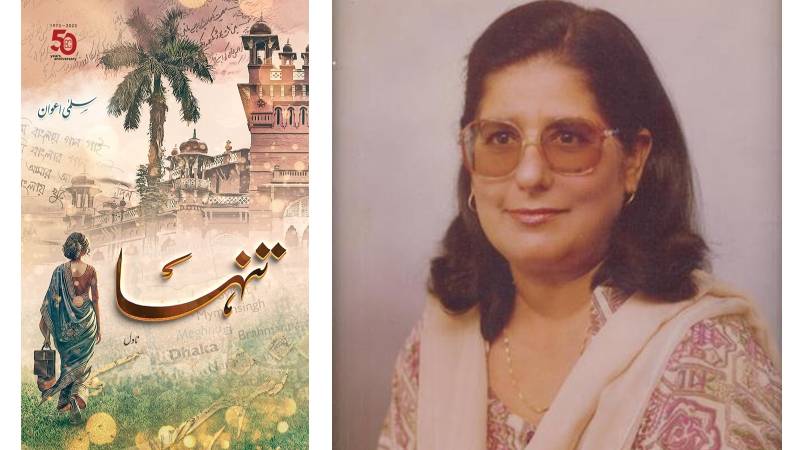

Completed within a month of the Fall of Dhaka and offered to a publisher, it took eight years and trips to five different publishers before Tanha was finally published in 1979. An extraordinary novel because of the boldness, objectivity and nuance with which it approaches the sensitive and highly emotive theme of events that led up to secession and sundering of Pakistan, so proximate as its creation was both spatially and temporally to what transpired. Equally extraordinary is how difficult we still find it to talk about this bleak chapter of our past, how denuded our teaching of history of meaningful texts like this, and how intransigent our State about not learning from this debacle.

Recently republished in an elegant edition by Book Corner Jhelum, this is a book that I would enthusiastically recommend for developing a deeper appreciation of how a people drift apart and the subsequent painful phases of disenchantment, distancing, dismay and divorce. Under the present sun, as others amongst our compatriots undergo this debilitating despondence and desperately protest at their forced alienation, such texts are obviously not just of value due to their literary merit and historical value, but vitally due to the politics of coming together that they extol — a politics that we don’t teach, don’t practice, and don’t allow to germinate and flourish. No wonder a spreading wasteland where diktat increasingly reigns supreme, as we witness with horror the shrinking space for what it means to be a citizen.

In Tanha, however, citizens remain central even as tumultuous, life-changing, epoch-defining events surround them. Samia Ali or Somi, as she is fondly called, is a vivacious young woman from West Pakistan who opts to travel to be a student at Dhaka University. She is welcomed and often hosted there by a local Bengali family that has deep and abiding bonds with her family. Fascinated and charmed by the cultural and natural lushness of her new surroundings, overwhelmed by the affection of her host family, and progressively persuaded by her adopted locale to revisit many of her strongly held notions about nationhood, patriotism and identity, she is a compelling protagonist.

The novel’s other main character is the eldest son of the host family — Ijtiba-ur-Rehman, fondly known as Shilpi, a top-notch Oxford educated lawyer and a firebrand and highly popular young political leader. Samia quickly finds herself at odds with him, both temperamentally as well as due to their diametrically opposed views on history and politics. Samia is a patriot who passionately believes in a united country and looks down upon all talks of separatism with horror and disdain. She harbours too, at least initially, some of the typical racial and cultural prejudices about East Pakistanis, and also encounters similar bigotry and prejudice directed against her and those like her from some of the more radicalised Bengalis.

Ijtiba-ur-Rehman, on the other hand, has shifted from one kind of patriotism to another; a shift that has been brought about by disenchantment and increasing bitterness about his people getting a raw deal. Both him and Samia don’t lack conviction as well as good arguments, and this is where the author is so successful and adept in capturing multiple facets of complex realities. The charismatic young politician is a strident critic of what he sees as political and economic hegemony and exploitation by the Western wing. Years of political meditations and activism have now propelled him to be amongst those who lead and drive a movement for emancipation from what they see as the yoke of a rapacious ruling elite sitting a thousand miles away.

Salma Awan graduated from Dhaka University in 1970. Expose as it intimately did her to the special way of life of that place at that time, her experience there evidently also imbued and enriched her world view with nuance, objectivity, sensitivity and capacity to embrace complexity, contradictions, paradoxes and the potential credibility and merit of more attitudes and approaches than one.

As the political intertwines with the romantic in the novel, the irrepressible Samia Ali finds that even love can’t overcome divides and gulfs that are triggered by a sense of injustice and pain

Above all, it is, as the narrative divulges, a deep empathy that allows her to step aside from entrenched statist, ethnic and cultural positions and dismantle and dissect ideologies and events to examine them at a fundamental human level. This is resonant in what is a generous and compassionate authorial voice in the novel. As a result, she is subtle and highly perceptive in how she portrays Samia questioning many of her staunchly held assumptions, notions and prejudices.

Remaining faithful to her conviction that division is no solution and actually abhorrent, that any and all differences can be resolved, and mistakes and outrages undone, and that a rupture is short-sighted, parochial and disastrous, fuelled also by intriguers and mischief-makers, she finds herself much altered over the months. And that is because she cannot watch and listen and learn and ponder and then deny the consequences of and resentment at a dispensation received by a land that is visibly much less loved by those in power.

Valiantly, especially at the deeply emotive, painful and polarised time when the country broke up, Salma Awan produces descriptions and dialogues highly critical of the inequitable political and economic treatment of East Pakistan, the hubris and apathy of administrators civil and military, the highly ill-advised language policy and imposition of Urdu, and criminally inept handling of a rapidly worsening situation, as angst, ire and rebelliousness spread through university campuses and the general populace like a wild fire. What she wrote was forthright and valiant then. It remains forthright and valiant today. Where many a publisher was timid and tremulous, she remained resolute that she wanted to publish precisely what she had experienced, felt and written.

As the political intertwines with the romantic in the novel, the irrepressible Samia Ali finds that even love can’t overcome divides and gulfs that are triggered by a sense of injustice and pain. In many ways what transpires embodies Faiz’s haunting lines:

ہم کے ٹھہرے اجنبی اتنی ملاقاتوں کے بعد

Hum Kai Thehray Ajnabi Itni Mulaqaton Kai Bad

For a novel so deeply steeped in emotions of alienation, resentment, regret and loss, Tanha is often wonderfully evocative and rejoicing, rich in description and at times even humorous. The novelist is also a much travelled and acclaimed travel writer, and her descriptive skills are on evident display. Dhaka, Barisal, Sylhet, Narayanganj, Khulna, Sundarbans, Chittagong, Cox’s Bazaar, old shrines, the waterscapes and countryside — it is enthralling to read descriptions of these places from someone who visited them at that critical juncture and gazed upon them with an affection bordering on adoration.

Salma Awan also evokes with loving detail the flora, topography, historical quarters, cuisine, customs, poetry, movies, and the fabulous music of Bengal, underlining again the richness of what it offers and what was not truly cherished and valued. Verses from Tagore and Nazrul Islam adorn her narrative as she makes converts of us, as she does also of her protagonist, to the charms of Bengal ka Jadu and the warmth of its people. Yet even while wringing her hands at her growing sense of loss, her protagonist never stops pointing fingers at intriguers, rabble-rousers, opportunists and miscreants who successfully exploited the real, felt and imagined popular grievances. But one finds this neither paradoxical nor contradictory as the complexity of the milieu understandably provokes very mixed and at times muddled emotions and assessments.

At the level of art and craft, the novel’s language flows, the descriptions and dialogues are lively and sharp, and very seldom do things become melodramatic. Importantly, the authorial voice is never didactic or definitive but invariably reflective and sensitive. As mentioned, a romance blossoms during the turbulent year in which the novel is set and amidst the debris of failed policies, growing campus violence, bloody language riots, and disastrous political caprice. Importantly, we are persuaded to appreciate that at a fundamental human level a deep bond can help potentially overcome so many divides. That Porbo Pakistan and Panchamo Pakistan could have remained together if those who called the shots had the same sense of collectivity and connection, as indeed many of the denizens of these places did — a people so callously torn apart.