A cursory glance at the ramifications of COVID19 starkly reveals how it has strengthened systemic and structural inequalities when it comes to gender, race, religion, ethnicity, political status and wealth.

Similar to the evolving nature of the virus itself, implications of the pandemic have long moved from ‘physio-social’ to one that is psycho-social and political. Equipped with vitriolic nomenclatures such as the Chinese virus and Corona jihad, the contagion has led to a further dehumanization of the marginalized and vulnerable; further emasculating COVID19 response efforts all over the world including the South Asian region.

Fueling Hate With Fear

During the first quarter of 2020, thousands of Shia pilgrims from not just the Sub-continent, but also from Oman, Qatar, Yemen and Bahrain travelled to Iran. With the first two cases detected in the Southern port city and megapolis – Karachi, Pakistan; some 2000+ returning pilgrims were moved to institutional quarantine centers in their home cities while about 2800 were received at the Taftan border. Fear mixed with prejudice consumed the majority of the population enough to allege that the virus had infiltrated the country through the pilgrims returning from Iran. A Pakistani daily revealed: “The pilgrims remained in quarantine for a minimum of 28 days and were allowed home only after they tested negative for Covid19.”

According to a report published by the Islamabad Policy Institute (IPI), ‘Covid19 in Pakistan The Politics of Scapegoating Zaireen’ (pilgrims) stated: “In some instances, the pilgrims remained in quarantine for up to 50 days. Therefore, the pilgrims cannot be responsible for local transmission.”

The report further asserted: “Profound political polarization, deep sectarian schisms, and anti-Iran sentiments in the country made the controversy murkier. The government's messaging on the pilgrims' crisis was particularly found wanting. Instead of transparently explaining the issue and addressing misconceptions and tackling deliberately propagated disinformation, the government chose buck-passing because of political compulsions. Contradictions and discrepancies were also noticeable in the government's messaging.”

In the neighboring India, situation was also grave, with the Tableeghi Jamaat – an Islamic group, accused of spreading the coronavirus after it held its annual congregation in local New Delhi mosque. Over 2000 Muslims had travelled to India for religious activities since January 1, 2020. Over 3300 Tableeghi Jamaat members were then put under institutionalized quarantine for almost 40 days. On May 6th, 2020, the government ordered the release of individuals who had completed the mandatory quarantine and showed no signs of the virus.

It is certainly not untrue to claim that the increasing polarization across the Sub-continent has led to an obtrusive religiosity as well as fascist extremism. The repercussions that resulted due to the negligence and ignorance of the Tableeghi Jamaat in India which was staunchly criticized by other Muslims or the deliberate propagation of disinformation in Pakistan led to a corrosive messaging that vilified as well as criminalized communities as a whole in the respective countries.

Statelessness, Gender & Inequities in Healthcare

The devastating plight of the refugees in Bangladesh, Indonesia and Malaysia – among other countries - adds yet another debilitating layer to the raging crisis. On June 15th, 2021, Human Rights Watch reported that the United Nations refugee agency (UNHCR) had not only improperly collected personal information as well as shared it with the government without informed consent from ethnic Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh, the latter then shared that data with Mynamar “to verify people for possible repatriation.”

The UNHCR denied any wrongdoing, stating it had obtained consent as well as explained all purposes.

More recently, on June 30th, the country again came into the Human Rights Watch focus as it reported Rohingya refugees facing medical crisis after nearly 18000 refugees were sent to the silt island of Bhasen Char as a solution to the overcrowding of Cox Bazaar where a million Rohingyas reside. While the medical plight of refugees at Bahsen Chat can be attributed to the overwhelming of an already inadequate healthcare system on the island, their marginalization is deeply rooted to their statelessness. A refugee’s dignity, respect and their basic human rights are already comprised especially in Bangladesh, India and Pakistan as all the three countries have yet to ratify the prevailing international laws protecting refugees or the 1951 UN Refugee Convention.

According to Health and Human Rights Journal: “It is a particularly challenging status during a global pandemic such as COVID-19, when hostility toward outsiders is exacerbated, the availability of essential humanitarian services is compromised, and an informal labor market generating subsistence income is brought to a halt.”

Although the constitution in almost every country in South Asia safeguards and protects state citizens, which includes people belonging to both religious majority and minorities; realities are ominously different. And it becomes equally if not more incapacitating for vulnerable groups when gender is also thrown in the mix.

Many women in rural Pakistan especially remain undocumented, meaning they do not possess national identification card. While the country rolled out its computerized national identification card (CNIC) initiative as early as year 2000 – each government has had its share of challenges in bringing women into the digital ID fold. According to a report published by the Punjab Commission on Status of Women in 2019, in rural areas of Punjab, 56 percent of young women have CNICs. As compared with their rural counterparts, urban women have 64 percent of CNICs of women age 18 years and above. Fewer CNICs were issued to women in Punjab (41 percent) as compared to men (59 percent).” Posing a threat not just to their potential status as a citizen of the state, remaining undocumented means they fall under the radar of the vaccination initiatives.

Thousands of miles away, foreign students, refugees, members of marginalized communities, irregular and/or undocumented migrants in Malaysia are also facing challenges accessing vaccines. While the government has been very vocal about vaccine equity internationally, many people from the said communities as well as stateless individuals without a Malaysian identity card or passport fail to get vaccinated. Many including members of indigenous communities have actually been turned away for not possessing proper documents.

In Pakistan, lawyers and rights advocates believe women remaining undocumented keeps their enablement in check as far as their bodily, health and financial autonomies are concerned. Without state identity, women cannot exercise their rights as state citizens and neither can they be protected through state laws. Same holds true for the plight of those marginalized in Malaysia with an added layer of the fear of deportation and arrests. In both cases, vulnerabilities stem from being robbed of their basic human rights and access to vaccines; putting not just one but entire populations in harm’s way.

In the Shadows of the Pandemic

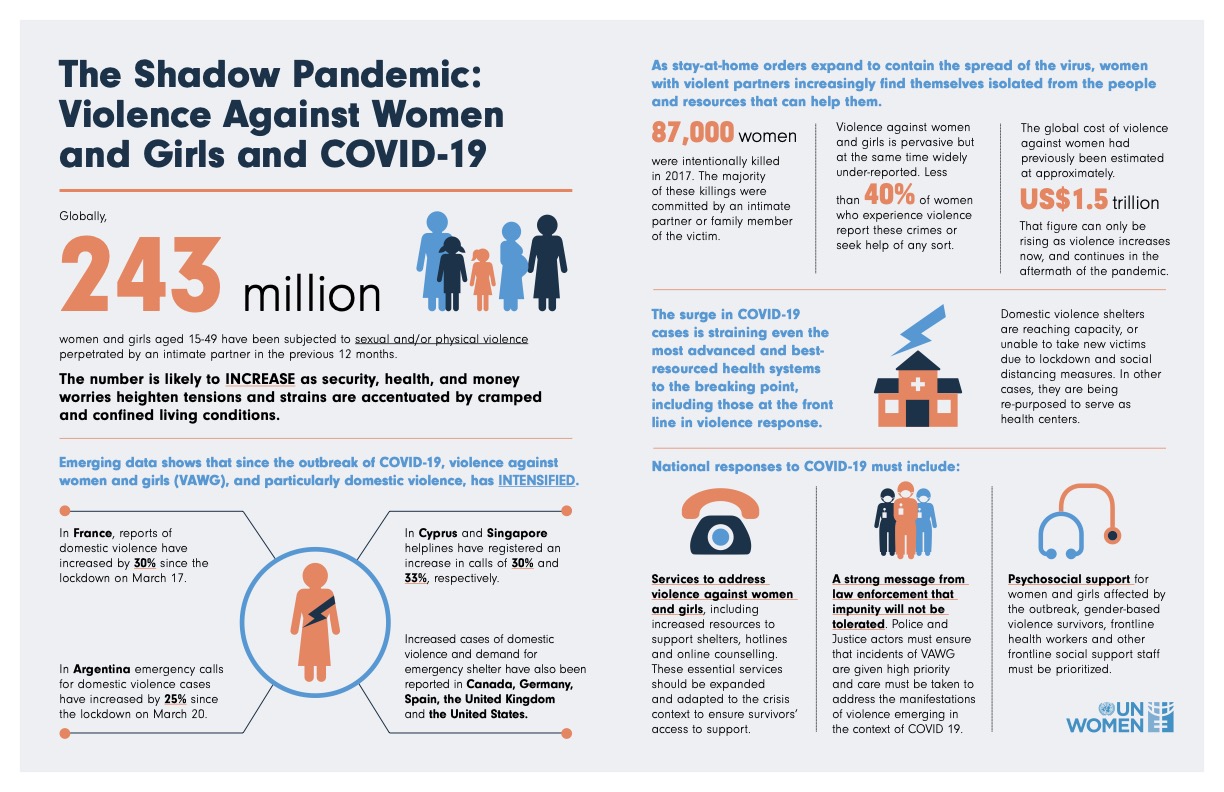

Gender-based violence is one of the gravest human rights violations – a pandemic afflicting the entire globe from time immemorial. The rise of the super bug has magnified and worsened an already challenging situation. Pre-COVID, 1 in 3 women experienced at least some form of violence. And with lockdowns and social distancing in place during the first and second waves, the situation has only deteriorated further.

While data gathered by helplines in many countries, including Digital Rights Foundation Pakistan’s Cyber Harassment Helpline, have shown a sharp increase in violence related calls, UN Women reports a diversion of resources and efforts from gender-based violence to urgent COVID19 relief.

In a bid to curb the contagion, the world moved towards staying home to stay safe. This made the most vulnerable come in close as well as constant contact with perpetrators of violence. Remaining in isolation without access or reach to different forms of help and support created an enabling environment for the perpetrator as victims are less likely to be in contact with family and friends during lockdowns and social distancing. The situation becomes all the more harmful as women’s mental health takes a sharp nosedive as the fear of violence escalates, reports a UN Women brief.

According to one report, the number of domestic violence cases reported to a police station in Jingzhou, a city in Hubei Province China, tripled in February 2020, compared to the same period the previous year.

Almost 30 percent of the respondents in a survey said that they have experienced some form of gender-based violence which includes stigma and discrimination. The said survey was conducted in June 2020 by the International Community Women Living with HIV in Asia and the Pacific (ICWAP) with support from the UNAIDS Regional Support Team for Asia and the Pacific.

According to a report released by the National Commission on Violence against Women, even the official numbers of reported cases of violence against women living with HIV has increased considerably during the pandemic. Nepalese women living with HIV are reportedly facing similar sufferings as a consequence of the pandemic. Sara Thapa Magar, the President of the National Federation of Women Living with HIV and AIDS (NFWLHA), Nepal, reflects on Lily’s (not her real name) story, a woman living with HIV who was beaten by her husband after she went to the local hospital to get refills of her antiretroviral therapy. The current circumstances, including limitations on access to helplines and disrupted public services, have made reporting of abuse and violence even harder, reports UNAIDS.

It truly is no rocket science to understand that any kind of crisis affects men and women differently and only compounds already existing inequalities and risk for the more vulnerable. Social protection system either does not exist or is almost non-existent across countries in the Global South and by extension South Asia. Risk mitigation and redressal is possible through not just a multi-stakeholder, rights-based approach; it needs representation in policy-making and laws so that proper implementation can be carried out organically. But more than that, weeding out the root cause is no simple effort. It starts with unshackling mindset from deeply entrenched feudalistic belief system fueled by power. Indeed, humanity is in for a long haul and it really starts by working together!

Response, Relief & Respite

COVID-19 is more than just a virus; it is a manifestation of an ailing society. Relief is only conceivable through appropriate response. Respite is only possible when pathways to response are created through a rights-based, multi-stakeholder and humanitarian approach.

The people and NOT race, religions or ethnicities of India came together on social media for immediate response to distress, be it locating oxygen cylinders, getting help find food for a family, donating artwork to charity for the much needed COVID related funds or simply lending a voice of support.

Mainstream media has a huge responsibility to build a conversation leading towards redressal and mitigation of crises; instead of propagating dis-info, use of bad science and vitriolic messaging inciting hate and fear especially of the marginalized and the vulnerable. Mainstream media needs to work for the people instead of an agenda; it needs to do better – much better!

Instead of passing buck or diluting focus, the powers that be in countries across South Asia need to address crises by assessing and designing both short and long term roadmap to relief. This can only be done through multi-stakeholder engagement with actors representing all segments of society. Unless the underlying challenges of the pandemic are not mitigated, the scale of socio-economic and humanitarian devastation will remain staggering.

Curing humanity of this affliction starts with humankind coming together. Physical walls and borders are still easy to dismantle when compared with walls of hate, prejudice and intolerance that lie deep within.

Voices of Resilience

Kousalya Periasamy, the founder of the Positive Women Network (PWN+), explains the multiple impacts of COVID-19 on the life of women living with HIV in India. “Many women and girls were afraid of going to the hospital to get their antiretroviral therapy refill and access general health services out of fear of COVID-19,” said Periasamy. “Women living with HIV who had COVID-19 were not able to provide for and look after children if they had to be admitted into the hospital.” Given the need to communicate with local network partners and members, PWN+ established a WhatsApp group to ensure that women living with HIV had access to reliable information on HIV and COVID-19. PWN+ also mobilized support from different local organizations to donate food and supplies and handed out pamphlets containing HIV and COVID-19 information.

– UNAIDS Press Release/Relief Web

We don’t have much data available as far as members of the transgender community is concerned, even during the time of the pandemic. I don’t think it’s really because of any bias or conflict in society. I think it has more to do with access and awareness. Most of them are not even aware of health-tech entities like Sehat Kahani or they don’t have access to it.”

Dr. Sara Saeed Khurram – health innovator, Co-founder and CEO of award winning Sehat Kahani (an all-female health provider network that offers quality healthcare in Pakistan to those in need using telemedicine)

“There has been a heightened persecution since the beginning of the first lockdown of the (Ahmadi) community in many ways. But I am not sure how closely it is linked with COVID. Stuff like increasing attacks on Ahmadi places of worship or desecration of Ahmadi graves. Things have been happening for so long and it has gradually started to worsen. One thing we have noticed is the increase in online hate, especially during the first few months of the pandemic. How we see that is through the assumption that because people are spending more time online, you see the extra level of aggression that already exists in the real world. You see it transitioning itself in online spaces. In terms of COVID related stuff, I think for the most part, it has been ok. There hasn’t been many problems in terms of vaccinations etc. so far. And in terms of dividing them on gender lines, I don’t think it has been massive for Ahmadis or any other minority community in terms of persecution or hostility linked with COVID. I just feel there is a hostility in Pakistani society against minority groups which is just carrying on. One noticeable difference which may be related to the pandemic is the greater levels of hate in online spaces.”

“In Pakistan, religious harmony means so much social harmony. Religion is so all-encompassing and I feel that it is so frayed now, there’s so much tension around it.. It is such a combustible situation that at any moment of acute difficulty like the pandemic will lead to the fraying of that religious compact – making things difficult for the more vulnerable communities so whether its covid or anything else I just feel that the trajectory that Pakistani society is on and all the social norms and values that society has come to accept make this a fertile ground for any kind of religious tension to bubble up whenever there is acute kind of problem in the country or any kind of national crisis. And I feel that that’s just the way we are now and COVID has been just a symptom of that as opposed to being the driving force.”

Member of the Ahmadi Community – Pakistan

From March 28 to June 10, 2020, we received 11 cases of forced marriages. Proper mechanisms to address domestic violence by the government is still lacking. The existing Dar ul Amans are already overcrowded and these Dar ul Aman are not entertaining more cases due to the COVID 19. Further the required support from police and family courts is also limited during COVID 19.

However, there is a helpline from Punjab Commission on the Status of Women (PCSW) and Human Rights Commission of Pakistan for counseling and legal aid. But there is no system/arrangements of shelter for survivors of violence as per need they have to live with the abuser under the same roof.

Bedari – Pakistani NGO

The COVID-19 pandemic has laid bare the social inequalities that have been constantly exacerbated through the use of patriarchal, privilege-centric, and power-driven policymaking at all levels. World over, the lockdowns have been challenging in many, many difficult ways. Among those that are struggling with the weight of having to stay home are those that are facing domestic violence. We're talking about staying home to stay safe - but they're not safe because they're staying home. Women have faced violence across the board: to the point that a woman who recently reached out said that she had been beaten because she tested positive. Reporting a crime and calling for help is not easy in regular times: the decision to stay or to leave, the questions of having to address the stigma, the challenges of moving away, financial independence, and not having anywhere to go are only just a few of the many challenges that survivors are forced to confront. The system is also overloaded: which means that there are fewer police officers, few shelters available, few liaisons who can support survivors, and few to no means to get around town in search of safety. Bearing this time with toxic people, violent people, and abusive people is unbearable, to say the least. The non-designation of support services for survivors of GBV as essential continues to remain a challenge, as more and more women and non-binary people are left to their own defences.

Kirthi Jayakumar – Founder The Gender Security Project

DRF's Cyber Harassment Helpline receives complaints from all over Pakistan regarding online harassment and threats, however, with due respect to the individuals calling us, we do not ask them for their religious affiliations or beliefs, unless they mention it themselves, therefore our team is unable to compile precise numbers as to how many women from religious minority groups are affected by cyber harassment.

We have to remember that there is reluctance in minority communities in general when it comes to reporting cybercrime and harassment, given how our society treats members of this community and given how laws and state narratives are built around them.

IRADA released a study in 2019 about religious communities in Pakistan and how they feel about online spaces. All the participants they spoke to revealed that they had experienced online trolling and online attacks. Combine this finding with the fact that DRF noticed a massive spike in cyber harassment cases during the initial months of the pandemic, which sustained throughout the year, and you can begin to see a trend, which allows us to predict that women from religious minorities faced more cyber harassment and threats than the amount of online hate and vitriol they see on a day to day basis.

Digital Rights Foundation Pakistan (DRF)

Speaking to the current and general state of oppression, the pandemic definitely added fuel to the fire. The lockdowns forced more people to operate online for their everyday tasks, making everyone more susceptible to online harassment and violence, however, the effect of this fell disproportionately on women than men.

The issue in Pakistan is there is no implementation of the laws meant to protect against cybercrimes. The LEAs in charge of this part of the law are understaffed, underfunded and not trained in the intricacies of dealing with such cases. From issues of victim blaming to insensitivity towards victims, complainants find themselves having to fight for themselves and fend for their own protections.

When it comes to all kinds of oppression and violence against women perpetuated in this country and how to rectify this issue, we need to realize that Pakistan needs to critically look at its policies and how to implement them. Often we make policies without a roadmap on how to implement them and more importantly how to implement them in a way that is beneficial for all people. For example, with the current Prevention of Electronic Crimes Act, the FIA's Cyber Crime Wing was established, which was a great step in the right direction, however, it was also equally important for there to have been planning on how to sensitize the officers there to deal with complainants.

Nighat Dad – Founder Digital Rights Foundation Pakistan

If you look at the constitution of Pakistan, it clearly states equality for all. But if you look further, there actually is no policy framework, no personal laws for Hindus or Sikhs.

There is a dual attitude as far as the state is concerned. Be it the majority or the state, they think this country is only for Muslims. That is the mindset. There is a duality in attitude, one focuses on national politics and the other international. Minorities do not exist in national life because diversity is not accepted. I feel the state is not serious about minorities. Diversity has successfully been eroded.

There have been quite a few challenges. There have been many state led ration distribution drives but for some reason, minorities were left out. However, a few charity organizations and specifically Al Khidmat made sure to deliver.

I think it is the intersectionality of one’s socio-economic status and religion that makes one vulnerable. We can note this even in the attitude of the state when it comes to superior caste Hindus in the country and Dalits, bearing in mind, we do not believe in caste system.

Essential workers were laid off without any compensation. In addition to this, no attention was really given to essential workers. There was a lot of talk about PPEs for doctors and we came forward and started a national call for the safety and protection of sanitation workers, demanding them to be included as frontline workers.

Moreover, these sanitation workers also worked as support staff at various hospital’s quarantine wards. And as you know most of these sanitation workers are Christians. They are not trained and worked without proper PPEs inside the wards. It is like you want the most vulnerable to fight the pandemic.

While Pakistani Christians make up about 2 percent of the population, data reveals that they account for more than 75 to 80 percent of sanitation workers.

There has definitely been a surge in cases of forced conversions or maybe the cases were not previously reported as they are now. There has indeed been a noticeable rise in certain districts of interior Sindh and central Punjab.

I am not sure if this is directly linked with COVID but there have been cases in cities of Hyderabad, Faisalabad and Lahore where Christian nurses were accused of blasphemy. What is surprising is that these cases occurred just a few months apart. The situation had turned grave as their fellow staff members actually wanted to kill them and the police had to intervene.

Mary James Gill Politician, Human Rights Lawyer & Advocate, Pakistan

Saira Masih was heavily pregnant when her husband Sonny called from work on 21 March. He was being sent to work in a quarantine centre for 156 Muslim Shi’ite pilgrims who’d returned home to Pakistan from a pilgrimage to Iran, already a coronavirus hotspot. He said he would be home in two weeks. The centre, set up by the district Faisalabad government, was staffed by medics, police, civil defence officials and at least six sanitation workers – to clean it. The six shared the surname Masih (from ‘Messiah’) identifying them as Pakistani Christians.

Firdaus, mother of Shakoor, another of the six, takes up the story: “First, they were told they could leave soon after cleaning the centre. But they were tricked into going in there. They ended up being in the centre 24 hours a day for almost a month, bringing food, medicine, soap and shampoo and even making the beds”.

This was because no-else would go close to those quarantined, including the police guarding them. Even the doctor monitoring them would keep his distance.

Excerpt from Unprotected, unpaid or unrecognized: Christian workers on the frontline in Pakistan’s fight against Covid-19 – Written by Asif Aqeel / Institute of Development Studies

“We have been travelling to Iran for more than 10 years now and never imagined something like this could happen to us. We were stuck in Iran for more than two months. Our own government wasn’t letting us in. We reached out to anyone and everyone who could help. We pleaded on social media, any place that could hear our cries of help but at that point, everything seemed futile. There was fear and panic everywhere. We couldn’t fly back to our own country, our home! We made so many requests. Our funds were depleting fast and more than half of our group consisted of people over 50. We were running out of our medicine supplies as well. It was horrible.”

Fatima - Member of a Shia community in Karachi, Pakistan

“We contracted COVID19 during the first wave. The fear of the disease was not as much as that of being ostracized. We were also afraid of being administered wrong medicines. Such was the magnitude of our distress and anxiety.”

Shahnaz from Bhopal India

________________

Sabin Muzaffar is the Founder and Executive Editor Anankemag.com and Ananke Women in Literature Foundation (www.anankewlf.com). A self-proclaimed intersectional humanist, her work focuses on inclusion, gender and development in the Global South. Twitter: @critoe