If there was one thing that could be celebrated as an achievement in India and Pakistan relations on Jammu and Kashmir, it was the ceasefire announced on November 23, 2003. This landmark understanding paved the way for a new chapter in history with two major confidence-building measures rolled out across the Line of Control. Trade was one of them.

In 2013, the ceasefire turned a decade old and thousands of people living along the 725 kilometer LoC were ecstatic about its success and longed for its sustainability. Though violations had interrupted it in between, the hope it would become permanent persisted. After all, it had brought an abrupt end to their sufferings as the guns and shells stopped raining from either side. Tens of thousands of people were able to return to home soon after Pervez Musharraf (the then Pakistan president) announced the ceasefire, immediately reciprocated by New Delhi.

However, it has been derailed in the past three years and in the last few months the violations have surged, with civilians being killed in firing on both sides. The ceasefire is in tatters and the renewed levels of hostility have forced thousands of people from their homes. Since both New Delhi and Islamabad are refusing to return to normalcy, it may take longer to achieve it.

The Pakistan Army has just acquired a new chief in Gen. Qamar Bajwa which is why it is perhaps too early to comment on the outlook on India. For the Modi government in Delhi, however, these levels of hostility might just be acceptable, given the public anger over demonetization and the mood ahead of the elections in Uttar Pradesh that are linked to a hyperbolic attitude towards Pakistan.

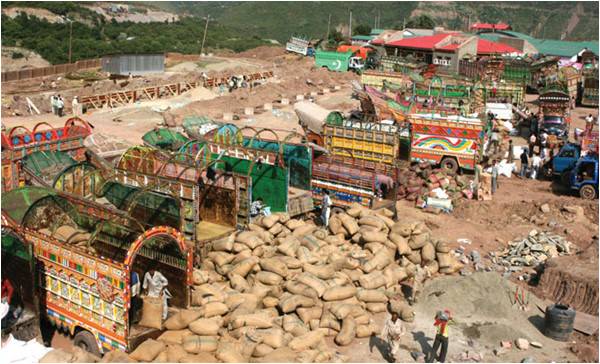

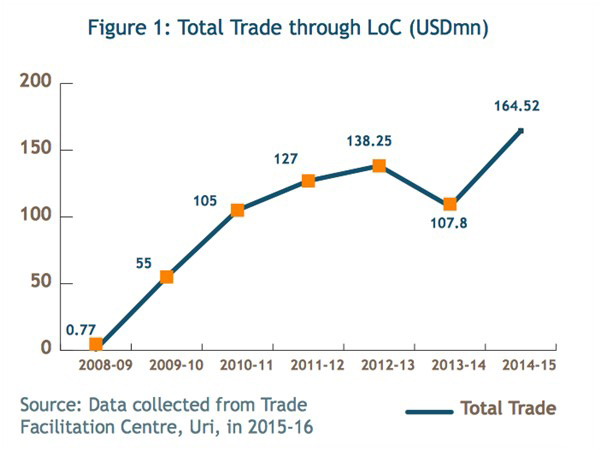

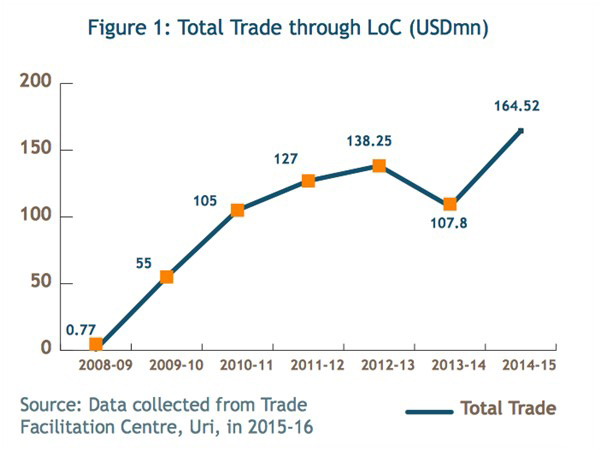

Despite these seemingly difficult ground realities, there is something to cheer about. Cross-LoC trade—that completed eight years on October 21—has emerged as a successful confidence-building measure despite many challenges. This success was examined in a comprehensive report compiled by the Delhi-based Bureau of Research on Industry and Economic Fundamentals in collaboration with the London-based Conciliation Resources. The report was launched in Delhi and Jammu this past week and highlights the progress trade has made in this time period. According to the report, trade worth $699 million has been recorded.

Cross-LoC trade, although agreed upon by India and Pakistan in 2004, only became a reality in 2008 in the wake of protests and strikes during the Amarnath land row. As the trade bodies in Jammu announced an economic blockade, the traders in Kashmir took an emotional recourse by demanding the traditional trade route via Muzaffarabad be re-opened. Subsequently a joint call of “Muzaffarabad Chalo” was given and many people, including senior separatist leader Sheikh Aziz, were killed in police firing when a procession headed there was stopped near Sheeri on the Srinagar-Muzaffarabad road.

New Delhi’s position became precarious so, in order to tackle the brewing resentment it unilaterally moved to give final shape to the cross-LoC trade. Pakistan obliged India and Prime Minister Manmohan Singh and Pakistan President Asif Zardari agreed to opening the routes on September 25 in New York.

This trade has survived despite the absence of a proper mechanism and continued conspiracies against it. This can be seen as a demonstration of the will of the people on both sides to forge unity. Just as with the cross-border bus service, conditions for productive trade have always remained elusive given the ever-tense relations between India and Pakistan. Still trade, which has major symbolic value, has survived. Not only do the shadows of hostilities continue to hover over it, conspiracies ranging from small tiffs between traders to using this route for smuggling narcotics have emerged as a bigger threat. Trade was suspended on both sides multiple times after shelling and firing between the two armies. It was also put on hold for many weeks in 2014 and 2015 when consignments of narcotics were recovered from trucks coming from Pakistan-Administered Kashmir and to date the drivers of the consignment are behind bars in Baramulla jail.

The latest threat to trade came from the traders in Amritsar and Lahore who did not hold back in calling this exchange “illegal and hawala” though the fact is that it is being supervised by two sovereign countries. These traders may have “genuine concerns” over competition for they see this as a parallel trade that is affecting their business. But as the cross-LoC trade was envisioned as a CBM, one needs to look beyond such isolated interests. The CBMs were aimed at encouraging peace in the region. “We will go wrong if we judge this trade by its economical value, because when everything has collapsed, this is only thing which is still going on,” rightly pointed out political scientist Rekha Choudhary at the launch of the report in Jammu (on November 26, 2016). “It has given a notional unity to the erstwhile state of Jammu and Kashmir.”

Rice

Rugs & carpets

Janamaz & tasbies

Precious stones

Wall hangings

Gabbas

Namdas

Peshawari leather chappals

Shawls and stoles

Medicinal herbs

Embroidered items

Maize and maize products

Furniture, including walnut furniture

Kinnow, bananas

Wooden handicrafts

Almonds

Dried pomegranate seed

Honey, moongi, saffron

Tamarind, cumin

Aromatic plants

Black mushroom

Fruit-bearing plants

Dhania

Wooden handicrafts

Kashmiri spices

Rajmah

Papier maché products

Foam mattresses, cushions, pillows

Spring, rubberised coir, and quilts

There are hiccups. Though the Government of India has offered to introduce banking, Pakistan has not been positive in taking it forward. For what it is worth, the traders continued, at an unofficial level, to thrash out differences and remove bottlenecks and set up a Jammu and Kashmir Joint Chamber of Commerce and Industry (KJCCI), the two governments failed to recognize it. JKJCCI is a spectacular achievement of bonhomie on both sides as it has members from the Jammu, Kashmir, Muzaffarabad, Ladakh, Mirpur and Gilgit-Baltistan chambers.

It is ironic that a formula given by current Finance Minister Haseeb Drabu in October 2008 does not find any favour in the government. As an economist who headed Jammu and Kashmir Bank at that time, he had made several suggestions: banking relations, including mutual acceptance of letters of credit, a communication network in order to enable traders to know the rates prevailing on the other side, a transport network, a regulatory network to determine the composition of trade, and a legal network for dispute resolution. The Drabu Formula as it became to be known could have helped make cross-LoC trade meaningful. Whether he stands by his formula today is not known.

And thus, indifference seems to be one other bottleneck from both governments. The people, however, provide the real picture on the ground and it is because of them that trade survives as those associated with it have developed stakes. At the same time it has emerged as a symbol of resistance to hostility and that is what keeps this thread of unity alive.

The writer is the editor-in-chief of the Srinagar-based Rising Kashmir

In 2013, the ceasefire turned a decade old and thousands of people living along the 725 kilometer LoC were ecstatic about its success and longed for its sustainability. Though violations had interrupted it in between, the hope it would become permanent persisted. After all, it had brought an abrupt end to their sufferings as the guns and shells stopped raining from either side. Tens of thousands of people were able to return to home soon after Pervez Musharraf (the then Pakistan president) announced the ceasefire, immediately reciprocated by New Delhi.

However, it has been derailed in the past three years and in the last few months the violations have surged, with civilians being killed in firing on both sides. The ceasefire is in tatters and the renewed levels of hostility have forced thousands of people from their homes. Since both New Delhi and Islamabad are refusing to return to normalcy, it may take longer to achieve it.

The Pakistan Army has just acquired a new chief in Gen. Qamar Bajwa which is why it is perhaps too early to comment on the outlook on India. For the Modi government in Delhi, however, these levels of hostility might just be acceptable, given the public anger over demonetization and the mood ahead of the elections in Uttar Pradesh that are linked to a hyperbolic attitude towards Pakistan.

Despite these seemingly difficult ground realities, there is something to cheer about. Cross-LoC trade—that completed eight years on October 21—has emerged as a successful confidence-building measure despite many challenges. This success was examined in a comprehensive report compiled by the Delhi-based Bureau of Research on Industry and Economic Fundamentals in collaboration with the London-based Conciliation Resources. The report was launched in Delhi and Jammu this past week and highlights the progress trade has made in this time period. According to the report, trade worth $699 million has been recorded.

LoC Trade at a glance

- The nature of the trade is ‘barter’

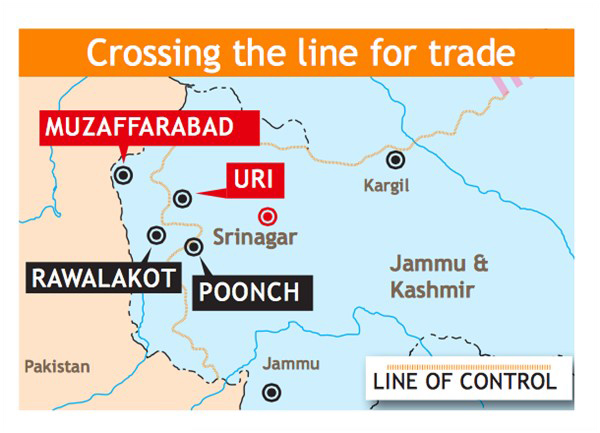

- Trade is allowed through Uri-Muzaffarabad and the Poonch-Rawalakot routes on an agreed list of 21 items

- The trade is carried out according to a Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) signed between New Delhi and Islamabad

- The trade takes place 4 days a week on Tuesday Wednesday, Thursday, and Friday. The trucks must have J&K or AJK registration numbers and should not weigh more than 9 tonnes

- Due to the non-acceptance of LoC as an international border between India and Pakistan, the exports and imports are called ‘traded out’ and ‘traded-in’ goods, respectively

Cross-LoC trade, although agreed upon by India and Pakistan in 2004, only became a reality in 2008 in the wake of protests and strikes during the Amarnath land row. As the trade bodies in Jammu announced an economic blockade, the traders in Kashmir took an emotional recourse by demanding the traditional trade route via Muzaffarabad be re-opened. Subsequently a joint call of “Muzaffarabad Chalo” was given and many people, including senior separatist leader Sheikh Aziz, were killed in police firing when a procession headed there was stopped near Sheeri on the Srinagar-Muzaffarabad road.

New Delhi’s position became precarious so, in order to tackle the brewing resentment it unilaterally moved to give final shape to the cross-LoC trade. Pakistan obliged India and Prime Minister Manmohan Singh and Pakistan President Asif Zardari agreed to opening the routes on September 25 in New York.

This trade has survived despite the absence of a proper mechanism and continued conspiracies against it. This can be seen as a demonstration of the will of the people on both sides to forge unity. Just as with the cross-border bus service, conditions for productive trade have always remained elusive given the ever-tense relations between India and Pakistan. Still trade, which has major symbolic value, has survived. Not only do the shadows of hostilities continue to hover over it, conspiracies ranging from small tiffs between traders to using this route for smuggling narcotics have emerged as a bigger threat. Trade was suspended on both sides multiple times after shelling and firing between the two armies. It was also put on hold for many weeks in 2014 and 2015 when consignments of narcotics were recovered from trucks coming from Pakistan-Administered Kashmir and to date the drivers of the consignment are behind bars in Baramulla jail.

The latest threat to trade came from the traders in Amritsar and Lahore who did not hold back in calling this exchange “illegal and hawala” though the fact is that it is being supervised by two sovereign countries. These traders may have “genuine concerns” over competition for they see this as a parallel trade that is affecting their business. But as the cross-LoC trade was envisioned as a CBM, one needs to look beyond such isolated interests. The CBMs were aimed at encouraging peace in the region. “We will go wrong if we judge this trade by its economical value, because when everything has collapsed, this is only thing which is still going on,” rightly pointed out political scientist Rekha Choudhary at the launch of the report in Jammu (on November 26, 2016). “It has given a notional unity to the erstwhile state of Jammu and Kashmir.”

The items traded across the LoC include:

Rice

Rugs & carpets

Janamaz & tasbies

Precious stones

Wall hangings

Gabbas

Namdas

Peshawari leather chappals

Shawls and stoles

Medicinal herbs

Embroidered items

Maize and maize products

Furniture, including walnut furniture

Kinnow, bananas

Wooden handicrafts

Almonds

Dried pomegranate seed

Honey, moongi, saffron

Tamarind, cumin

Aromatic plants

Black mushroom

Fruit-bearing plants

Dhania

Wooden handicrafts

Kashmiri spices

Rajmah

Papier maché products

Foam mattresses, cushions, pillows

Spring, rubberised coir, and quilts

Source: Ministry of Home Affairs, New Delhi

There are hiccups. Though the Government of India has offered to introduce banking, Pakistan has not been positive in taking it forward. For what it is worth, the traders continued, at an unofficial level, to thrash out differences and remove bottlenecks and set up a Jammu and Kashmir Joint Chamber of Commerce and Industry (KJCCI), the two governments failed to recognize it. JKJCCI is a spectacular achievement of bonhomie on both sides as it has members from the Jammu, Kashmir, Muzaffarabad, Ladakh, Mirpur and Gilgit-Baltistan chambers.

In a perception survey by Conciliation Resources (2015-16), the majority of the traders engaged in cross-LoC trade were reported to be below 40 years of age. Cross-LoC trade has generated employment of 50,000 manpower days in seven years (2008-2015), and

a total income of $117m

It is ironic that a formula given by current Finance Minister Haseeb Drabu in October 2008 does not find any favour in the government. As an economist who headed Jammu and Kashmir Bank at that time, he had made several suggestions: banking relations, including mutual acceptance of letters of credit, a communication network in order to enable traders to know the rates prevailing on the other side, a transport network, a regulatory network to determine the composition of trade, and a legal network for dispute resolution. The Drabu Formula as it became to be known could have helped make cross-LoC trade meaningful. Whether he stands by his formula today is not known.

And thus, indifference seems to be one other bottleneck from both governments. The people, however, provide the real picture on the ground and it is because of them that trade survives as those associated with it have developed stakes. At the same time it has emerged as a symbol of resistance to hostility and that is what keeps this thread of unity alive.

The writer is the editor-in-chief of the Srinagar-based Rising Kashmir