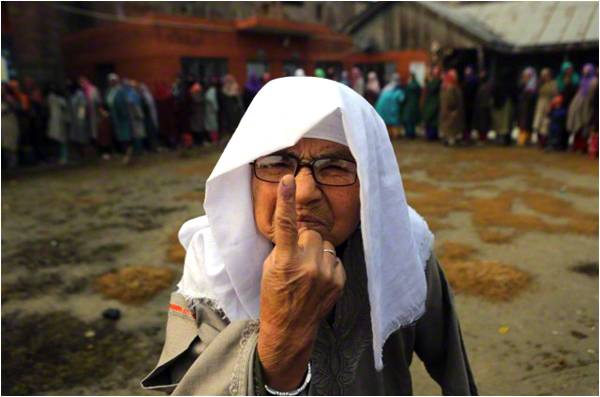

The Indian Jammu and Kashmir state is witnessing a confusing situation in the aftermath of assembly elections that threw up a fractured mandate. A record high turnout notwithstanding, no party is in a position to form a government. Even the game of cobbling up alliances is becoming difficult, since the divergent political ideologies are still keeping the parties away from the negotiating table. To go or not to go, that is the question for the People's Democratic Party (PDP) and the Bhartiya Janta Party (BJP).

The high voter turnout that was witnessed despite a boycott call by separatists was expected to throw a “perfect mandate” but it divided the seats in an interesting manner. In contrast to expectations (of the party) as also the exit poll results, the PDP could not get go even to 35, which could have placed it in a better position. Out of 87 seats, the PDP could get only 28, BJP won 25, National Conference (NC) won 15, Congress 12 and others won seven. In case the PDP had won 35 or more, it might have been in a position to easily join hands with non-BJP forces. Even as the NC offered the support which in every sense was real, and the Congress also extended an unconditional hand, but there seem to be two important issues involved in taking the final decision.

One, that the NC and Congress were voted out of power by the people, and joining the hands with either of them would mean disrespecting the mandate and the will of the people for the change. There is no denying the fact that in contrast to its complete drubbing in Parliament elections held in April 2014, the NC has made a strong comeback by winning 12 seats from Kashmir valley and three from Jammu. Still the anti-incumbency factor was operating during the elections, that cannot be negated. Moreover, the NC and the PDP getting together seems impossible given the inherent “ideological hate” both Abdullah and Mufti families are harbouring against each other. On the other hand, the Congress has won its seats by accident and its performance is based on the candidates in their respective constituencies. Otherwise, people’s ire against Congress that broke all the records of corruption was more evident on the ground. The humiliating defeat the party tasted in its strong bastion and home turf of its stalwart Ghulam Nabi Azad speaks volumes about how people treated the party that had invested so much in the region.

Another important factor that apparently comes in the way of a grand alliance – talked about by senior Congress leader Ghulam Nabi Azad – is that the majority of people in Jammu region have given their mandate to BJP. The mandate is clearer than what we saw in Kashmir valley. The BJP candidates won with huge margins ranging from 45,000 to 10,000 in most constituencies, and that clearly indicates how people threw their weight behind the right wing party. In Kashmir that was not the case, since the margins were thin in most of the segments. So in the process of government formation, it is this mandate that is upsetting any permutation and combination based on the so-called “secular ideologies”. Though there is an element of anti-Kashmir sentiment in the voting pattern in Jammu, at the same time to form a government without the participation of elected representatives of a region may not augur well for the health of the state. Of late there is also a debate going on around the idea of having a different “grand alliance” between PDP, BJP and Congress to ensure that all the three regions of Kashmir, Jammu and Ladakh are on board since Congress won three out of four seats from Ladakh. However, that again looks among the impossibilities as BJP and Congress could only get together in the hereafter. To stitch such an alliance it needs a “grand national interest” to emerge from within the political corridors of Delhi.

Although PDP and BJP are holding “serious” back channel negotiations and have even exchanged papers on crucial issues, it is the most critical phase in the existence of 15-year-old PDP as it makes a final call on the issue. For BJP, it may still be easier to keep the contentious issues off the table and they had already mellowed down the rhetoric on issues such as Article 370, but for PDP it is to do something against a political ideology. BJP is more concerned about being part of the power structure since it has remarkably improved its tally from 11 seats in 2008 to 25 in 2014. Only by coming to power can it consolidate its base and further it in future. So the political ideology could wait.

For PDP it is both – to come into power to survive on the ground, and also to ensure that its political ideology is not diluted to the extent that it is seen as having sold out for the sake of power. As of now, PDP patron Mufti Mohammad Sayeed has widened the spectrum of consultations with his MLA’s and party leaders but is weighing the options considering the fall out of such an alliance. He may become chief minister for six years, but more troubling question is the future of his party.

One argument for a tie up with BJP is that it would ensure development and free flow of funds. That, however, may not be tenable as there are many non-BJP ruled states in India and they don’t necessarily suffer on account of free flow of funds. Similarly, during the Congress rule there have been BJP governments in various states. The larger hurdle that the PDP will have to maneuver around is the political situation in the state. That is why Mufti has pushed forward the “Agenda for Alliance” centering around the engagement with Pakistan, separatists, cross LOC Confidence Building Measures, making a secure environment and bringing respite in the lives of the people. It may be difficult for the BJP to digest such a line of thinking, since Prime Minister Narendra Modi unilaterally called off Foreign Secretary talks in July and has adopted a hard posturing vis a vis Pakistan. But to Mufti’s understanding the route for reconciliation with Pakistan passes through Kashmir and he would like to bargain hard on political issues, rather than development, for the sake of the people who are seeing him and his party as their “saviours” in the mainstream camp.

If at all this alliance comes into existence, it may throw up an opportunity for Modi to tread on Vajpayee’s line of thinking which he has often invoked during the last few months. But for Mufti, a shrewd politician, it may be difficult to join hands with a party that drew a blank in recent elections in Kashmir. To do business with BJP is nothing less than going to the gallows with a hope to survive.

The high voter turnout that was witnessed despite a boycott call by separatists was expected to throw a “perfect mandate” but it divided the seats in an interesting manner. In contrast to expectations (of the party) as also the exit poll results, the PDP could not get go even to 35, which could have placed it in a better position. Out of 87 seats, the PDP could get only 28, BJP won 25, National Conference (NC) won 15, Congress 12 and others won seven. In case the PDP had won 35 or more, it might have been in a position to easily join hands with non-BJP forces. Even as the NC offered the support which in every sense was real, and the Congress also extended an unconditional hand, but there seem to be two important issues involved in taking the final decision.

One, that the NC and Congress were voted out of power by the people, and joining the hands with either of them would mean disrespecting the mandate and the will of the people for the change. There is no denying the fact that in contrast to its complete drubbing in Parliament elections held in April 2014, the NC has made a strong comeback by winning 12 seats from Kashmir valley and three from Jammu. Still the anti-incumbency factor was operating during the elections, that cannot be negated. Moreover, the NC and the PDP getting together seems impossible given the inherent “ideological hate” both Abdullah and Mufti families are harbouring against each other. On the other hand, the Congress has won its seats by accident and its performance is based on the candidates in their respective constituencies. Otherwise, people’s ire against Congress that broke all the records of corruption was more evident on the ground. The humiliating defeat the party tasted in its strong bastion and home turf of its stalwart Ghulam Nabi Azad speaks volumes about how people treated the party that had invested so much in the region.

It is like going to the gallows with a hope to survive

Another important factor that apparently comes in the way of a grand alliance – talked about by senior Congress leader Ghulam Nabi Azad – is that the majority of people in Jammu region have given their mandate to BJP. The mandate is clearer than what we saw in Kashmir valley. The BJP candidates won with huge margins ranging from 45,000 to 10,000 in most constituencies, and that clearly indicates how people threw their weight behind the right wing party. In Kashmir that was not the case, since the margins were thin in most of the segments. So in the process of government formation, it is this mandate that is upsetting any permutation and combination based on the so-called “secular ideologies”. Though there is an element of anti-Kashmir sentiment in the voting pattern in Jammu, at the same time to form a government without the participation of elected representatives of a region may not augur well for the health of the state. Of late there is also a debate going on around the idea of having a different “grand alliance” between PDP, BJP and Congress to ensure that all the three regions of Kashmir, Jammu and Ladakh are on board since Congress won three out of four seats from Ladakh. However, that again looks among the impossibilities as BJP and Congress could only get together in the hereafter. To stitch such an alliance it needs a “grand national interest” to emerge from within the political corridors of Delhi.

Although PDP and BJP are holding “serious” back channel negotiations and have even exchanged papers on crucial issues, it is the most critical phase in the existence of 15-year-old PDP as it makes a final call on the issue. For BJP, it may still be easier to keep the contentious issues off the table and they had already mellowed down the rhetoric on issues such as Article 370, but for PDP it is to do something against a political ideology. BJP is more concerned about being part of the power structure since it has remarkably improved its tally from 11 seats in 2008 to 25 in 2014. Only by coming to power can it consolidate its base and further it in future. So the political ideology could wait.

For PDP it is both – to come into power to survive on the ground, and also to ensure that its political ideology is not diluted to the extent that it is seen as having sold out for the sake of power. As of now, PDP patron Mufti Mohammad Sayeed has widened the spectrum of consultations with his MLA’s and party leaders but is weighing the options considering the fall out of such an alliance. He may become chief minister for six years, but more troubling question is the future of his party.

One argument for a tie up with BJP is that it would ensure development and free flow of funds. That, however, may not be tenable as there are many non-BJP ruled states in India and they don’t necessarily suffer on account of free flow of funds. Similarly, during the Congress rule there have been BJP governments in various states. The larger hurdle that the PDP will have to maneuver around is the political situation in the state. That is why Mufti has pushed forward the “Agenda for Alliance” centering around the engagement with Pakistan, separatists, cross LOC Confidence Building Measures, making a secure environment and bringing respite in the lives of the people. It may be difficult for the BJP to digest such a line of thinking, since Prime Minister Narendra Modi unilaterally called off Foreign Secretary talks in July and has adopted a hard posturing vis a vis Pakistan. But to Mufti’s understanding the route for reconciliation with Pakistan passes through Kashmir and he would like to bargain hard on political issues, rather than development, for the sake of the people who are seeing him and his party as their “saviours” in the mainstream camp.

If at all this alliance comes into existence, it may throw up an opportunity for Modi to tread on Vajpayee’s line of thinking which he has often invoked during the last few months. But for Mufti, a shrewd politician, it may be difficult to join hands with a party that drew a blank in recent elections in Kashmir. To do business with BJP is nothing less than going to the gallows with a hope to survive.