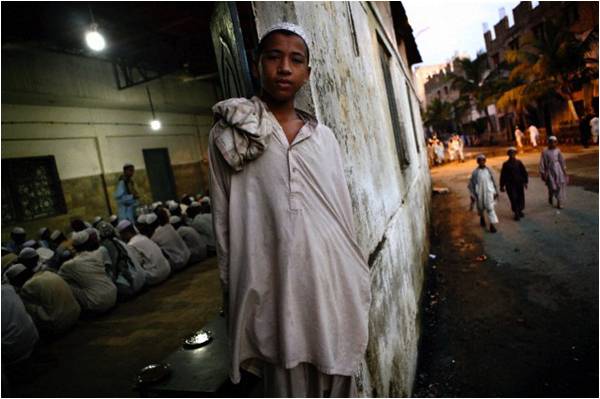

In the recently approved National Plan of Action (NPA), the government has once again spoken about freeing madrassas from the shackles of extremism, calling for the registration and regulation of every single seminary. It proposes a ban on unauthorized religious schools.

The PML-Nawaz government and especially its Interior Minister Chaudhry Nisar Ali Khan are pinning their hopes on two gentleman to help them make that possible.

Mufti Saleemullah Khan heads the Ittehad-e-Tanzimat-e-Madaris-e-Deeniya – a conglomerate of five private educational boards that operates 20,000 seminaries. Qari Hanif Jalandhari is secretary general of the board, or the Wafaq.

Successive governments have spent billions of rupees on madrassa reform projects, since a number of notorious militants were associated with various seminaries before they went on killing sprees “in the name of Islam.” The top management of the Wafaq has always rejected allegations of spreading extremism and preaching violence.

Mufti Eid Muhammad, the explosives expert of the defuct Lashkar-e-Jhangvi who was arrested in Lahore in 2005, was reportedly a student of a seminary run by Mufti Saleemullah Khan, and later got a teaching job in the same seminary. His association with the seminary spanned more than seven years. Eid Muhammad was accused of being involved in a deadly attack on the ISI headquarters in Multan. He was also allegedly a part of the group that carried out a terrorist attack in Lahore’s Moon Market.

Hanif Jalandhari is skeptical of most plans of madrassa reforms. He runs the affairs of Kherul Madaris, a seminary located in Multan. Among its students was Hafiz Gul Bahadur, a notorious Taliban commander in Waziristan.

Some argue that their decision to become militants must have come out of their deep ideological upbringing. The seminaries they went to must have provided fertile grounds for their radicalization, they say.

How to modernize seminaries and their syllabi is a complex and controversial topic. Their sources of funding is yet another tricky subject. A few months ago, the interior ministry claimed there were more than 500 seminaries that fomented extremism and accepted funds from foreign donors. The seminaries rejected it saying Muslim charities did provide financial assistance, but for the welfare of the students.

The ministry divided the seminaries into four categories: the A-category seminaries were identified as potential threats, B-category as highly sensitive, C-category as sensitive and D-category as non-extremist. A majority of madrassas falls in the D-category.

A couple of years ago, the Punjab government made registration mandatory for new seminaries. It also tried to convince them to teach English, mathematics, sciences, computers and modern languages. The policy failed. If a modern education could stop extremism, the Punjab University would have been full of students talking reason.

In 2001, Gen Musharraf formed the Pakistan Madrassa Education Board (PMEB) to modernize traditional religious seminaries and counter extremism.

“In June 2002, the Deeni Madaris (Voluntary Registration and Regulation) Ordinance 2002 was approved. The new law required religious schools to register with the PMEB and to have their sources of funding monitored, and anyone found teaching sectarian hatred in a madrassa could be jailed for two years,” according to a policy brief by Jinnah Institute.

Over 300 madrassas got themselves affiliated with the PMEB, but a majority of them saw the project as unnecessary official intervention in what they believed was their exclusive domain. They believed the move was aimed at de-Islamizing Pakistan at the behest of Western powers.

Published last year, the National Internal Security Policy (NISP) noted that more than 22,000 madrassas were operating in the country. The document said – and it revealed no secret – that some of them were fanning extremism that led to terrorism. “There were problems within some madrassas which have spread extremism,” the policy statement said. They received funding from unidentified sources, and published and distributed hate literature.

It calls for building a national narrative against extremism and terrorism. While that cannot be done without the help of people who run madrassas, there are also legitimate questions about whether they are willing to contribute towards this goal. That is the government’s dilemma.

Shahzad Raza is an Islamabad-based journalist

Twitter: @shahzadrez

The PML-Nawaz government and especially its Interior Minister Chaudhry Nisar Ali Khan are pinning their hopes on two gentleman to help them make that possible.

Mufti Saleemullah Khan heads the Ittehad-e-Tanzimat-e-Madaris-e-Deeniya – a conglomerate of five private educational boards that operates 20,000 seminaries. Qari Hanif Jalandhari is secretary general of the board, or the Wafaq.

Successive governments have spent billions of rupees on madrassa reform projects, since a number of notorious militants were associated with various seminaries before they went on killing sprees “in the name of Islam.” The top management of the Wafaq has always rejected allegations of spreading extremism and preaching violence.

If modern education could stop extremism, Punjab University would be full of students talking reason

Mufti Eid Muhammad, the explosives expert of the defuct Lashkar-e-Jhangvi who was arrested in Lahore in 2005, was reportedly a student of a seminary run by Mufti Saleemullah Khan, and later got a teaching job in the same seminary. His association with the seminary spanned more than seven years. Eid Muhammad was accused of being involved in a deadly attack on the ISI headquarters in Multan. He was also allegedly a part of the group that carried out a terrorist attack in Lahore’s Moon Market.

Hanif Jalandhari is skeptical of most plans of madrassa reforms. He runs the affairs of Kherul Madaris, a seminary located in Multan. Among its students was Hafiz Gul Bahadur, a notorious Taliban commander in Waziristan.

Some argue that their decision to become militants must have come out of their deep ideological upbringing. The seminaries they went to must have provided fertile grounds for their radicalization, they say.

How to modernize seminaries and their syllabi is a complex and controversial topic. Their sources of funding is yet another tricky subject. A few months ago, the interior ministry claimed there were more than 500 seminaries that fomented extremism and accepted funds from foreign donors. The seminaries rejected it saying Muslim charities did provide financial assistance, but for the welfare of the students.

The ministry divided the seminaries into four categories: the A-category seminaries were identified as potential threats, B-category as highly sensitive, C-category as sensitive and D-category as non-extremist. A majority of madrassas falls in the D-category.

A couple of years ago, the Punjab government made registration mandatory for new seminaries. It also tried to convince them to teach English, mathematics, sciences, computers and modern languages. The policy failed. If a modern education could stop extremism, the Punjab University would have been full of students talking reason.

In 2001, Gen Musharraf formed the Pakistan Madrassa Education Board (PMEB) to modernize traditional religious seminaries and counter extremism.

“In June 2002, the Deeni Madaris (Voluntary Registration and Regulation) Ordinance 2002 was approved. The new law required religious schools to register with the PMEB and to have their sources of funding monitored, and anyone found teaching sectarian hatred in a madrassa could be jailed for two years,” according to a policy brief by Jinnah Institute.

Over 300 madrassas got themselves affiliated with the PMEB, but a majority of them saw the project as unnecessary official intervention in what they believed was their exclusive domain. They believed the move was aimed at de-Islamizing Pakistan at the behest of Western powers.

Published last year, the National Internal Security Policy (NISP) noted that more than 22,000 madrassas were operating in the country. The document said – and it revealed no secret – that some of them were fanning extremism that led to terrorism. “There were problems within some madrassas which have spread extremism,” the policy statement said. They received funding from unidentified sources, and published and distributed hate literature.

It calls for building a national narrative against extremism and terrorism. While that cannot be done without the help of people who run madrassas, there are also legitimate questions about whether they are willing to contribute towards this goal. That is the government’s dilemma.

Shahzad Raza is an Islamabad-based journalist

Twitter: @shahzadrez