In the vast, arid expanse of the desert, where the scorching sun casts its relentless gaze upon the shifting dunes, a remarkable figure emerges – Poonam Paschal, a desert-based linguist and development practitioner. Equipped with insatiable curiosity and an unwavering passion for unraveling the mysteries of language, this intrepid scholar embarks on a unique and captivating journey, navigating the linguistic landscapes of the world's most unforgiving terrains. He delves into the languages spoken by desert-dwelling Parkari communities, unearthing the unique phonetic nuances and syntactic structures that have evolved over centuries in isolation.

Poonam Paschal is the founder of the Parkari Community Development Programme (PCDP), a non-profit community-based organisation. Its aim is to empower the Parkari minority living in Sindh, Pakistan, and promote a mother-tongue-based multilingual education program for children and adults. Recently, I interviewed him. Here is excerpt focusing primarily on his Parkari Language Development Approach.

Zaffar Junejo (ZJ): Your story is already a part of the Parkari book, perhaps its Parkari title is Gareb Sokro (a Poor Boy). Could you elaborate on it for our readers?

Poonam Paschal (PP): You are absolutely correct. The story or lesson was tailored to suit young readers, with carefully chosen words and constructed sentences suitable for their age group. However, if you allow me to narrate my story, I would like to start from the year 1962. This year is etched in my memory, as it was when I travelled for 5-6 days’ journey on foot with my family from Nagarparkar to Matli. My father was going to meet his brother, who had already embraced Christianity. Matli was an entirely new experience for me - everything seemed new, from regular meals and paved roads to a clean environment, bearable sunlight and an ornate church building. I was captivated and mesmerised, and I momentarily forgot about the harsh and simple life of Nagarparkar in the Thar Desert. Later, my father passed away, but I can't recall whether I was informed of his death or if I simply forgot.

ZJ: How did you continue your education?

PP: I was enrolled in a missionary school, a Church School, where a Dutch priest took responsibility for my education. Later, I was moved to Nawabshah, now known as Benazirabad, where I attended a church-managed school and lived in a hostel. I completed my 8th Standard there, and my education continued to be supported by the same Dutch priest.

ZJ: It seems like your education took place in various towns and cities?

PP: Yes, I had the opportunity to study in Matli, Nawabshah, Sanghar and Hyderabad. These towns and cities provided me with both formal and informal learning opportunities. I must also mention the churches and dioceses of these places, which welcomed me with motherly love. I consider myself fortunate that kind-hearted priests helped shape and refine my personality during those formative years. I am deeply grateful to them.

ZJ: You did a variety of odd jobs just to get by each day?

PP: Indeed, my early life was a constant struggle. I took on a wide range of jobs that came my way, including working as a daily labourer, a watchman, a cleaner and even a woodcutter. I vividly remember these experiences because I worked in these roles for extended periods.

ZJ: Were you also a photographer?

PP: When I look back on those days, I consider them an adventure. I used to travel to remote villages and hamlets with cameras, rolls of film and photo frames. It was a tiring, risky, and challenging job. Sometimes, I would travel over ten kilometres to reach a village, only to have the villagers initially refuse to be photographed. They would ask me to wait until they finished their work in the fields, then take baths, change their clothes, and only then allow me to take their photos. I pursued this work for a considerable time before eventually moving on to other jobs. In 1970, I relocated to Hyderabad and found employment at St Elizabeth's Hospital, where I worked in a low-paying, non-technical position. This job opened up new opportunities for me, and it was there that I met my future wife.

ZJ: Given your background, how did you get involved in charity and welfare work?

PP: During my time at St Elizabeth's Hospital, I realised that I owed my current position in life to the care and goodwill of some individuals—priests, fathers, and friends. I felt a strong urge to give back and serve the Parkari community of the Nagarparkar area, to whom I belonged. I recognised that doing good work didn't necessarily require abundant resources or wealth. It was more about one's mindset and humility. Subsequently, my wife and I started serving our Parkari community.

ZJ: What were the challenges of community work in those days?

PP: There were numerous challenges, including long distances, difficult terrain, frequent migrations, and issues related to education and women's health. However, one major challenge that we encountered was the issue of the Parkari language. It was the only means of communication with women, children, and the elderly in our community. Therefore, we made Parkari language the central focus of our initiatives, building other support mechanisms around it.

ZJ: Could you tell us more about your Parkari language initiative?

PP: Before addressing that question, it's essential to shed light on the Parkari community. It's estimated that there are approximately 1.5 million Parkari speakers, all of whom are scattered across lower Sindh. Unfortunately, they occupy a lower social status within the caste system and work as farm laborers. Now, to address your question, the development of Parkari as a written language with a standardised orthography began in 1983.

ZJ: What were the challenges involved in this initiative?

PP: Initially, we faced two fundamental challenges: developing a standardised Parkari alphabet and deciding on a method for representing the sounds of the language with written symbols. After extensive debate and consultations with linguists, we decided that the writing system of the Sindhi language would be suitable for developing the Parkari language. Several factors influenced this decision, including the presence of many Sindhi words in the Parkari language (though pronounced differently) and the immediate linguistic environment being predominantly Sindhi rather than Urdu or English. Therefore, we adopted the Sindhi script for writing the Parkari language. We observed that Parkari boys and girls in primary schools were already reading Sindhi books, so using the Sindhi script for Parkari made sense and proved to be a wise decision.

ZJ: What were the next steps in this endeavour?

PP: In 1984, Mr Richard Hoyle (a British national) and I initiated the Parkari Language Project with the aim of developing Parkari as a written language with a standard orthography. Soon after, we formed the Parkari Language Committee to decide how Parkari should be written and what kinds of literature should be produced. Mr. Sajjan Parmar became the chairman of this committee, and he even issued a handwritten magazine in Parkari called Prem Parchar (Propagation of Love). In 1985, Richard and I produced the first Parkari books. We continued our efforts and successfully created a substantial amount of reading material, including books on health, education, and religious topics.

ZJ: Can you please share with us the key publications that have contributed to the development of the Parkari language?

PP: Certainly. As most linguists and language experts agree, preserving folk literature and developing thesauruses and dictionaries are essential for language development. Recognizing the importance of this, I took the initiative to gather and compile Parkari proverbs and riddles. In 1991, we published a book titled Geon Ro Guppat Dhan (The Hidden Treasure of Wisdom). This book contained a collection of 500 proverbs and 250 riddles in Parkari. In line with our vision, another book focusing on the history of Parkari culture, titled Lok Sagar Ja Moti (Pearl of the Ocean), was authored by Mr. Paru Mall and published in 2000. Furthermore, a book titled Haas Rai Got (In Search of Truth), authored by me, was published in 2018. This book presents inspiring stories aimed at establishing standards and values in society.

In 2002, we published the first edition of the Parkari to Parkari and Urdu and English Dictionary, with Mr. Richard Hoyle and me as editors. In 2022, with the assistance of Mr. Bhooro Lal from Nagar Parkar, we prepared and released an expanded version of the Parkari to Parkari Dictionary. Since 2005, our organisation has been publishing the Quarterly Parbhat (Dawn) Magazine in Parkari, with the purpose of promoting Parkari as the mother tongue of the Parkari community.

ZJ: Can you describe how you transitioned into the Mother Tongue-Based Multilingual Education Initiative?

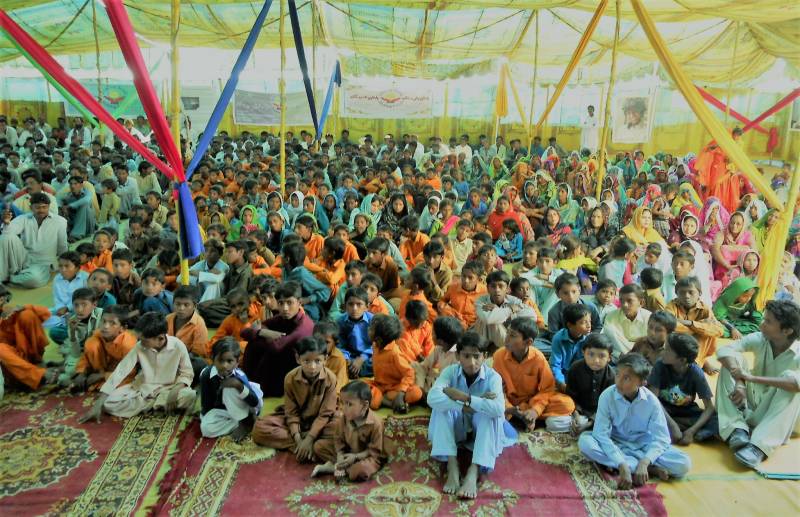

PP: Certainly. The Mother Tongue-Based Multilingual Education (MTB-MLE) program has its roots in our Parkari Language Development Initiative. This educational approach emphasises using a child's mother tongue as the medium of instruction during the early years of schooling. The pilot project for MTB-MLE was initiated in 2000 with the help of Canadian couple Mr. & Mrs. Steve and Vicky Simpson. It was structured as a two-year pre-primary education program, with Parkari serving as the language of instruction. The primary focus was on helping students acquire literacy skills, starting with their mother tongue and subsequently transitioning to Sindhi. In the latter half of the second year, teachers introduced oral Sindhi, guiding the children in transferring their acquired literacy skills from Parkari to Sindhi. At the end of Year 2 (equivalent to Grade 1 in government schools), Parkari children took the government Grade 1 Sindhi language examination). The herculean task was to develop teaching materials and train teachers for this approach.

ZJ: How do you assess the success of the MTB-MLE program?

PP: I believe that our Mother Tongue-Based Multilingual Education (MTB-MLE) program has demonstrated significant positive impacts on students' learning outcomes. It has influenced the education of minority children by ensuring inclusivity, respecting cultural diversity, and enhancing the overall quality of learning for students from various linguistic backgrounds.

ZJ: Are there other mother tongues spoken in the Thar region, and are they adopting a similar approach to MTB-MLE?

PP: There may be many other mother tongues spoken in the Thar region, although a fresh linguistic survey hasn't been conducted to confirm this. However, I have come across several languages, including Kachhi Gujarati, Dhatki, Thardhari, Oddki and Marwari. Encouragingly, it appears that all of them are adopting a similar Mother Tongue-Based Multilingual Education (MTB-MLE) approach, following our lead.

ZJ: What are your future plans for your initiatives?

PP: My vision is to establish a community-based sustainability model on the basis of Parkari Community Development Network we established. It includes two key elements; the ‘Peoples' Ashram.’ characterised by a spirit of giving and would be grounded in traditional and religious values. And another key feature would be fostering unity and a sense of Pariwar (family) among its members, nurturing a sense of responsibility and social cohesion. Members would have access to collective resources and this sustainability model would be led by setting examples of virtue and purity.