Let us return to the early 19th century when leading theoreticians of that age, John Stuart Mill and Malcolm Macaulay & Co, were pondering predicaments arising out of the British Raj’s rule in India, which haunt us to this day: How does one go about educating the people of the Subcontinent? Its diversity of ‘races’, faiths, languages, values and cultures was perplexing. Between then and now, over a 200-year span, we have adapted to diversity. There are so many prefabricated perspectives to borrow from to reconstruct endless narratives. What rattled the English were the glaring differences between the English and the Subcontinental. They went beyond the vast blueness of Indian skies, the tranquility of its lakes and the golden languidness of its deserts, beyond the breathtakingly dense foliage with their colourful birds and strange night-sounds. The differences, it seemed, were existentially profound. Indeed, the notion of introducing mass English education to such a radically different Other, must have appeared quite ludicrous.

They were not to be deterred, though. It was not long before they began grappling with how to acculturate the natives to their own world-construct without attaching their deeply cherished ways. Calling them primitive right off the bat would be a mistake. Seeking to covertly dismantle their culture brick-by-brick was a remote possibility. It would be best to proceed with caution, by blending in and adopting native ways of learning.

This made the problem even worse: how does one inject the virus of a rapidly industrialising white culture into the bloodstream of dark, swarming natives bathed in mystical wisdom? And what of the Muslims who were languishing in remorse in the wake of their monumental collapse after 600 years of imperial dominance?

Rich tradition

So the colonials of the East India Company explored their options with compatriots who were by then, diving into native literature and books of Faith (Muslims, Hindus, Buddhists and Jains). Much consternation followed during and after their translations into English. They discovered that the tradition of meaningful, inquiry-oriented learning at extraordinarily complex levels of discourse went back many, many centuries, among Hindus, Buddhists and to an extent, Muslims. The storehouse of subcontinental knowledge gathered from translations filled them with awe. It also spurred their curiosity. So they foraged around the outskirts of subcontinental culture.

That’s when they discovered two compelling examples of learning which pleased them. The first: people recited the Holy Quran and other religious texts (the Bhagavad, Buddhist chants) without understanding them. The second: Persian poetry was recited more often than it was understood. W. D. Arnold, the director of Public Instruction in Punjab during 1857–58, described the concept of learning popular in Punjab at that time:

“We found a whole population agreed together that to read fluently and if possible to say by heart a series of Persian works of which the meaning was not understood by the vast

majority, and of which the meaning when understood was for the most part little calculated to edify the minority, constituted education.”

The regurgitation of lengthy passages or entire books was certainly an accomplishment of sorts. But the disconnect between learning and meaning-making appeared stark, as stark as the disassociation between their external and internal lives. It was difficult for the English to explain how such a deep and extensive body of subcontinental knowledge remained rationally disassociated with children’s education in madrasas and temples.

Be that as it may, the colonials were pleased with the disconnect for it would serve them well. The natives, they concluded, would accept a curriculum that had no relation to the child’s immediate environment, to his or her social and geographical specifics and daily practices. It would prove to be a “disassociation” that would leave a watermark on the modern colonial curriculum. It would never be erased. The mark has had a defining power and remains indelible to this day.

By 1854, Sir Charles Wood’s famous “Despatches” formalised education for the subcontinent’s natives. Its bureaucratic implementation can be distilled into five points: (1) a strict hierarchy controlling curriculum, syllabi, textbooks and teacher training; (2) acculturate native children in European attitudes and perceptions for this would prepare them to serve in middle and lower tiers of Britain’s colonial administration; (3) English would be the medium of instruction to foster such acculturation; (4) indigenous schools seeking government aid would have to conform to prescribed syllabus and textbooks; (5) promotion and scholarships would be subject to performance in “impersonal, centralised examinations”.

The goal of education was to culturally support the colonial policies of the East India Company. Since the colonials wanted to introduce machine-made goods from England to sell in the subcontinent, the training given in schools was mainly in unproductive skills e.g. writing extensive essays, learning the complexities of English grammar and etiquette, reading fairy tales and reciting musical nursery rhymes and songs that mostly went over everyone’s heads. The emphasis was on the natives outwardly assimilating colonial perceptions as extensively as possible. Most importantly, the English masters ensured they had complete control over their schools’ expansive delivery of European culture at every level in the hierarchy.

Pre-Colonial times

Before the advent of the colonials, teachers had enjoyed an elevated status in the subcontinent among followers of all faiths. They were the transmitters of knowledge, and the moulders of the “understanding heart, the seeing mind”. No one challenged their authority or autonomy in choosing appropriate texts, or in designing courses for their students. Often, they combined their priestly functions with teaching literacy skills in their own vernaculars. They taught skills useful to the village community.

However, all of that was brought to a swift end. According to Krishna Kumar, Director of the National Council of Educational Research and Training: “The new colonial system of education centralised official control, eroded the teacher’s autonomy by denying him any initiative in matters pertaining to the curriculum. It also imposed on the teacher the responsibility to fulfil official routines, such as maintenance of admission registers, daily diaries, record of expenditure, and test results.” Compared to the civil service, law or medicine, “school teaching meant a socially powerless, low-paid job… A substantial part of a school teacher’s daily routine consisted of fulfilling official requirements such as the maintenance of accurate records of admission, tests, and money.”

Failure to perform meant punishment (monetary cuts). It instilled a paralysing fear and even more timid behaviour among teachers who floundered at the bottom of the education hierarchy. For instance, in 1920, a teacher in the United Provinces earned Rs17 per month, a sub-deputy Inspector Rs70 per month and a Deputy Inspector Rs170 per month (that’s ten times more than a teacher). In Bombay, a primary level teacher earned Rs30 a month on average, but a Subordinate Education Officer earned Rs114 a month, and a Provincial Education Officer earned Rs486. The power and status was distributed accordingly. A teacher’s earnings for a lifetime could be threatened by a frowning Sub-Deputy Inspector who disapproved of a child’s behaviour during classroom inspection. It bred a culture of self-debasing sycophancy among teachers.

The pre-colonial system of reading mechanically, memorising by rote and regurgitating served as the perfect foundation for colonials to build upon. Textbooks became the most ubiquitous medium for seamlessly inserting and self-perpetuating rote learning. Colonial schooling imported this feature and mainstreamed it because it would help achieve the goal of social acculturation in new, novel ways.

Too much diversity

But to return to the immense and, to the colonialists, somewhat incurable diversity of the subcontinental people. The specifics were too many and too widespread to be incorporated for study within a narrow school curriculum. General information (or knowledge) was easier to accommodate. So there was a need to transcend regional and local specificities. It was easier to talk of common English farm animals than to talk of cows, buffaloes and goats. There were hidden significance attached to the association of meat for two major faiths. A textbook that identified or mentioned specific aspects of, say, Bengal (rivers and tigers) would have to do the same for Sindh (desert, camels), then Bihar, UP, Punjab… and so on. This was an unthinkably costly undertaking for textbooks. Far easier, and better from the acculturation perspective, to import them from England. Thus, dwelling upon British generalities (the attributes of animals, rivers and London Bridge, or the moon and stars, etc) produced obliquely banal questions that demanded reproducing dull facts, or abstract essay-type answers.

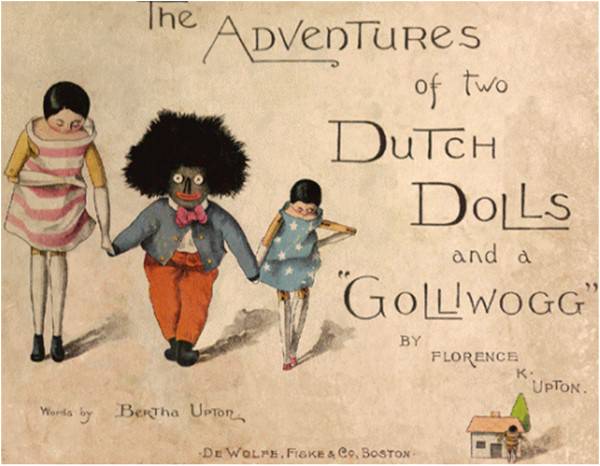

Paradoxically, since schooling was mainly about acculturation, not useful knowledge acquisition, the very elements of British culture found in their textbooks posed a serious problem: snowy barren winters and bursts of spring and flaring summers, family picnics, horse-riding in the glades, petting dogs in the living room, father sitting at the head of a table laden with odd, unrecognisable edibles, a half-naked fairy, a tall pig in a hat peeping through the door. To a bewildered native, such images and their corresponding texts would be incomprehensible. Many would regard it as either crazy or downright immoral. Words such as kettles, teapots, cottage fireplaces and Sunday dinners needed to be understood by a people who had no idea how they could be culturally conflated. One had to extract meaningful associations of mood, character and situations from within English contexts. No native teacher was capable of comprehending the many alien symbolisms embedded in texts, let alone making them comprehensible to his or her students.

The shortest route was to rote learn, commit entire texts to memory, regurgitate orally, then in writing. It was the simplest test of learning, and most useful because it served as solid evidence for grading answers to examination questions. Rote learning was encouraged and approved because it facilitated easy examining and assessment, both of which were centralised functions residing in the highest echelons of power.

Measuring success

Examinations and textbooks were key elements of central control. They served as turnstiles to opportunities for higher education and employment. The latter was reserved mainly for performing civil services in the colonial administration. But employment opportunities dwindled over time as they were filled. In order to avoid the passage of too many students going through the turnstiles, standards were constantly raised to reduce the numbers. Rising standards and scarcity of jobs was a double whammy that together caused an exponential rise in the fear of failing. Teachers, petrified about their own vocational failure, had to pre-empt failure among their students while also adhering to higher standards. It was quite a bind to be in.

The only way out of it was to ensure that teachers meticulously prepared their students for the examinations. All teaching was confined to the prescribed textbook which became the holy bible. The sacredness of the passages to be memorised depended on a careful consideration of what was expected in the exams. Often teachers passed on cues taken from hints dropped like bricks from above. Thanks to the powerful association between rote memorisation, learning and textbook, native student skills in committing vast amounts of printed English texts to memory would not have been possible.

Memorisation of passages was understood as a form of intellectual ingestion which penetrated (most mysteriously) the remote recesses of the learner’s cognitive system.

Kumar quotes Prakash Tandon (1857-1947), recalling how, in his grandfather’s days: “...the boys had coined a Punjabi expression, remembered even in our day, wishing that they could grind the texts into a pulp and extract knowledge out of them and drink it.”

The compulsory use of English as a medium of instruction in all subjects exacerbated matters. According to P. C. Ray, a famous Bengali scientist (1913): “A boy in an ordinary school from Class IV onward has to learn something of grammar, composition, phrases, idioms, homonyms, synonyms, difference between ‘shall’ and ‘will’, etc. Now for the matriculation course over and above these, he is expected to have mastered the contents of at least a dozen standard books.”

Annie Besant puts it succinctly: “the students were struggling to follow the language while they should have been grasping the facts.”

Evolution of exams

The written examination introduced by the British was used to centrally control all essential aspects of education: delivery by teachers, subject content, textbooks, classroom and administrative practices. Only those subjects were taught that could be tested via the written examination.

Long-winded essays written in flowing flowery English were the approved norm for English literature. Colonials were very likely amused by the quaintness of native English struggling to perfect the art of florid sentence construction. For the rest, students were expected to reproduce convoluted passages memorised by heart from textbooks. How else could a student’s written work confirm that textbooks had indeed been read? The word-by-word reproduction of the text was unerringly reliable and easy to mark.

The reproduction of passages in one’s own words was not allowed since it hardly mattered whether the words in the textbook had been understood. The task of simple regurgitation put in place a set of standardised norms. The most important one was that it spared the teacher from the worrying confusion of having to draw meaning from differently constructed English sentences. The colonial masters figured (quite rightly) that teachers lacked the linguistic competence or knowledge to judge student responses that used deviant vocabulary. When they did, it would be much easier for teachers to assume the students had not read their textbooks. They were failed. Even in the learning of Mathematics, students reproduced entire workings in problem-solving, from memory. They consisted of a teacher’s notes and workings faithfully copied from the board onto notebooks only to be regurgitated in exams.

Science

Subjects that could not be examined were excluded from the curriculum. Only those that could be taught via chalk-n-talk and tested via written exams could be taught in schools. This condition automatically excluded Science which required objective observations, lab experiments, the recording and reporting of facts and findings. In a sense, the lab environment could lay bare evident “truths” in the form of chemicals and elements combining and behaving in specific ways generic to them. Teachers could not deny the veracity of experimental results. If they did, then discussion and debate would follow and students would adopt defensive positions to support scientifically observed facts. Discussions could stray beyond the textbook into arguments and draw in other “extraneous” areas that could publicly threaten the authority of the teacher. Most significantly, the teaching of Science invited inquiry that intuitively discounted rote learning. The freedom of independent judgement threatened to sabotage the goal of colonial schooling.

The teaching of Science did not lend itself to long-winded exam essays that could be marked according to the teacher’s likes and dislikes. Indeed, the teaching of all vocational and practical skills remained unapproved in the curriculum for the same reason. They compromised the goal of acculturation of European culture upon subcontinental soil.

Mill and Macaulay argued over this. Mill supported Science education alongside European schooling but Macaulay opposed it and favoured only language-related subjects. In the end it was the latter’s supporters who won the day. A dense language-related teaching culture dominated the curriculum. Gifted and fluent English-speaking Muslims and Hindus who had drunk deep from the cup of acculturation found their way into the haloed halls of the colonial civil service.

By then, a deep and abiding antipathy towards Science had developed in the Subcontinent. Science symbolised colonial power and its dominance (new guns and ammunition) paved the way for colonialism. As the silent inner resistance among the natives, especially Muslims, grew, so did their distrust of Science as something evil. Many years later, when Science finally was get accepted into the curriculum, its importance in the classroom remained marginal. Lab work was almost absent. Teachers took on the mantle of authority, wielding a stick before a blackboard, explaining experiments with elaborate drawings, inviting no questions. As with other subjects, they were expected by their colonial masters to emphasise the authority of the textbook and the words of the teacher over and above all forms of rational thinking.

It is, therefore, not surprising that Science took longer than any other subject to gain popularity in Pakistan. Colonials regarded it with the same dread and distrust as their subject, albeit for very different reasons.

Any Pakistani reading this essay, may recognise the ghost in the educational system if they have been through its classrooms. Our curriculum rests and breathes in the dark shadows of a colonial era, unhinged, unchallenged and unchanged.

The writer is an Ed.M from Harvard University. He is a member of the National Association of Mathematics Advisors UK and has worked in Pakistan and Canada as well. He introduced Dyslexia and Math Learning Disabilities in Pakistan (1986) and set up the first Remedial Centre in Karachi, in 1987 (R.E.A.D.) @ShadMoarif

They were not to be deterred, though. It was not long before they began grappling with how to acculturate the natives to their own world-construct without attaching their deeply cherished ways. Calling them primitive right off the bat would be a mistake. Seeking to covertly dismantle their culture brick-by-brick was a remote possibility. It would be best to proceed with caution, by blending in and adopting native ways of learning.

This made the problem even worse: how does one inject the virus of a rapidly industrialising white culture into the bloodstream of dark, swarming natives bathed in mystical wisdom? And what of the Muslims who were languishing in remorse in the wake of their monumental collapse after 600 years of imperial dominance?

Since the colonials wanted to introduce machine-made goods from England to sell in the subcontinent, the training given in schools was mainly in unproductive skills e.g. writing extensive essays, learning the complexities of English grammar and etiquette, reading fairy tales that mostly went over everyone's heads

Rich tradition

So the colonials of the East India Company explored their options with compatriots who were by then, diving into native literature and books of Faith (Muslims, Hindus, Buddhists and Jains). Much consternation followed during and after their translations into English. They discovered that the tradition of meaningful, inquiry-oriented learning at extraordinarily complex levels of discourse went back many, many centuries, among Hindus, Buddhists and to an extent, Muslims. The storehouse of subcontinental knowledge gathered from translations filled them with awe. It also spurred their curiosity. So they foraged around the outskirts of subcontinental culture.

That’s when they discovered two compelling examples of learning which pleased them. The first: people recited the Holy Quran and other religious texts (the Bhagavad, Buddhist chants) without understanding them. The second: Persian poetry was recited more often than it was understood. W. D. Arnold, the director of Public Instruction in Punjab during 1857–58, described the concept of learning popular in Punjab at that time:

“We found a whole population agreed together that to read fluently and if possible to say by heart a series of Persian works of which the meaning was not understood by the vast

majority, and of which the meaning when understood was for the most part little calculated to edify the minority, constituted education.”

The regurgitation of lengthy passages or entire books was certainly an accomplishment of sorts. But the disconnect between learning and meaning-making appeared stark, as stark as the disassociation between their external and internal lives. It was difficult for the English to explain how such a deep and extensive body of subcontinental knowledge remained rationally disassociated with children’s education in madrasas and temples.

Be that as it may, the colonials were pleased with the disconnect for it would serve them well. The natives, they concluded, would accept a curriculum that had no relation to the child’s immediate environment, to his or her social and geographical specifics and daily practices. It would prove to be a “disassociation” that would leave a watermark on the modern colonial curriculum. It would never be erased. The mark has had a defining power and remains indelible to this day.

By 1854, Sir Charles Wood’s famous “Despatches” formalised education for the subcontinent’s natives. Its bureaucratic implementation can be distilled into five points: (1) a strict hierarchy controlling curriculum, syllabi, textbooks and teacher training; (2) acculturate native children in European attitudes and perceptions for this would prepare them to serve in middle and lower tiers of Britain’s colonial administration; (3) English would be the medium of instruction to foster such acculturation; (4) indigenous schools seeking government aid would have to conform to prescribed syllabus and textbooks; (5) promotion and scholarships would be subject to performance in “impersonal, centralised examinations”.

The goal of education was to culturally support the colonial policies of the East India Company. Since the colonials wanted to introduce machine-made goods from England to sell in the subcontinent, the training given in schools was mainly in unproductive skills e.g. writing extensive essays, learning the complexities of English grammar and etiquette, reading fairy tales and reciting musical nursery rhymes and songs that mostly went over everyone’s heads. The emphasis was on the natives outwardly assimilating colonial perceptions as extensively as possible. Most importantly, the English masters ensured they had complete control over their schools’ expansive delivery of European culture at every level in the hierarchy.

Failure to perform meant punishment (monetary cuts). It instilled a paralysing fear and even more timid behaviour among teachers who floundered at the bottom of the education hierarchy. For instance, in 1920, a teacher in the United Provinces earned Rs17 per month, a sub-deputy Inspector Rs70 per month and a Deputy Inspector Rs170 per month (that's ten times more than a teacher)

Pre-Colonial times

Before the advent of the colonials, teachers had enjoyed an elevated status in the subcontinent among followers of all faiths. They were the transmitters of knowledge, and the moulders of the “understanding heart, the seeing mind”. No one challenged their authority or autonomy in choosing appropriate texts, or in designing courses for their students. Often, they combined their priestly functions with teaching literacy skills in their own vernaculars. They taught skills useful to the village community.

However, all of that was brought to a swift end. According to Krishna Kumar, Director of the National Council of Educational Research and Training: “The new colonial system of education centralised official control, eroded the teacher’s autonomy by denying him any initiative in matters pertaining to the curriculum. It also imposed on the teacher the responsibility to fulfil official routines, such as maintenance of admission registers, daily diaries, record of expenditure, and test results.” Compared to the civil service, law or medicine, “school teaching meant a socially powerless, low-paid job… A substantial part of a school teacher’s daily routine consisted of fulfilling official requirements such as the maintenance of accurate records of admission, tests, and money.”

Failure to perform meant punishment (monetary cuts). It instilled a paralysing fear and even more timid behaviour among teachers who floundered at the bottom of the education hierarchy. For instance, in 1920, a teacher in the United Provinces earned Rs17 per month, a sub-deputy Inspector Rs70 per month and a Deputy Inspector Rs170 per month (that’s ten times more than a teacher). In Bombay, a primary level teacher earned Rs30 a month on average, but a Subordinate Education Officer earned Rs114 a month, and a Provincial Education Officer earned Rs486. The power and status was distributed accordingly. A teacher’s earnings for a lifetime could be threatened by a frowning Sub-Deputy Inspector who disapproved of a child’s behaviour during classroom inspection. It bred a culture of self-debasing sycophancy among teachers.

The pre-colonial system of reading mechanically, memorising by rote and regurgitating served as the perfect foundation for colonials to build upon. Textbooks became the most ubiquitous medium for seamlessly inserting and self-perpetuating rote learning. Colonial schooling imported this feature and mainstreamed it because it would help achieve the goal of social acculturation in new, novel ways.

Too much diversity

But to return to the immense and, to the colonialists, somewhat incurable diversity of the subcontinental people. The specifics were too many and too widespread to be incorporated for study within a narrow school curriculum. General information (or knowledge) was easier to accommodate. So there was a need to transcend regional and local specificities. It was easier to talk of common English farm animals than to talk of cows, buffaloes and goats. There were hidden significance attached to the association of meat for two major faiths. A textbook that identified or mentioned specific aspects of, say, Bengal (rivers and tigers) would have to do the same for Sindh (desert, camels), then Bihar, UP, Punjab… and so on. This was an unthinkably costly undertaking for textbooks. Far easier, and better from the acculturation perspective, to import them from England. Thus, dwelling upon British generalities (the attributes of animals, rivers and London Bridge, or the moon and stars, etc) produced obliquely banal questions that demanded reproducing dull facts, or abstract essay-type answers.

Paradoxically, since schooling was mainly about acculturation, not useful knowledge acquisition, the very elements of British culture found in their textbooks posed a serious problem: snowy barren winters and bursts of spring and flaring summers, family picnics, horse-riding in the glades, petting dogs in the living room, father sitting at the head of a table laden with odd, unrecognisable edibles, a half-naked fairy, a tall pig in a hat peeping through the door. To a bewildered native, such images and their corresponding texts would be incomprehensible. Many would regard it as either crazy or downright immoral. Words such as kettles, teapots, cottage fireplaces and Sunday dinners needed to be understood by a people who had no idea how they could be culturally conflated. One had to extract meaningful associations of mood, character and situations from within English contexts. No native teacher was capable of comprehending the many alien symbolisms embedded in texts, let alone making them comprehensible to his or her students.

The shortest route was to rote learn, commit entire texts to memory, regurgitate orally, then in writing. It was the simplest test of learning, and most useful because it served as solid evidence for grading answers to examination questions. Rote learning was encouraged and approved because it facilitated easy examining and assessment, both of which were centralised functions residing in the highest echelons of power.

Subjects that could not be examined were excluded from the curriculum. Only those that could be taught via chalk-n-talk and tested via written exams could be taught in schools. This condition automatically excluded Science which required objective observations

Measuring success

Examinations and textbooks were key elements of central control. They served as turnstiles to opportunities for higher education and employment. The latter was reserved mainly for performing civil services in the colonial administration. But employment opportunities dwindled over time as they were filled. In order to avoid the passage of too many students going through the turnstiles, standards were constantly raised to reduce the numbers. Rising standards and scarcity of jobs was a double whammy that together caused an exponential rise in the fear of failing. Teachers, petrified about their own vocational failure, had to pre-empt failure among their students while also adhering to higher standards. It was quite a bind to be in.

The only way out of it was to ensure that teachers meticulously prepared their students for the examinations. All teaching was confined to the prescribed textbook which became the holy bible. The sacredness of the passages to be memorised depended on a careful consideration of what was expected in the exams. Often teachers passed on cues taken from hints dropped like bricks from above. Thanks to the powerful association between rote memorisation, learning and textbook, native student skills in committing vast amounts of printed English texts to memory would not have been possible.

Memorisation of passages was understood as a form of intellectual ingestion which penetrated (most mysteriously) the remote recesses of the learner’s cognitive system.

Kumar quotes Prakash Tandon (1857-1947), recalling how, in his grandfather’s days: “...the boys had coined a Punjabi expression, remembered even in our day, wishing that they could grind the texts into a pulp and extract knowledge out of them and drink it.”

The compulsory use of English as a medium of instruction in all subjects exacerbated matters. According to P. C. Ray, a famous Bengali scientist (1913): “A boy in an ordinary school from Class IV onward has to learn something of grammar, composition, phrases, idioms, homonyms, synonyms, difference between ‘shall’ and ‘will’, etc. Now for the matriculation course over and above these, he is expected to have mastered the contents of at least a dozen standard books.”

Annie Besant puts it succinctly: “the students were struggling to follow the language while they should have been grasping the facts.”

Evolution of exams

The written examination introduced by the British was used to centrally control all essential aspects of education: delivery by teachers, subject content, textbooks, classroom and administrative practices. Only those subjects were taught that could be tested via the written examination.

Long-winded essays written in flowing flowery English were the approved norm for English literature. Colonials were very likely amused by the quaintness of native English struggling to perfect the art of florid sentence construction. For the rest, students were expected to reproduce convoluted passages memorised by heart from textbooks. How else could a student’s written work confirm that textbooks had indeed been read? The word-by-word reproduction of the text was unerringly reliable and easy to mark.

The reproduction of passages in one’s own words was not allowed since it hardly mattered whether the words in the textbook had been understood. The task of simple regurgitation put in place a set of standardised norms. The most important one was that it spared the teacher from the worrying confusion of having to draw meaning from differently constructed English sentences. The colonial masters figured (quite rightly) that teachers lacked the linguistic competence or knowledge to judge student responses that used deviant vocabulary. When they did, it would be much easier for teachers to assume the students had not read their textbooks. They were failed. Even in the learning of Mathematics, students reproduced entire workings in problem-solving, from memory. They consisted of a teacher’s notes and workings faithfully copied from the board onto notebooks only to be regurgitated in exams.

Science

Subjects that could not be examined were excluded from the curriculum. Only those that could be taught via chalk-n-talk and tested via written exams could be taught in schools. This condition automatically excluded Science which required objective observations, lab experiments, the recording and reporting of facts and findings. In a sense, the lab environment could lay bare evident “truths” in the form of chemicals and elements combining and behaving in specific ways generic to them. Teachers could not deny the veracity of experimental results. If they did, then discussion and debate would follow and students would adopt defensive positions to support scientifically observed facts. Discussions could stray beyond the textbook into arguments and draw in other “extraneous” areas that could publicly threaten the authority of the teacher. Most significantly, the teaching of Science invited inquiry that intuitively discounted rote learning. The freedom of independent judgement threatened to sabotage the goal of colonial schooling.

The teaching of Science did not lend itself to long-winded exam essays that could be marked according to the teacher’s likes and dislikes. Indeed, the teaching of all vocational and practical skills remained unapproved in the curriculum for the same reason. They compromised the goal of acculturation of European culture upon subcontinental soil.

Mill and Macaulay argued over this. Mill supported Science education alongside European schooling but Macaulay opposed it and favoured only language-related subjects. In the end it was the latter’s supporters who won the day. A dense language-related teaching culture dominated the curriculum. Gifted and fluent English-speaking Muslims and Hindus who had drunk deep from the cup of acculturation found their way into the haloed halls of the colonial civil service.

By then, a deep and abiding antipathy towards Science had developed in the Subcontinent. Science symbolised colonial power and its dominance (new guns and ammunition) paved the way for colonialism. As the silent inner resistance among the natives, especially Muslims, grew, so did their distrust of Science as something evil. Many years later, when Science finally was get accepted into the curriculum, its importance in the classroom remained marginal. Lab work was almost absent. Teachers took on the mantle of authority, wielding a stick before a blackboard, explaining experiments with elaborate drawings, inviting no questions. As with other subjects, they were expected by their colonial masters to emphasise the authority of the textbook and the words of the teacher over and above all forms of rational thinking.

It is, therefore, not surprising that Science took longer than any other subject to gain popularity in Pakistan. Colonials regarded it with the same dread and distrust as their subject, albeit for very different reasons.

Any Pakistani reading this essay, may recognise the ghost in the educational system if they have been through its classrooms. Our curriculum rests and breathes in the dark shadows of a colonial era, unhinged, unchallenged and unchanged.

The writer is an Ed.M from Harvard University. He is a member of the National Association of Mathematics Advisors UK and has worked in Pakistan and Canada as well. He introduced Dyslexia and Math Learning Disabilities in Pakistan (1986) and set up the first Remedial Centre in Karachi, in 1987 (R.E.A.D.) @ShadMoarif