This past Saturday two young boys lost their lives to bullets fired by the Army’s 10 Garhwal unit, when, according to an army spokesman, they came under an attack by nearly 250 people who threw stones at them.

The tone and tenor of the press release issued by the Defence spokesman in Srinagar suggested that the army men were terrified they were about to be lynched, thus justifying their decision to open fire. This is not the first time that such a justification has been put forward for such a gut-wrenching incident. But this argument of firing in self defense at a mob armed with stones places the army in a weak position. The fact is that the young men were shot in the head and this method was used as the first and only option.

The reaction could have been theoretically avoided if we examine the events that have shaped volatility in Shopian district in South Kashmir. Emotions were running high as a militant had been killed in the area three days earlier. The 44 Rashtriya Rifles (a counter insurgent force) had visited the area to remove posters and black flags (of ISIS) from the graveyard where the militant was buried. They beat a quick retreat as the youth started pelting them with stones. So, the area was already tense.

In the middle of this, an admin convoy of 10 Garhwal passed by. This unit had been called during the Amarnath pilgrimage and had stayed put like many other units had. Without assessing the situation or its sensitivity, they pressed forward as a result of which the locals took their movement as a Cordon and Search Operation, thinking that the 44 RR had called for reinforcement.

More people gathered to put up a resistance. They kept throwing stones and a standoff developed. But the only “solution” the army’s company commander could come up with was to open fire and kill two civilians. Nine people were injured. Police officers confided that the army unit had ignored the ground situation, thus inviting the trouble. The outrage was genuine and on expected lines. Why did the army ignore this and choose to use the option of opening fire as the only one? Immunity would be the answer.

Probes & results

As usual, the state government ordered a magisterial probe. Chief Minister Mehbooba Mufti asserted that the investigation would be taken to its logical conclusion, at the cost of snubbing her coalition partner, the Bharatiya Janata Party. The BJP members of the legislative assembly demanded the withdrawal of the FIR lodged against the Army unit and its Major.

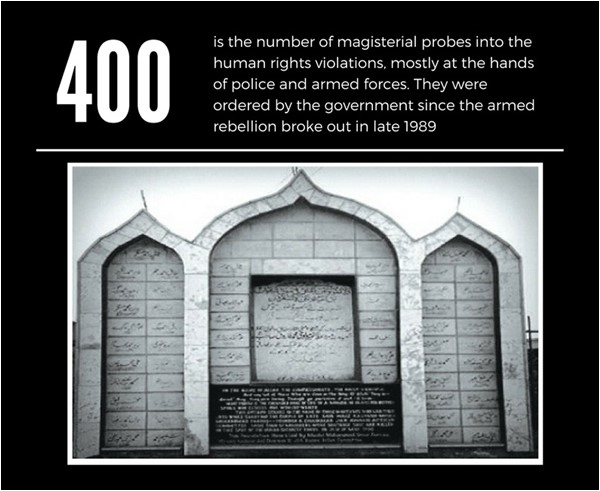

There is nothing new about the probe being ordered. This is a method that has been adopted by successive governments to douse the initial fire. Since the armed rebellion broke out in late 1989, the government must have ordered nearly 400 magisterial probes into the human rights violations, mostly at the hands of police and armed forces. But there are hardly any that can be cited as having been completed or in which the guilty were punished.

In the Hawal massacre of May 1990, 56 civilians were mowed down by the Central Reserve Police Force in what became a classic case. The FIR was registered but to date it has not been closed as the investigation has yet to be completed. There have been an estimated 65,000 FIRs registered since 1990 but no major action has been taken.

From time to time the government has admitted in the state legislature that probes have not been completed. But when an incident like Shopian takes place, a probe is ordered. According to a government report in 13 years (2003 to 2015), 180 probes had been ordered and a majority of them were not concluded. The nature of the killings include custodial killings, firing at civilians, gang rapes, fake encounters, massacres by the security forces.

According to the Jammu and Kashmir Coalition of Civil Society, a human rights organization, the state ordered 33 probes in 2003, 25 inquiries in 2004, 21 in 2005, 11 in 2006 and 12 in 2007. “Since 2003, the state has ordered 168 probes and not even once the inquiries have led to the prosecution of any armed forces personnel,” it said in its report. Justice (retd) M L Koul took 19 months to complete the investigation into the killing of 120 people in 2010 during Omar Abdullah’s chief ministership. He handed over the report to the current chief minister but its finding have yet to be made public. Faith in these investigations and confidence in the state as an institution has been abysmally low.

AFSPA and Army Act

The cry to revoke the Armed Forces Special Powers Act (AFSPA) had been genuinely growing louder with each passing day. The AFSPA has derailed the course of justice when it came to the probes ordered not only by the state government but also those conducted by the Central Bureau of Investigation (the federal agency). The Pathribal fake encounter case is an example.

In almost all cases, the AFSPA has come in handy for the army to evade prosecution. Ironically, in the Pathribal case, instead of losing their job after a foolproof CBI inquiry, the officers were promoted. The same happened with the 1993 Bijbehara massacre in which the Border Security Force personnel were indicted but eventually let off. The latest case is the Machil fake encounter in which a court martial held the army officer guilty of killing three innocent civilians in a fake encounter in 2010. The Armed Forces Tribunal stayed their punishment since the Army Act gives even offenders absolute powers. Ironically, the army has made AFSPA a matter of prestige. When former home minister P. Chidambaram brought certain amendments to the Act, it was stalled by the Defence Ministry and the Army proved to be more powerful than the political leadership. Ignoring the fact that it could help them as an institution, the army has used it as a cover to run away from investigations. Even in civil court they chose to remain absent. For magisterial probes they won’t even respond to summons. The full cover the army enjoys under AFSPA and the Army Act makes these probes meaningless.

Nationalism v. terrorism

Of late, the army has been enjoying support from some TV channels that openly rally behind them, justifying the killings like Shopian. Hashtags such as #StandwithArmy have made the media a part of the state apparatus as they treat every incident in Kashmir as terrorism.

While one can debate anger among the youth and whether stone pelting is a way to vent it, justifying unabashed killings has drawn a clear line between New Delhi and Srinagar. Likewise, the ruling BJP, which is part of the coalition with the Peoples Democratic Party, has made clear its stand of complete immunity to the army.

In such cases, the two coalition partners are not on same page. There is no hope from a probe like this but the fact is that two young men lost their lives. This is unfortunately the new normal in Kashmir.

The tone and tenor of the press release issued by the Defence spokesman in Srinagar suggested that the army men were terrified they were about to be lynched, thus justifying their decision to open fire. This is not the first time that such a justification has been put forward for such a gut-wrenching incident. But this argument of firing in self defense at a mob armed with stones places the army in a weak position. The fact is that the young men were shot in the head and this method was used as the first and only option.

The reaction could have been theoretically avoided if we examine the events that have shaped volatility in Shopian district in South Kashmir. Emotions were running high as a militant had been killed in the area three days earlier. The 44 Rashtriya Rifles (a counter insurgent force) had visited the area to remove posters and black flags (of ISIS) from the graveyard where the militant was buried. They beat a quick retreat as the youth started pelting them with stones. So, the area was already tense.

In the middle of this, an admin convoy of 10 Garhwal passed by. This unit had been called during the Amarnath pilgrimage and had stayed put like many other units had. Without assessing the situation or its sensitivity, they pressed forward as a result of which the locals took their movement as a Cordon and Search Operation, thinking that the 44 RR had called for reinforcement.

More people gathered to put up a resistance. They kept throwing stones and a standoff developed. But the only “solution” the army’s company commander could come up with was to open fire and kill two civilians. Nine people were injured. Police officers confided that the army unit had ignored the ground situation, thus inviting the trouble. The outrage was genuine and on expected lines. Why did the army ignore this and choose to use the option of opening fire as the only one? Immunity would be the answer.

Probes & results

As usual, the state government ordered a magisterial probe. Chief Minister Mehbooba Mufti asserted that the investigation would be taken to its logical conclusion, at the cost of snubbing her coalition partner, the Bharatiya Janata Party. The BJP members of the legislative assembly demanded the withdrawal of the FIR lodged against the Army unit and its Major.

There is nothing new about the probe being ordered. This is a method that has been adopted by successive governments to douse the initial fire. Since the armed rebellion broke out in late 1989, the government must have ordered nearly 400 magisterial probes into the human rights violations, mostly at the hands of police and armed forces. But there are hardly any that can be cited as having been completed or in which the guilty were punished.

In the Hawal massacre of May 1990, 56 civilians were mowed down by the Central Reserve Police Force in what became a classic case. The FIR was registered but to date it has not been closed as the investigation has yet to be completed. There have been an estimated 65,000 FIRs registered since 1990 but no major action has been taken.

From time to time the government has admitted in the state legislature that probes have not been completed. But when an incident like Shopian takes place, a probe is ordered. According to a government report in 13 years (2003 to 2015), 180 probes had been ordered and a majority of them were not concluded. The nature of the killings include custodial killings, firing at civilians, gang rapes, fake encounters, massacres by the security forces.

According to the Jammu and Kashmir Coalition of Civil Society, a human rights organization, the state ordered 33 probes in 2003, 25 inquiries in 2004, 21 in 2005, 11 in 2006 and 12 in 2007. “Since 2003, the state has ordered 168 probes and not even once the inquiries have led to the prosecution of any armed forces personnel,” it said in its report. Justice (retd) M L Koul took 19 months to complete the investigation into the killing of 120 people in 2010 during Omar Abdullah’s chief ministership. He handed over the report to the current chief minister but its finding have yet to be made public. Faith in these investigations and confidence in the state as an institution has been abysmally low.

In the 1990 Hawal massacre, 56 civilians were mowed down by the Central Reserve Police Force. The investigation has yet to be completed

AFSPA and Army Act

The cry to revoke the Armed Forces Special Powers Act (AFSPA) had been genuinely growing louder with each passing day. The AFSPA has derailed the course of justice when it came to the probes ordered not only by the state government but also those conducted by the Central Bureau of Investigation (the federal agency). The Pathribal fake encounter case is an example.

In almost all cases, the AFSPA has come in handy for the army to evade prosecution. Ironically, in the Pathribal case, instead of losing their job after a foolproof CBI inquiry, the officers were promoted. The same happened with the 1993 Bijbehara massacre in which the Border Security Force personnel were indicted but eventually let off. The latest case is the Machil fake encounter in which a court martial held the army officer guilty of killing three innocent civilians in a fake encounter in 2010. The Armed Forces Tribunal stayed their punishment since the Army Act gives even offenders absolute powers. Ironically, the army has made AFSPA a matter of prestige. When former home minister P. Chidambaram brought certain amendments to the Act, it was stalled by the Defence Ministry and the Army proved to be more powerful than the political leadership. Ignoring the fact that it could help them as an institution, the army has used it as a cover to run away from investigations. Even in civil court they chose to remain absent. For magisterial probes they won’t even respond to summons. The full cover the army enjoys under AFSPA and the Army Act makes these probes meaningless.

Nationalism v. terrorism

Of late, the army has been enjoying support from some TV channels that openly rally behind them, justifying the killings like Shopian. Hashtags such as #StandwithArmy have made the media a part of the state apparatus as they treat every incident in Kashmir as terrorism.

While one can debate anger among the youth and whether stone pelting is a way to vent it, justifying unabashed killings has drawn a clear line between New Delhi and Srinagar. Likewise, the ruling BJP, which is part of the coalition with the Peoples Democratic Party, has made clear its stand of complete immunity to the army.

In such cases, the two coalition partners are not on same page. There is no hope from a probe like this but the fact is that two young men lost their lives. This is unfortunately the new normal in Kashmir.