Amidst an on-going debate on the Single National Curriculum (SNC), an important and highly relevant research report, titled, Lessons from the Nationalisation of Education in 1972 has been published by the Lahore-based Centre for Social Justice. Impressively researched and intellectually provocative, the report convincingly argues that the nationalization of Church-run schools in 1972 economically impoverished an already marginalized Christian community besides alienating it politically and culturally.

With an incisive preface by Dr Yaqoob Bangash, the report consists of two chapters: Peter Jacob’s chapter analyses the impacts of nationalization on the lives of Christian community while Dr Tahir Kamran foregrounds the consequences of nationalization on the quality of education.

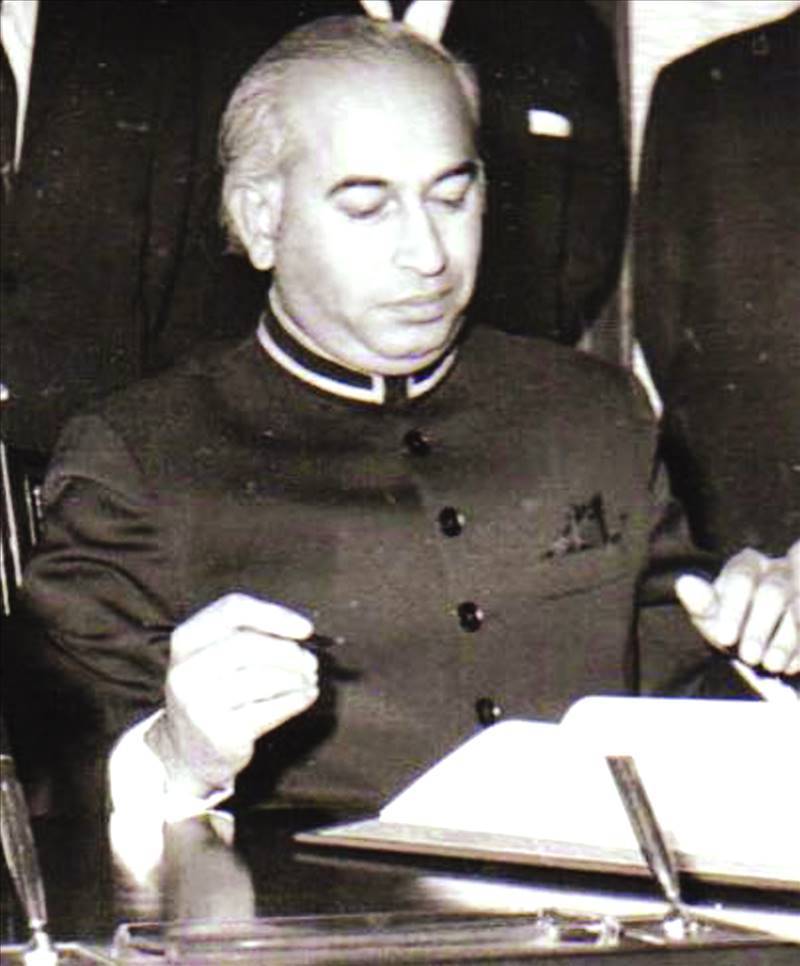

Under Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto’s leadership, 3,334 institutions were nationalized on March 15, 1972. Nationalized institutions included 1,826 schools, 346 madrassas, 155 colleges and five technical institutes. 118 of them were church-run institutions.

Though missionary schools/colleges constituted a small portion of the overall drive yet they had terrible consequences for Christians.

Let us begin with the economic fallout for the Christians in the country. These schools offered job opportunities to a community otherwise marginalized in the job market. Likewise, it proved to be a big blow to literacy rates among the Christians.

By 2019, the share of Christian teachers in the former missionary schools had dropped to 9 percent while the Christian students constituted only 16 percent in these schools. Likewise, the loss of these schools also meant a loss of income for the church, let alone their formidable soft power.

Secondly, an important avenue to forge inter-religious harmony was lost since many middle-class families would send their children to missionary schools since these quality-education schools were not as expensive as the privately-run schools. Simultaneously, discriminations faced by the Christian students at public schools, especially on the countryside, furthered Christians’ ghettoization.

Thirdly, as Dr Kamran points out, the state-takeover of the missionary schools was against the spirit of nationalization. Since nationalization was aimed at providing access to quality education, to all and sundry, by ending a system of for-profit schools. The schools run by the church were neither commercial nor elite.

Lastly, such is the logic of the Islamified schooling system (and the society in general) that the Christian students have to opt for Islamiat instead of Ethics. The following figures suggest the cruel exclusion of Christian students: In 2018, 0.07 percent of the Christian students studied Ethics at Grade 5 level, 0.06 percent at the Grade 8 level. Likewise, 80 percent (out of 15,917 students) opted for Islamiat in the matriculation years. At Intermediate level (out of 7,405), 1.7 percent studied Ethics, 8.8 percent Civics while 90 percent ‘opted’ Islamiat.

“While attacking the self-respect and identity of religious community might not have been the primary aim of the 1972 nationalisation…this action did severely undermine Christian’s confidence in Pakistan,” Dr Bangash observes.

The Christian community understood the colossal loss Bhutto was inflicting on the community. Hence, they started agitating. The agitation took a tragic turn when a 2,000-strong peaceful demo in Rawalpindi, on 30 August 1972, was brutalized by the police. Three demonstrators: R. M. James, Nawaz Massih and an unidentified person, were shot dead while another 25 were injured. Over a dozen were also arrested.

Ironically, Bhutto was elected from a Lahore constituency with over 70,000 Christian residents. Without Christian votes, he would not have won in Lahore. He vacated the seat because he wanted to retain his Larkana seat. In his place, Mehmood Qasori was elected as the PPP candidate in the by-election. Hence, Christians were double betrayed because Bhutto had also presented himself as a champion of the subaltern.

The entire report justifiably is an indictment of Bhutto’s opportunistic politics. For instance, while 118 Urdu-medium Christian schools were nationalized, the elite schools meant for the gentry were exempted. Bhutto also inducted Kausar Niazi, a maverick mullah, in his cabinet which further alienated the Christians. Niazi had penned a polemical booklet critical of the Christian faith.

Bhutto, too, realized his betrayal of religious minorities. Hence, in 1973, a ‘Minority Conference’ was held with some pomp and show. Bhutto from the platform of this conference promised equal rights to the minorities. However, in 1974, the constitution was amended to excommunicate the Ahmedis.

Peter Jacob, therefore, concludes, “Nationalisation of Church-run schools, apart from its existential fears linked to identity, economy and social vibrancy, damaged the potential of political integration and enrichment.”

This situation translated into a near-total erosion of Bhutto’s support, in the Punjab, among Christians. Post-Bhutto era, a process of denationalization was initiated. However, of the 118 nationalised institutions, only 58 have been returned to the church. The battle for the rest is on. As an aside, the report points out that the legislation to facilitate the return of nationalized schools to the former owners has not benefitted the Ahmedis. The Ahmedia community continues to struggle for the schools they lost to nationalization.

Half a century after the nationalization of schools with unfortunate consequences for the Christian community, another populist and opportunist is at the helm. His SNC is likely to further isolate the non-Muslim students. Hence, Peter Jacob’s and Dr Kamran’s contribution to an overall debate on the education sphere is indeed timely.

Despite many merits, one cannot help note an unsympathetic treatment of Bhutto’s overall policy of nationalizing educational institutions. While there are convincing arguments substantiated by considerable empirical evidence to prove the flawed nationalization of missionary schools, a generalized dismissal of overall nationalization policy is not indeed nuanced. Declaring Bhutto’s educational nationalization as political sounds ideological rather than argumentative. Zia’s denationalization was equally political. Also, what is it that can be discounted as apolitical? Secondly, blaming nationalization for declining standards only describes the fact. Explanations lie elsewhere. For instance, Ziafication damaged the education more than nationalization. Or what about shoe-string budgets to run the education ministries. Nationalisation at least brings state into education and undermines the cruelty of neoliberal order that has commodified the education and reduced the school-workers to the conditions of slaves.

As both authors of the report are known for their pro-people views, one hopes their criticism of nationalization will trigger a more nuanced debate. One may argue over the merits and demerits of Bhutto’s nationalization, one conclusion meantime can be easily drawn from this brilliantly researched report: any educational policy in Pakistan should take into account the vulnerable situation of religious minorities. Not merely their grievances should be addressed (one immediate measure would be to return the remaining schools to the Church), extra resources should be invested to end economic, cultural, social and educational marginalization of Pakistan’s religious minorities. Most importantly: minoritization on the confessional basis should stop.

The writer is an assistant professor at Beaconhouse National University

With an incisive preface by Dr Yaqoob Bangash, the report consists of two chapters: Peter Jacob’s chapter analyses the impacts of nationalization on the lives of Christian community while Dr Tahir Kamran foregrounds the consequences of nationalization on the quality of education.

Under Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto’s leadership, 3,334 institutions were nationalized on March 15, 1972. Nationalized institutions included 1,826 schools, 346 madrassas, 155 colleges and five technical institutes. 118 of them were church-run institutions.

Though missionary schools/colleges constituted a small portion of the overall drive yet they had terrible consequences for Christians.

Let us begin with the economic fallout for the Christians in the country. These schools offered job opportunities to a community otherwise marginalized in the job market. Likewise, it proved to be a big blow to literacy rates among the Christians.

By 2019, the share of Christian teachers in the former missionary schools had dropped to 9 percent while the Christian students constituted only 16 percent in these schools. Likewise, the loss of these schools also meant a loss of income for the church, let alone their formidable soft power.

Secondly, an important avenue to forge inter-religious harmony was lost since many middle-class families would send their children to missionary schools since these quality-education schools were not as expensive as the privately-run schools. Simultaneously, discriminations faced by the Christian students at public schools, especially on the countryside, furthered Christians’ ghettoization.

Thirdly, as Dr Kamran points out, the state-takeover of the missionary schools was against the spirit of nationalization. Since nationalization was aimed at providing access to quality education, to all and sundry, by ending a system of for-profit schools. The schools run by the church were neither commercial nor elite.

Lastly, such is the logic of the Islamified schooling system (and the society in general) that the Christian students have to opt for Islamiat instead of Ethics. The following figures suggest the cruel exclusion of Christian students: In 2018, 0.07 percent of the Christian students studied Ethics at Grade 5 level, 0.06 percent at the Grade 8 level. Likewise, 80 percent (out of 15,917 students) opted for Islamiat in the matriculation years. At Intermediate level (out of 7,405), 1.7 percent studied Ethics, 8.8 percent Civics while 90 percent ‘opted’ Islamiat.

“While attacking the self-respect and identity of religious community might not have been the primary aim of the 1972 nationalisation…this action did severely undermine Christian’s confidence in Pakistan,” Dr Bangash observes.

The Christian community understood the colossal loss Bhutto was inflicting on the community. Hence, they started agitating. The agitation took a tragic turn when a 2,000-strong peaceful demo in Rawalpindi, on 30 August 1972, was brutalized by the police. Three demonstrators: R. M. James, Nawaz Massih and an unidentified person, were shot dead while another 25 were injured. Over a dozen were also arrested.

Ironically, Bhutto was elected from a Lahore constituency with over 70,000 Christian residents. Without Christian votes, he would not have won in Lahore. He vacated the seat because he wanted to retain his Larkana seat. In his place, Mehmood Qasori was elected as the PPP candidate in the by-election. Hence, Christians were double betrayed because Bhutto had also presented himself as a champion of the subaltern.

The entire report justifiably is an indictment of Bhutto’s opportunistic politics. For instance, while 118 Urdu-medium Christian schools were nationalized, the elite schools meant for the gentry were exempted. Bhutto also inducted Kausar Niazi, a maverick mullah, in his cabinet which further alienated the Christians. Niazi had penned a polemical booklet critical of the Christian faith.

Bhutto, too, realized his betrayal of religious minorities. Hence, in 1973, a ‘Minority Conference’ was held with some pomp and show. Bhutto from the platform of this conference promised equal rights to the minorities. However, in 1974, the constitution was amended to excommunicate the Ahmedis.

Peter Jacob, therefore, concludes, “Nationalisation of Church-run schools, apart from its existential fears linked to identity, economy and social vibrancy, damaged the potential of political integration and enrichment.”

This situation translated into a near-total erosion of Bhutto’s support, in the Punjab, among Christians. Post-Bhutto era, a process of denationalization was initiated. However, of the 118 nationalised institutions, only 58 have been returned to the church. The battle for the rest is on. As an aside, the report points out that the legislation to facilitate the return of nationalized schools to the former owners has not benefitted the Ahmedis. The Ahmedia community continues to struggle for the schools they lost to nationalization.

Half a century after the nationalization of schools with unfortunate consequences for the Christian community, another populist and opportunist is at the helm. His SNC is likely to further isolate the non-Muslim students. Hence, Peter Jacob’s and Dr Kamran’s contribution to an overall debate on the education sphere is indeed timely.

Despite many merits, one cannot help note an unsympathetic treatment of Bhutto’s overall policy of nationalizing educational institutions. While there are convincing arguments substantiated by considerable empirical evidence to prove the flawed nationalization of missionary schools, a generalized dismissal of overall nationalization policy is not indeed nuanced. Declaring Bhutto’s educational nationalization as political sounds ideological rather than argumentative. Zia’s denationalization was equally political. Also, what is it that can be discounted as apolitical? Secondly, blaming nationalization for declining standards only describes the fact. Explanations lie elsewhere. For instance, Ziafication damaged the education more than nationalization. Or what about shoe-string budgets to run the education ministries. Nationalisation at least brings state into education and undermines the cruelty of neoliberal order that has commodified the education and reduced the school-workers to the conditions of slaves.

As both authors of the report are known for their pro-people views, one hopes their criticism of nationalization will trigger a more nuanced debate. One may argue over the merits and demerits of Bhutto’s nationalization, one conclusion meantime can be easily drawn from this brilliantly researched report: any educational policy in Pakistan should take into account the vulnerable situation of religious minorities. Not merely their grievances should be addressed (one immediate measure would be to return the remaining schools to the Church), extra resources should be invested to end economic, cultural, social and educational marginalization of Pakistan’s religious minorities. Most importantly: minoritization on the confessional basis should stop.

The writer is an assistant professor at Beaconhouse National University