In 1995, I appeared for the Federal Board of Intermediate and Secondary Education exams for overseas Pakistani students in the Middle East. To this date I can recite that “the form of the future constitution shall be federal with residuary powers vested in the provinces” and that “in the central legislature, the Mussulman representation shall not be less than one third”.

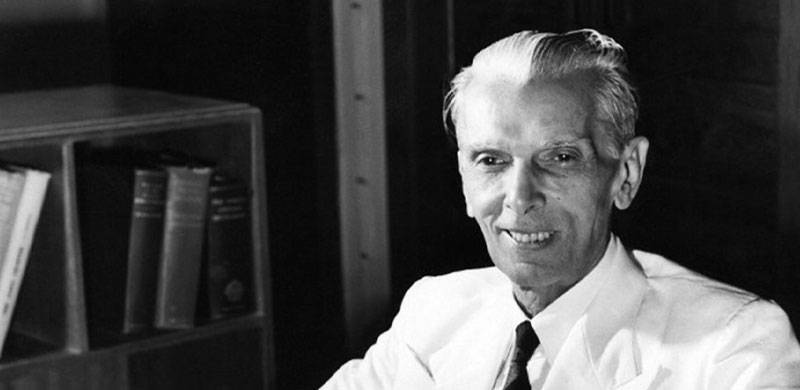

This in a nutshell captures the thrust of Jinnah’s 14 points. Muhammad Ali Jinnah, a man who millions of Pakistanis revere as the Quaid-e-Azam (the great leader). They honour him, as Pakistan for them is a revolt against minority status in Bharat (ancient land of India) with Hindu hegemony. They reject the Indian Hindu narrative that sees Muslims as foreigners that arrived in the Indian subcontinent as imperial colonialists or at best, as converts who had gone astray from their sanatan dharma (Hindu faith) and who, therefore, must be called back to their original faith through ghar waapsi (return home) schemes.

Indeed, I was also taught about the shuddhi (purification) and sangathan (solidarity) Hindu movements against the Muslims.

I had studied in an Indian school system until the sixth grade, where we were taught about the ancient Mauryan Empires. However, Pakistan Studies, as I remember it, did not dwell much on them or for that matter the Mughal Empire. Instead, the focus was on the concerns of minority Muslims of the Indian subcontinent, whose aspirations were projected by Sir Syed Ahmad Khan in the 19th century and by Jinnah in the 20th century.

In our school, I belonged to the Jinnah House (green), whereas my classmates belonged to the Liaquat (red), Sir Syed (yellow) and Iqbal (blue) houses. Around that time or perhaps a year earlier, the late Prime Minister Benazir Bhutto declared a holiday for Kashmir Day. Our school principal, a Pakistani Christian, who was quite keen on my academic performance, followed the directive. The next we heard was that the Arab government was deporting him for a political stunt. To this date I reflect on the poor treatment he must have received from both Pakistanis and Arabs.

Indeed, where Pakistan was meant to be a haven from majoritarian persecution, the country – one-seventh the size of India – turned around to oppress its own minorities with the increasing Islamisation of the state.

There is no dearth of patriotic Pakistani Christians, Pakistani Hindus, and Ahmadis. I think of them when I witness the revival of Hindu fascism in India. I focus on them, as Indian Muslims have their own narrative. They remain deeply loyal to India, and they are more than capable of addressing their issues in their home state. Their concerns are not Pakistani concerns. Indeed, no two Muslims think alike, and so when Jinnah raised the clarion call, a constellation of secular Muslims, Ahmadis, Dalits, Parsis, and Punjabi Christians answered.

On the other hand, the reactionary conservative Muslims and others who followed Maulana Azad sided with the Congress. Indeed, Pakistan was meant for minorities and not for hardcore Islamists, like the Majlis Ahrar or Jamaat Islami, that usurped the Pakistani narrative after Jinnah’s untimely death.

However, the persecution of Muslim minorities in India serves as a reflection in the mirror, for much needs to be done to address the concerns of minorities in Pakistan. It is an opportunity for Pakistan to do better than India, which would be feasible if we resuscitate the story of Pakistan, as a haven for the oppressed minorities and not as an Islamist project, which is being rivalled by Hindu fascists in India.

The story of Pakistan that includes Pakistani Christians, Pakistani Hindus, Ahmadis, any and all, is available in the works of Yasser Latif Hamdani, who has already written two excellent books on Jinnah. I have reviewed his latest book Jinnah: A Life, although his 2012 book, Jinnah: Myth , and Reality, seems more appropriate to project a Pakistani narrative that deserves to be safeguarded from the clutches of Islamists and the propaganda of Hindu fascists. This narrative, based on Hamdani’s text, can be projected in bullet point form, as follows.

The narrative that emerges from these 20 bullet points is clear. Pakistan was never meant to be an Islamic state but a haven for the Muslim minority of India that was joined by Dalits under Jogendra Nath Mandal. Jinnah’s own words stand as a testament on Ahmadis, the popular Pakistan slogan, Pakistani Hindus, and the state of Pakistan, as follows.

“What right have I to declare a person non-Muslim, when he claims to be a Muslim”.

“Neither I nor the Muslim League working committee ever passed a resolution – Pakistan ka matlab kya – you may have used it to catch a few votes”.

“We do not prescribe any schoolboy tests for their loyalty. We shall not say to any Hindu citizen of Pakistan, ‘if there was war would you shoot a Hindu?’”

“In any case Pakistan is not going to be a theocratic state – to be ruled by priests with a divine mission. We have many non-Muslims – Hindus, Christians, and Parsis – but they are all Pakistanis”.

My days of studying Pakistan Studies to write exams are long over. Though, I hope that the Pakistan narrative and curriculum builders invite Yasser Latif Hamdani and upcoming authors like Muhammad Umair Khan, to help them guide the newer generation of Pakistani students through their research, which can be disseminated through short five to ten minute videos. It is their voices that are much needed to honour Jinnah and the Pakistan movement. Lest we forget!

This in a nutshell captures the thrust of Jinnah’s 14 points. Muhammad Ali Jinnah, a man who millions of Pakistanis revere as the Quaid-e-Azam (the great leader). They honour him, as Pakistan for them is a revolt against minority status in Bharat (ancient land of India) with Hindu hegemony. They reject the Indian Hindu narrative that sees Muslims as foreigners that arrived in the Indian subcontinent as imperial colonialists or at best, as converts who had gone astray from their sanatan dharma (Hindu faith) and who, therefore, must be called back to their original faith through ghar waapsi (return home) schemes.

Indeed, I was also taught about the shuddhi (purification) and sangathan (solidarity) Hindu movements against the Muslims.

I had studied in an Indian school system until the sixth grade, where we were taught about the ancient Mauryan Empires. However, Pakistan Studies, as I remember it, did not dwell much on them or for that matter the Mughal Empire. Instead, the focus was on the concerns of minority Muslims of the Indian subcontinent, whose aspirations were projected by Sir Syed Ahmad Khan in the 19th century and by Jinnah in the 20th century.

In our school, I belonged to the Jinnah House (green), whereas my classmates belonged to the Liaquat (red), Sir Syed (yellow) and Iqbal (blue) houses. Around that time or perhaps a year earlier, the late Prime Minister Benazir Bhutto declared a holiday for Kashmir Day. Our school principal, a Pakistani Christian, who was quite keen on my academic performance, followed the directive. The next we heard was that the Arab government was deporting him for a political stunt. To this date I reflect on the poor treatment he must have received from both Pakistanis and Arabs.

Indeed, where Pakistan was meant to be a haven from majoritarian persecution, the country – one-seventh the size of India – turned around to oppress its own minorities with the increasing Islamisation of the state.

Pakistan Studies did not dwell much on them or for that matter the Mughal Empire. Instead, the focus was on the concerns of minority Muslims of the Indian subcontinent, whose aspirations were projected by Sir Syed Ahmad Khan in the 19th century and by Jinnah in the 20th century.

There is no dearth of patriotic Pakistani Christians, Pakistani Hindus, and Ahmadis. I think of them when I witness the revival of Hindu fascism in India. I focus on them, as Indian Muslims have their own narrative. They remain deeply loyal to India, and they are more than capable of addressing their issues in their home state. Their concerns are not Pakistani concerns. Indeed, no two Muslims think alike, and so when Jinnah raised the clarion call, a constellation of secular Muslims, Ahmadis, Dalits, Parsis, and Punjabi Christians answered.

On the other hand, the reactionary conservative Muslims and others who followed Maulana Azad sided with the Congress. Indeed, Pakistan was meant for minorities and not for hardcore Islamists, like the Majlis Ahrar or Jamaat Islami, that usurped the Pakistani narrative after Jinnah’s untimely death.

However, the persecution of Muslim minorities in India serves as a reflection in the mirror, for much needs to be done to address the concerns of minorities in Pakistan. It is an opportunity for Pakistan to do better than India, which would be feasible if we resuscitate the story of Pakistan, as a haven for the oppressed minorities and not as an Islamist project, which is being rivalled by Hindu fascists in India.

The story of Pakistan that includes Pakistani Christians, Pakistani Hindus, Ahmadis, any and all, is available in the works of Yasser Latif Hamdani, who has already written two excellent books on Jinnah. I have reviewed his latest book Jinnah: A Life, although his 2012 book, Jinnah: Myth , and Reality, seems more appropriate to project a Pakistani narrative that deserves to be safeguarded from the clutches of Islamists and the propaganda of Hindu fascists. This narrative, based on Hamdani’s text, can be projected in bullet point form, as follows.

- Jinnah upheld equality when he consistently opposed Muslims on separate electorates and campaigned to get Indians the right to serve as equal officers.

- Jinnah’s Lucknow Pact sacrificed Muslim majority in key Muslim provinces for better representation in Muslim minority provinces.

- Jinnah took a principled stand against the British colonial power by representing Ilam Din based on his age, Bal Gangadhar Tilak against sedition charges, as well as Bhagat Singh.

- Jinnah upheld socially progressive causes by supporting inter-communal marriage, being instrumental in passing the bill on restraining child marriage and allowing the honest criticism of religion by opposing the misuse of the blasphemy law.

- Jinnah was after a loose federal union, or consociationalism, which is about power sharing between communal groups in multinational states.

- Partition was inevitable, as Muslims would have remained in perpetual conflict in United India.

- Pakistan was a maximum demand, where the objective was to settle for autonomous regions and strong minority safeguards.

- Pakistan was not based on Hindu hatred or to establish Muslim rule, as Jinnah was the “protector general of the Hindus” and the “Muslim Gokhale”.

- Pakistan was a revolt against minority status, the idea was to end vertical division (with Hindu hegemony and Muslim subservience) by horizontal division for harmony.

- Pakistan was not about communalism of the masses, but about middle-class Muslim concerns on not being dominated in investment and commerce by the much superior hegemonic Hindu classes. In short, economic differences stood in way of the Hindu-Muslim unity.

- Jinnah invited young leftists to counterbalance the power of nawabs and landlords. He transformed the Muslim League from a party of nawabs and knights to an anti-imperialist struggle.

- Jinnah was from the middle-class, not the old aristocracy, unlike the nawabs and knights in the Muslim League. He was a secular and liberal role model compared to Gandhi and his village philosophy, the wealthy socialist Nehru, the stereotypical cleric Azad or Patel, who has been appropriated by the Hindu nationalists.

- Where Gandhi said, “I am a Hindu first and therefore a true Indian”, Jinnah pushed that, “I am an Indian first, second, and last”.

- Jinnah’s reference to Islam was qualified with democracy, equality, fair play, social justice, and brotherhood. His reference to Shariat was about personal law.

- Muslims needed Jinnah, not a staunch Muslim, as doctrinal differences were too great for an orthodox person to represent all the Muslims.

- Pakistan was opposed by the Muslim orthodoxy and the feudal lords of unionist party but supported by the Communist party and Ahmadis.

- Jinnah was not interested in pseudo-religious approaches, as he removed reference to God in his oath of office and cautioned against starting speeches with prayer. He viewed maulvis and maulanas as undesirables, just as he warned landlords and capitalists.

- Conservative Muslims like the Majlis Ahrar sided with the Congress and satyagraha. The likes of Maududi rejected Muslim nationalism as unlikely as a “chaste prostitute”, and the Kashmir struggle as unIslamic because of the involvement of the Ahmadi, Al Furqan brigade.

- The Jamaat Islami attacked the Muslim League for being too westernised and a bastion of Ahmadis.

- Jinnah favoured an independent and united Bengal in 1947 and agreed to the Suharwardy-Bose plan for an independent and united Bengal.

Pakistan was never meant to be an Islamic state but a haven for the Muslim minority of India that was joined by Dalits under Jogendra Nath Mandal.

The narrative that emerges from these 20 bullet points is clear. Pakistan was never meant to be an Islamic state but a haven for the Muslim minority of India that was joined by Dalits under Jogendra Nath Mandal. Jinnah’s own words stand as a testament on Ahmadis, the popular Pakistan slogan, Pakistani Hindus, and the state of Pakistan, as follows.

“What right have I to declare a person non-Muslim, when he claims to be a Muslim”.

“Neither I nor the Muslim League working committee ever passed a resolution – Pakistan ka matlab kya – you may have used it to catch a few votes”.

“We do not prescribe any schoolboy tests for their loyalty. We shall not say to any Hindu citizen of Pakistan, ‘if there was war would you shoot a Hindu?’”

“In any case Pakistan is not going to be a theocratic state – to be ruled by priests with a divine mission. We have many non-Muslims – Hindus, Christians, and Parsis – but they are all Pakistanis”.

My days of studying Pakistan Studies to write exams are long over. Though, I hope that the Pakistan narrative and curriculum builders invite Yasser Latif Hamdani and upcoming authors like Muhammad Umair Khan, to help them guide the newer generation of Pakistani students through their research, which can be disseminated through short five to ten minute videos. It is their voices that are much needed to honour Jinnah and the Pakistan movement. Lest we forget!