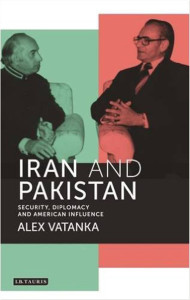

Alex Vatanka

I.B.Taurus, 2015

Pages: 307

Iran-Pakistan relations started off on an undeniably upbeat note. Iran became the first country to diplomatically recognise Pakistan as an independent country and the Shah of Iran was the first foreign Head of State to visit Pakistan in 1950. Quaid-e-Azam Muhammad Ali Jinnah, in 1948 had personally selected Raja Ghazanfar Ali Khan, a veteran Shia politician from Jhelum, as Pakistan’s first Ambassador to Iran.

Raja Ghazanfar Ali Khan, who had served as a Muslim League minister in both Nehru’s interim government and Pakistan’s first cabinets, convinced the host country to waive off visa requirement for Pakistani pilgrims visiting Iran’s religious shrines.

Iran and Pakistan signed a friendship treaty in 1950. By 1958, both countries had agreed to a border agreement and, after two years of negotiations, to a common border which has never been questioned since then. Viewed in the context of Pakistan’s unresolved border problems with India and Afghanistan, this was no mean achievement.

The signing of the friendship treaty marked the advent of the intertwined history of Iran and Pakistan, shaped by political, religious, cultural, social and economic ties. Historically, the Persian language and Sufi preachers from Iran, over the centuries, had a significant impact on the culture of the region constituting Pakistan today.

After Iran, Pakistan is home to the second largest Shia population in the world, who account for around 15-20 percent of the total population of the country. Apart from Jinnah, three of the first four Presidents of Pakistan were Shia.

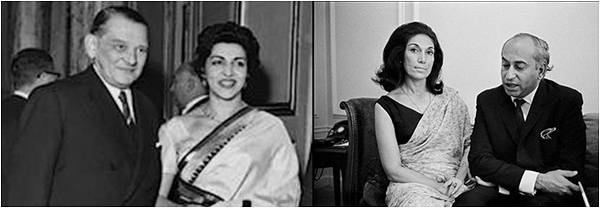

Two of Pakistan’s most influential first ladies - Naheed Iskander Mirza and Nusrat Bhutto - were Iranian. Exiled to London in 1958, Pakistan’s first President Iskander Mirza was buried in 1969 in Tehran after a state funeral by the Iranian government, following Pakistan government’s refusal to permit Naheed to bring back his dead body.

Between I950-1979, Iran was a major source of aid, cash, oil and diplomatic support to Pakistan. During the 1965 and 1971 wars with India, Pakistan Air Force aircraft, for protection from the Indian air force, were stationed in Iran, which also provided arms to Pakistan in both wars, despite repeated Indian protests. Pakistan, due to Iran’s logistical and military help, enjoyed real strategic depth during the two wars with India.

Vatanka shows that it was during the Iranian monarch's time in the 1970s that the slow rupture between the two countries began

Both countries were members of pro-West and anti-communist blocks CENTO and SEATO until 1979. The Shah of Iran served as an effective conduit to the Western countries, specifically the United States, for Pakistan and also mediated between Afghanistan and Pakistan when relations between the two neighbours were strained in the 1960s.

Iran became the largest bilateral donor to Pakistan, providing US $ 800 million in loans and credits between 1974 and 1976. In 1971, Pakistan met its daily consumption of 60,000 barrels per day of crude oil by buying 50,000 barrels from Iran.

Influenced by political confederations of the 1950s between Egypt and Syria and then Jordan and Iraq, the Shah proposed to President Ayub Khan a confederation between Iran and Pakistan with a single army and the Shah as the head of state. The idea of political confederation was again discussed in the 1970s between Iran, Pakistan and Afghanistan.

The standard narrative is that the heyday of Pakistan-Iran relations came during the Shah’s time and the relationship floundered after the Islamic revolution in Iran in 1979, which brought Shia clerics to power - thus providing opportunities to Sunni Arab states in the Gulf to court Pakistan.

Alex Vatanka, a Senior Fellow at Middle East Institute and Jamestown Foundation in Washington DC, has challenged this mainstream view in his well-researched and highly readable book Iran and Pakistan- Diplomacy, Security and American Influence.

Vatanka shows that it was during the Iranian monarch’s time in the 1970s that the slow rupture between the two countries began and although both countries closely collaborated on most issues, there were clearly certain occasions when both competed with each other.

In 1968, when Britain withdrew its forces from the Persian Gulf, Iran thought it was the natural successor to Britain as the policeman of the region. However, Pakistan toyed with the idea of sending its troops to the Gulf States. When the Nixon doctrine favoured Iran, President Ayub Khan backed off.

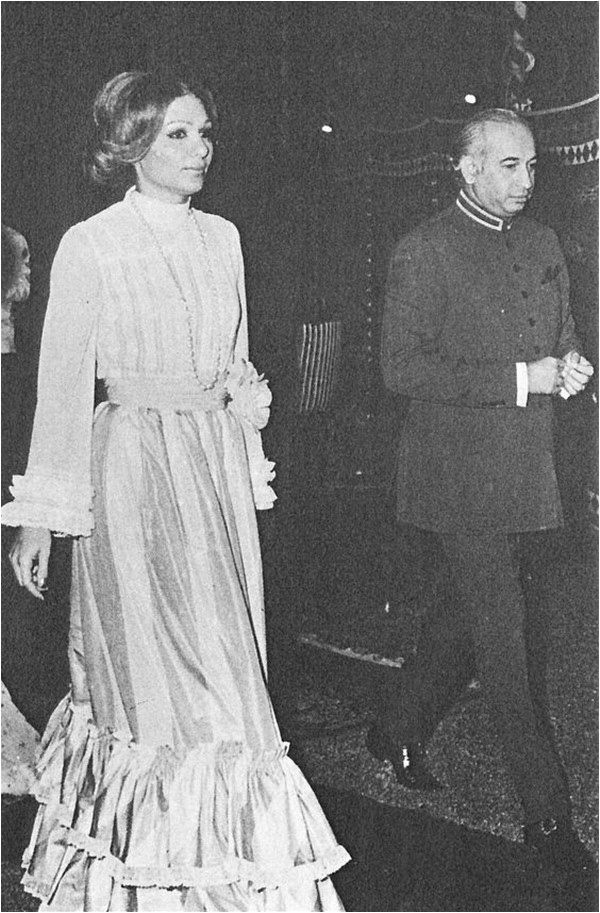

Similarly, both the Shah and Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto vied with each other to offer ports such as Chahabahar and Gawadar respectively to USA as naval bases in the early 1970s. The Shah was irked by this competitive attitude and felt very insecure about Pakistan’s future after its break-up following the 1971 Indo-Pakistan war. The Shah saw himself as Pakistan’s protector and developed a paternalistic attitude towards Pakistan’s leaders, which was resented by Bhutto.

Although both leaders launched a joint operation in Pakistan’s Balochistan region to crush rebellion, the Shah did not like Bhutto’s policy of reaching out to Arab states in the Gulf and stayed away from the 1974 OIC Conference in Lahore.

Later, the Shah made efforts to save Bhutto’s life, when he was in prison, but was upended by the revolution in his own country. Driven to exile three months before Bhutto’s execution, the Shah, wrote Bhutto from his death cell, might have survived “if only he had been a bit more human…if only he had not been such an obnoxious tool of the Western interests”.

Bhutto felt the Shah might have survived "if only he had been a bit more human…if only he had not been such an obnoxious tool of the Western interests"

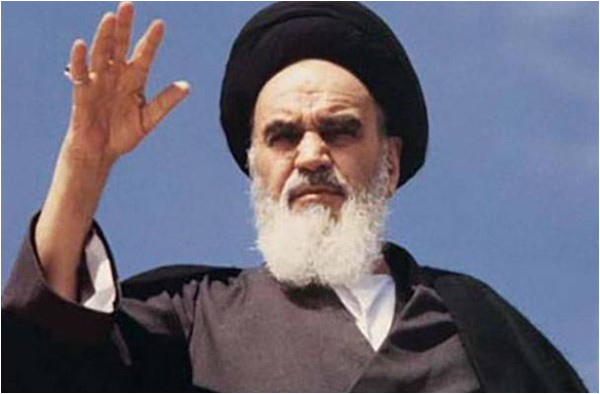

The 1979 Islamic revolution of Iran, in the words of Pakistan’s foremost analyst Eqbal Ahmad, was a landmark event in world history and the twentieth century. He compared it, in historical importance, to the French revolution “in the trends it announced and the fears it aroused among neighbouring ruling elites and in the United States”. However, Pakistan, just few days after Ayatollah Khomeini’s arrival in Tehran, became the first nation to accord diplomatic recognition to his successful revolution.

After the revolution, Iran adopted an explicitly anti-Western foreign policy and viewed President Zia-ul-Haq as an American pawn. Washington nudged Islamabad towards Riyadh after the invasion of Afghanistan by the Soviet Union. Saudi Arabia and the United States financed and armed the Afghan jihad, in which Islamabad played a leading role and pursued a strategy which favoured Saudi-backed mujahedeen groups in Afghanistan.

Iran - although it collaborated with Pakistan on the objective of ousting the Soviets and backed Iran-based Afghan Shia mujahedeen groups - played second fiddle to Islamabad in the Afghan jihad due to its own war with Iraq from 1980-1988.

During the Iran-Iraq war, when Arab Gulf states backed and bankrolled Saddam Hussein’s war effort, Pakistan served as a conduit for Iran to purchase arms from China and North Korea. More importantly, Pakistan, despite pressure from Sunni Arab states, opened the port of Karachi to Iran so that its international trade traffic was shielded from the Iraqi air force, which was targeting Iranian ports. Pakistan-Iran trade more than quadrupled and all this happened when President Zia, known for his anti-Shia and pro-Saudi Islamisation policies, was at the helm.

The book examines in detail the sectarian tensions in Pakistan and the role of a Saudi-Iranian proxy war in exacerbating this divide. However, Vatanka rightly points out that Zia’s Islamisation policies, which pre-dated the Afghan jihad and the Iranian revolution, were most responsible for sectarianism in Pakistan.

Nuclear cooperation between Iran and Pakistan continued throughout the 1990s although both countries pursued divergent and competing aims in Afghanistan at the same time. Bilateral relations hit rock-bottom when the Taliban regime (widely seen as being pro-Islamabad) in Afghanistan murdered Iranian diplomats in Mazar-i-Sharif in 1998.

Iranian policy makers exercised restraint and did not hit back at the Taliban. Tehran’s calculation was that the attack on the consulate had been deliberately carried out to provoke Iran to attack the Taliban, in order to win over Washington’s sympathies and even perhaps diplomatic recognition due to the Taliban’s anti-Iran policy and actions.

US-Iranian antagonism and trust deficit since the 1979 revolution has shaped American foreign policy in the region as Washington has often turned to Pakistan for help in Afghanistan. Tehran had collaborated with Washington in the Bonn conference in 2001 on Afghanistan and helped in getting Hamid Karzai elected as Afghan President. Iran was dismayed when Washington included it in the “Axis of Evil” countries in 2002.

Today Pakistan’s foreign policy makers are focused (some say obsessively) with India and worried about Afghanistan; while Iranian foreign policy is focused on its relations with the Arab neighbours and the Western powers. As a result, both countries, despite geo-strategic rivalry and periodic scuffles at the border, cannot afford antagonistic policies towards each other and feel the need to downplay and resolve their differences.

Economic interdependence and bilateral trade serve as a stabilising factor between any two countries. Pakistan and Iran have a combined population of around 300 million but the bilateral trade is not even US $ 1 billion. This dismal volume is closer to Iran’s trade with its smallest neighbour Armenia (3 million in population) and lesser than Iran-Afghanistan trade of US $ 1.5 billion even though Afghanistan is smaller and impoverished compared to Pakistan. Both countries need to make concrete efforts to overcome this economic disconnect.

Vatanka’s enlightening and insightful analysis is a valuable addition to this under-researched and much neglected subject of Iran-Pakistan relationship. However, the book mostly focuses on the US dimension to Iran-Pakistan relations, both in the Cold War era and after. There is still room for two more books on this topic, one each from the Iranian and Pakistani perspectives respectively.

The writer tweets at @AmmarAliQureshi and can be contacted at ammar_ali@yahoo.com