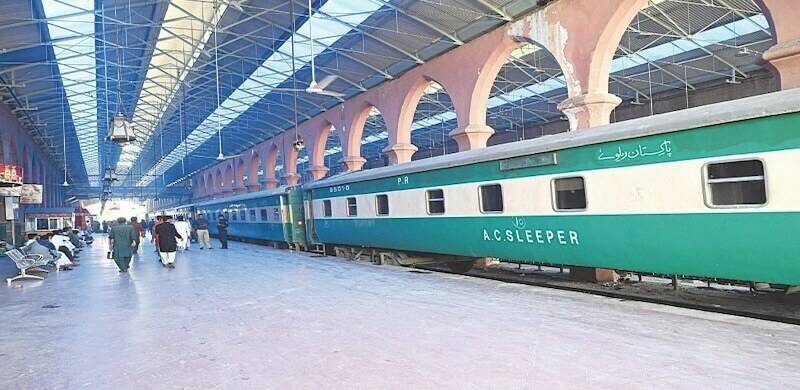

The recent rape of a woman by Railway staffers when she was travelling on a train from Multan to Karachi has generated a discussion about the safety provided to passengers using public transport. Some aspects linked to this issue merit serious attention.

Let me start with differentiating the difference between ‘sex’ and ‘gender’, as many who comment on such incidents are unaware of it. Sex refers to the biological attributes that one is born with, and what is used to define one as female, male or trans person. Gender refers to socially constructed norms, behaviours, attitudes, in line with prevalent power dynamics in a society, that influences expected roles and relationships from male, female or trans to the extent of being allowed.

The broader socio-cultural context, viewed from the lens of class, race, poverty level, ethnic group and age, not only complicates, but has different gender-based impact. This becomes the entry point of gender-based inequalities in terms of assigned/expected presence in public and private sphere; linked set of responsibilities; and opportunities to have access and control over rights, resources and decision-making for their lifestyle choices. Equality does not mean that women, men and trans become the same, but their access to rights, responsibilities and opportunities are not impacted by their biological sex and diversity is recognised.

Generally, one holds on to the ascribed sex at the time of birth; while gender ascription is evolving with societal progression, as its narrative of expectations change over time, in terms of how it envisions women, men and trans and functional relationship among them. Gender equality is not only an issue of human rights but a precondition for, and indicator of, people-centered development.

Sexual and Gender Based Violence (GBV), in Pakistan as well, has many forms that impact women, men and trans alike. It includes sexual violence, physical violence, emotional and psychological violence, harmful traditional practices and socio-economic violence. However, in majority of societies, its women and trans that face sexual harassment and violence in public spaces, which has expanded to online spaces as well. It becomes a fearful barrier for girls, women and their families that hampers their ability to claim their rights as an equal citizen; besides access to education, health, employment, control of economic resources and decision making. The extent of prevalence of violence is measured through Pakistan Demography and Health Survey (PDHS) 2017-18, that informs:

The superfluous concepts of honor and shame, associated with women and cloaked in harmful tradition and customs, expects them to let go of their choice and consent over life and endure in silence - be it a callous sexual remark or gesture; or forced and child marriage; or denial of inheritance; or rape as a threat to the act itself. Victim blaming and stereotyping is a curse and culling sword that is used by men in our society, sans any impunity, to express their misogyny and patriarchal control, irrespective of the fact that if one is related to or even knows the women to be judgmental. This starts with the choice of clothes to actually be out in a public space at any given time – irrespective of need or reason, and rather defines a good or bad girl/woman. This reduces women/girls’ freedom of movement and questions their safety at a public place.

Women do not have independence of movement as it needs to be authorised by a male head of household. In rural settings, mostly, women require an escort or companion as well – a male member of the household or an elderly woman. But in urban settings, it is a bit relaxed. The mobility for women in Pakistan is boxed on need basis - either social or economic, and is seen at times in defiance to religious-cultural factors. Non-availability to insecure public transportation is an issue for all. However, it impacts women and trans the most as it infringes and impacts their safety as they chose to step out of the house irrespective of their age, clothes or need and at any time of the hour.

The existing public transport system in Pakistan is limited and private transport is not affordable to a large segment of the society. Both have limited to no reserved seats for women. Public-transportation system in Pakistan does not meet the socio-cultural and financial needs of the people. The global research documents innumerable cases of harassment that women face in and around public spaces and public transports. The Delhi gang-rape case not only jolted India but brought attention to the similar issues faced by women in Pakistan.

In Pakistan, no woman feels completely safe while walking on the roads, waiting for a bus, taxi, train or plane -- from men on road to bus drivers, conductors and even fellow travellers. Harassment while waiting for or being on a public vehicle takes many forms like name calling, ogling, touching, groping and more recently, even rape. An Asian Development Bank (ADB) study states that women may not search for employment due to limited ability to commute safely, due to pervasive stigma, harassment, and/or violence on public transport or in the public space.

So, what should women do? The answer to this question is layered as it needs a societal response that accepts women to be in public space, on one hand; and a safe and functional public transport system, on the other. The latter needs state level time-based intervention, but the societal narrative can immediately be initiated by the political and governmental leadership. They need to inculcate safety and co-existence of women in public spaces. But unfortunately, misogyny and toxic masculinity continues to strengthen patriarchal controls on and around women. The gang rape of Mukhtaran Mai - authorised by the local Panchayat – was a a big question mark on the state of rule of law. Instead of taking action, the then President General Pervez Musharraf had suggested that women get themselves raped to get asylum abroad.

Since then, there has been no turning back on victim blaming for all forms of gender based violence. The Lahore motorway rape case shook women to the core. Instead of the focus being on ‘safety on road’ for women, CPO Lahore, Omar Saeed, questioned the character and the decision of women who chose to leave the house with her kids in the wee hours. The whole media splashed the comments and discussion got diverted from safety on road to why she was out of the house i.e. victim blaming.

After the recent rape of a woman who was travelling on a Bahuddin Zakriya train during her travel back from Multan to Karachi, Pakistan Railways CEO Farrukh Taimur Ghilzai said, “she was already in great troubles as she was first divorced by her husband; and was in distress by being disallowed by her in laws to meet her children” . Why should a CEO be talking about what her mental state instead of the heinous rape crime? Was it her mental state that attracted Pakistan railways staff to rape her?

What does the victim’s state of mind or condition have anything to do with the crime? For the last three days, social media has not stopped talking about why she was travelling alone. They are implying that she is a divorcee, so a bad woman. This is all it takes to divert attention and swing the narrative against the ‘character’ and choice of a woman to be out of the house and use public transport. The intensity of the crime is so easily overshadowed by things that don’t even matter.

Let me start with differentiating the difference between ‘sex’ and ‘gender’, as many who comment on such incidents are unaware of it. Sex refers to the biological attributes that one is born with, and what is used to define one as female, male or trans person. Gender refers to socially constructed norms, behaviours, attitudes, in line with prevalent power dynamics in a society, that influences expected roles and relationships from male, female or trans to the extent of being allowed.

The broader socio-cultural context, viewed from the lens of class, race, poverty level, ethnic group and age, not only complicates, but has different gender-based impact. This becomes the entry point of gender-based inequalities in terms of assigned/expected presence in public and private sphere; linked set of responsibilities; and opportunities to have access and control over rights, resources and decision-making for their lifestyle choices. Equality does not mean that women, men and trans become the same, but their access to rights, responsibilities and opportunities are not impacted by their biological sex and diversity is recognised.

Generally, one holds on to the ascribed sex at the time of birth; while gender ascription is evolving with societal progression, as its narrative of expectations change over time, in terms of how it envisions women, men and trans and functional relationship among them. Gender equality is not only an issue of human rights but a precondition for, and indicator of, people-centered development.

Sexual and Gender Based Violence (GBV), in Pakistan as well, has many forms that impact women, men and trans alike. It includes sexual violence, physical violence, emotional and psychological violence, harmful traditional practices and socio-economic violence. However, in majority of societies, its women and trans that face sexual harassment and violence in public spaces, which has expanded to online spaces as well. It becomes a fearful barrier for girls, women and their families that hampers their ability to claim their rights as an equal citizen; besides access to education, health, employment, control of economic resources and decision making. The extent of prevalence of violence is measured through Pakistan Demography and Health Survey (PDHS) 2017-18, that informs:

- Experience of violence: 28% of women age 15-49 have experienced physical violence since age 15, and 6% have experienced sexual violence. Seven percent of women who have ever been pregnant have experienced violence during pregnancy.

- ▪ Marital control: 8% of ever-married women report that their husbands display three or more specific types of controlling behaviours.

- ▪ Spousal violence: 34% of ever-married women have experienced spousal physical, sexual, or emotional violence. The most common type of spousal violence is emotional violence (26%), followed by physical violence (23%). Five percent of women have experienced spousal sexual violence.

- ▪ Injuries due to spousal violence: 26% of ever-married women who have experienced spousal physical or sexual violence have sustained injuries. Cuts and bruises are the most common types of injuries reported.

- ▪ Help seeking: 56% of women who have experienced any type of physical or sexual violence have not sought any help or talked with anyone about resisting or stopping the violence.

The superfluous concepts of honor and shame, associated with women and cloaked in harmful tradition and customs, expects them to let go of their choice and consent over life and endure in silence - be it a callous sexual remark or gesture; or forced and child marriage; or denial of inheritance; or rape as a threat to the act itself. Victim blaming and stereotyping is a curse and culling sword that is used by men in our society, sans any impunity, to express their misogyny and patriarchal control, irrespective of the fact that if one is related to or even knows the women to be judgmental. This starts with the choice of clothes to actually be out in a public space at any given time – irrespective of need or reason, and rather defines a good or bad girl/woman. This reduces women/girls’ freedom of movement and questions their safety at a public place.

Women do not have independence of movement as it needs to be authorised by a male head of household. In rural settings, mostly, women require an escort or companion as well – a male member of the household or an elderly woman. But in urban settings, it is a bit relaxed. The mobility for women in Pakistan is boxed on need basis - either social or economic, and is seen at times in defiance to religious-cultural factors. Non-availability to insecure public transportation is an issue for all. However, it impacts women and trans the most as it infringes and impacts their safety as they chose to step out of the house irrespective of their age, clothes or need and at any time of the hour.

The existing public transport system in Pakistan is limited and private transport is not affordable to a large segment of the society. Both have limited to no reserved seats for women. Public-transportation system in Pakistan does not meet the socio-cultural and financial needs of the people. The global research documents innumerable cases of harassment that women face in and around public spaces and public transports. The Delhi gang-rape case not only jolted India but brought attention to the similar issues faced by women in Pakistan.

In Pakistan, no woman feels completely safe while walking on the roads, waiting for a bus, taxi, train or plane -- from men on road to bus drivers, conductors and even fellow travellers. Harassment while waiting for or being on a public vehicle takes many forms like name calling, ogling, touching, groping and more recently, even rape. An Asian Development Bank (ADB) study states that women may not search for employment due to limited ability to commute safely, due to pervasive stigma, harassment, and/or violence on public transport or in the public space.

So, what should women do? The answer to this question is layered as it needs a societal response that accepts women to be in public space, on one hand; and a safe and functional public transport system, on the other. The latter needs state level time-based intervention, but the societal narrative can immediately be initiated by the political and governmental leadership. They need to inculcate safety and co-existence of women in public spaces. But unfortunately, misogyny and toxic masculinity continues to strengthen patriarchal controls on and around women. The gang rape of Mukhtaran Mai - authorised by the local Panchayat – was a a big question mark on the state of rule of law. Instead of taking action, the then President General Pervez Musharraf had suggested that women get themselves raped to get asylum abroad.

Since then, there has been no turning back on victim blaming for all forms of gender based violence. The Lahore motorway rape case shook women to the core. Instead of the focus being on ‘safety on road’ for women, CPO Lahore, Omar Saeed, questioned the character and the decision of women who chose to leave the house with her kids in the wee hours. The whole media splashed the comments and discussion got diverted from safety on road to why she was out of the house i.e. victim blaming.

After the recent rape of a woman who was travelling on a Bahuddin Zakriya train during her travel back from Multan to Karachi, Pakistan Railways CEO Farrukh Taimur Ghilzai said, “she was already in great troubles as she was first divorced by her husband; and was in distress by being disallowed by her in laws to meet her children” . Why should a CEO be talking about what her mental state instead of the heinous rape crime? Was it her mental state that attracted Pakistan railways staff to rape her?

What does the victim’s state of mind or condition have anything to do with the crime? For the last three days, social media has not stopped talking about why she was travelling alone. They are implying that she is a divorcee, so a bad woman. This is all it takes to divert attention and swing the narrative against the ‘character’ and choice of a woman to be out of the house and use public transport. The intensity of the crime is so easily overshadowed by things that don’t even matter.