‘Yes, men were delighted that they were led again as a herd and that there had been lifted from them at last so terrible a gift, the gift of freedom.”

– From the novel The Brothers Karamazov by Theodore Dostoevsky

There must still be a number of people who, like this commentator, remember Lt General Mohammad Azam Khan, a Pashtun who was a career military professional and, moreover, the exemplar of outstanding executive ability. Outside the military, he first came to the notice of the general public in 1950, when he very ably directed operations during the catastrophic Punjab floods of that year.

In 1953, the city of Lahore erupted in riots, triggered by the anti-Ahmaddiya agitation of the religious parties. While much has been written about the Munir Commission’s well-known findings on that issue, it is also worth commenting on the relentless but even-handed manner in which Azam Khan and his troops quickly restored order to the city.

In October 1958, Azam was appointed as the senior-most Minister in Ayub Khan’s Cabinet, wherein he held various portfolios. Not only was this Cabinet as a whole famed for giving shape to Ayub’s reputed ‘Golden Page’ in Pakistan’s history, but Azam is especially remembered for his contributions, including his outstanding work in rapidly resolving long standing problems of the Mohajirs at that time, and for the rehabilitation of refugees at Korangi Colony.

Azam Khan became Governor of then East Pakistan in 1960, where he rendered exceptional service during the two great tidal bores and cyclones of 1960 that devastated the coastal districts. He worked day and night for over one and a half months, and personally supervised the distribution of relief and the reconstruction work. Over the next two years, his great energy and drive made him so popular that he came to be popularly called ‘Azam Chacha’. He fell out with Ayub over the farcical Basic Democracies programme and tendered his resignation in 1962. A mammoth public gathering of people turned up at a civic farewell at the Dhaka Stadium. Braving a burning sun and threats of rain, they are said to have rent the sky with full-throated shouts of “Azam Khan Zindabad”.

Nature and politics abhor vacuums

Clearly, it is possible to achieve enthusiastic popular acclaim on the basis of sheer performance without resorting to false histrionics and harangues. In fact, it is hard to recall any other figure in our nation’s sad history to have received the kind of adulation Azam Khan did in the former East Pakistan... on the basis, not of promises made, but of performance delivered.

Now, my reader may well be wondering at this reminiscence over a figure from the yesteryears. The point is that it is precisely Azam Khan’s kind of vigorous, even-handed delivery of positive results that is the strongest feature of the way in which our armed forces are believed to act. And it is this kind of perceived ability that led so many members of our educated upper and upper-middle classes to applaud the periodic military take-overs which in fact blighted our history and stunted our political development.

Consider. The colonial era legacy of Pakistan left us with two distinct structures of power, built around different sets of elite groups. One was a ‘political’ or elected structure (president, prime minister, parliament, political parties, etc). The other was an ‘administrative’ or unelected structure (military, bureaucracy, judiciary, the professions, etc), which is in the habit of exercising real power because it is they who actually pull the levers and, from time to time, seized power. This dichotomy was earlier identified by Professor Hamza Alavi. Because of its command over firepower, the military is the dominant partner in this ‘administrative’ structure.

Now, the military mind’s preoccupation with clear objectives and effective action is exceedingly attractive. But the downside of the military’s way of doing things could be clearly discerned in Azam Khan’s boss, the late Field Marshall. Ayub’s regime was notable for being able, efficient and highly effective, for having written what many have referred to as a Golden Page in Pakistan’s history. The problem was that the mind of our good Field Marshall, was not attuned to the complexities of competing political ideals and the many grey areas in society.

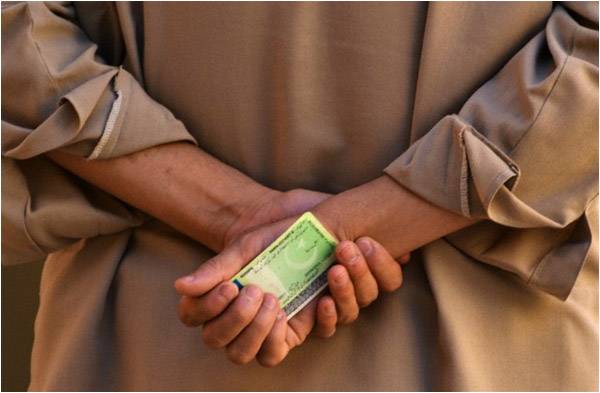

In defiance of already firmly established preferences for the parliamentary system, Ayub’s 1962 Constitution created an all powerful executive President... and one unfettered by such ‘alien’ concepts as Separation of Powers. Instead of a popularly elected Legislature, an electoral college of 80,000 easily purchasable Basic Democrats was created, to vote for the parliamentarians and for the President. Where the ethnic diversity and divided geography of the country all too obviously called for federal arrangements, the 1962 Basic Law was unitary in structure, with centrally nominated unelected Governors running the two wings of the country and all the various ethnic regions of the Western Wing combined into a single ‘One Unit’. As any first-year student of politics could have foretold, the 1962 document was unworkable. It disintegrated in the massive uprisings of 1968-69, by most segments of society. And this was only a precursor to the cataclysm of 1971, presided over by Ayub’s military successor.

Military men are human. And, not only can humans err, they can also commit unspeakable, long-term evil. Need we remind ourselves of General Zia? They can also be foolishly arrogant, deluded into blindness by their own egos, as Pervez Musharraf was.

However, today, there is a consensus favouring the continuity of constitutional democracy. I believe that the voter turnout in the last elections, in defiance of Taliban threats, was a positive sign, principally because this turnout meant that those groups and classes who had not previously been accustomed to voting, who believed in governmental effectiveness rather than what Bhutto called “the noise and chaos of democracy”, and who had in fact formed the bedrock of support for every military takeover, had now put their faith in the ballot box.

This was an important development, which augured well for the nation. Unfortunately, the political personage who had most attracted these new voters to stream towards the polling booths, chose to launch a protracted series of senseless Dharnas and agitations against the basic institutions of constitutional democracy. Other seriously worrying institutional factors include, first, the weakness and perceived poor performance of the PML-N government; second, the gathering total eclipse of Pakistan’s oldest and once largest political party, the PPP; and, third, the intellectual mediocrity (with few exceptions) of the present set of cabinet members and parliamentarians and their concomitant failure to deliver on their responsibilities.

Nature and politics both abhor vacuums. Other entities and institutions take control of that which the elected political structure fails to manage effectively. Now, I am not suggesting that the boots of Brigade 101 will any time soon be heard marching up Constitution Avenue in anything other than a parade formation. Nor is someone in Rawalpindi composing his “My Dear Countrymen” speech. But clearly the outlook for our ineffective political democrats is not at the moment bright and the word ‘politician’ is rapidly becoming a term of ridicule and disgust.