talking heads on mainstream media have become the norm in recent years. The electronic media of this era will go down in history for being one in which so many ‘journalists’ have appeared as petty trolls to trade accusations against politicians and independent commentators, otherwise impossible to prove in a court of law. A new TV channel has turned this into regular fare while the rest of the media houses compete with each other for the top slot in the pecking order of bullies.

On the other hand, our TV screens were filled with former officers speaking as defence analysts who held forth as experts on every topic, from irrigation to parliament. We frequently heard top military leadership speaking on foreign policy matters, especially when it came to India, its prime minister and external intelligence agency. Twitter became a means of announcing foreign policy, especially when it came to Iran and Afghanistan. When the spectrum of public opinion is thus limited to a standard, ‘uniform’ view, it ends up hurting the policy makers—which in our case is the army itself.

It would be highly unfair to attribute all of these developments to General Raheel Sharif. This also happened on the watch of a weak Information Ministry and an assertive ISPR. History will be the better judge of who did what to the detriment of building a healthy public discourse. But this certainly provides a general guideline for future leaders on what not to do to ensure long-term stability.

That the institution would become absolutely accountable to civilian oversight is not happening any time soon. Pakistan’s political culture needs to be changed—from the military to the politicians, to the media gurus and other key segments of state and society.

General Qamar Bajwa, the new chief, has expressed his eagerness to work closely with the media and has urged it to refrain from spreading negativity. The hands that hold it might change but the Malacca cane remains the same. It is hoped that General Bajwa will command our powerful forces with professionalism and dedication. In fact, further improving the security of the country and professionalism of the armed forces may be far more important than pursuing the short-lived effects of portraits painted on trucks or placards with the hashtag #ThankYouQamarBajwa.

Marvi Sirmed is an Islamabad-based analyst and political commentator