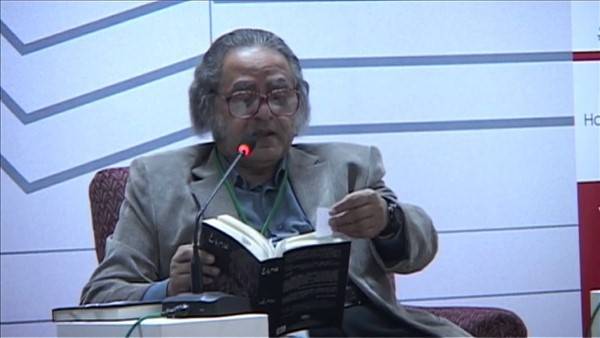

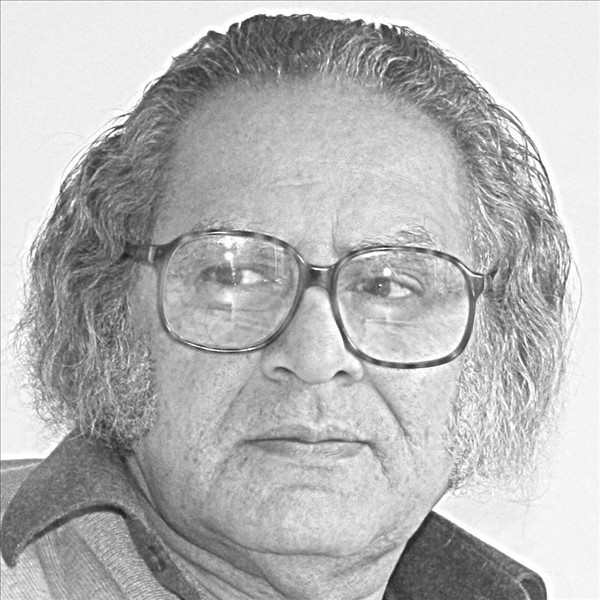

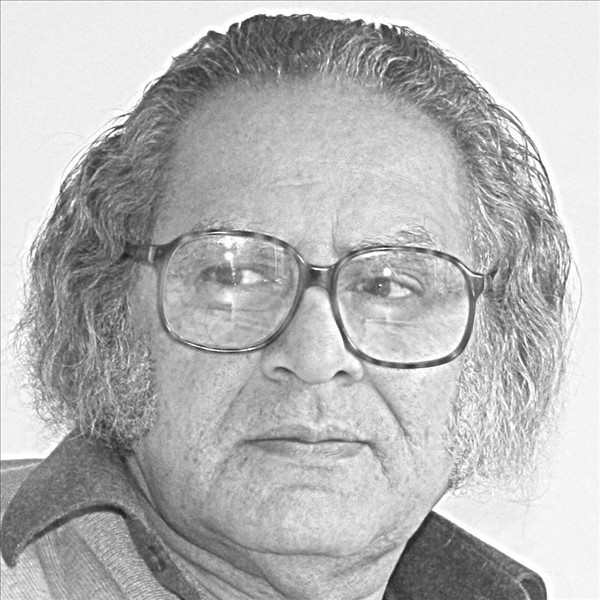

While his unique and experimental novels appeal to the young, resulting in the “Ghulam Bagh group” based on the title of one of his novels, older Pakistanis remember Mirza Athar Baig owing to his classical drama serial, Doosra Asmaan which went on air on Pakistan Television. I could never figure out why he quitted writing for television.

However, I did notice his lamentation at the neglect of his scripts while attending a seminar on script-writing at my university. A few days after that, I was asked by the chief editor of The Ravi 2016, Hafsah Sohail Rathore, to write an article on Mirza Athar Baig. I planned to go through all the genres he has worked in, as a result of which I first of all searched for his drama serials on Youtube. All this was possible due to my immense interest in classical Pakistani drama. I came across Hissaar written by him and directed by Ayub Khawar, one of the finest Pakistani directors. The characters of Hissaar would often talk about literary figures, paperback editions of books and other such topics – discourses on which are scarcely found in modern drama serials. One of the characters performed by Samina Peerzada would shock the viewers now and then by enacting too brave a woman for our society.

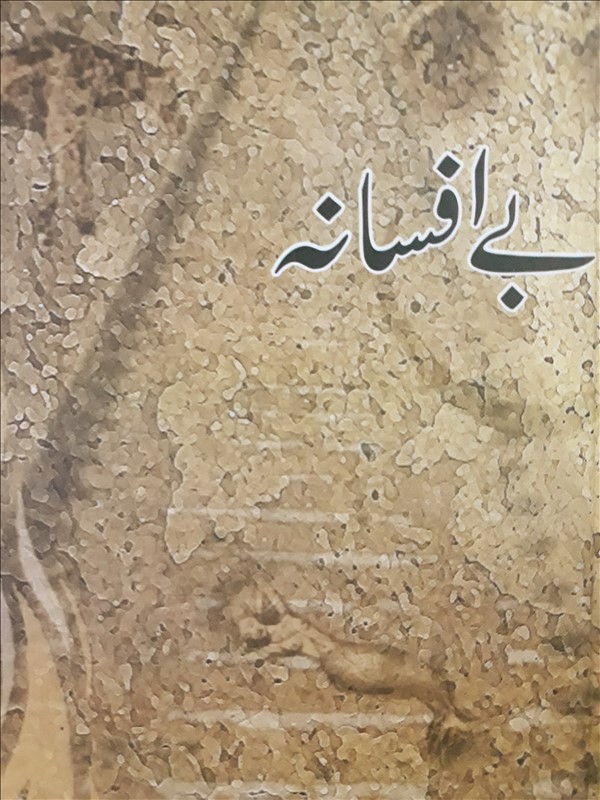

After having watched a few episodes of it, I ordered Mirza Athar Baig’s collection of short stories, Be-Afsaana. One of the stories from the collection was titled Na-Mukammal (Putla) Kahani, translated by Aqsa Ijaz as An Unfinished (Effigy) Story for The Ravi 2015. It was when I read this story that clips from Hissaar, Mirza Sahib’s disappointment at his scripts and his abandonment of drama-writing simultaneously hit my mind – and it all snowballed into what I believe to be a probable stimulus for the creation of An Unfinished (Effigy) Story.

This story is divided into two sections, each making use of a different narrative technique. The first part, making use of omniscient narrative, is apparently the story of a gate-keeper named Sirajdin who has been asked by two political leaders to prepare an effigy of a political opponent which has to be burned in a protest. This one-liner itself has three ideas hidden in it. If taken as an allegory, the gate-keeper is what the writers were reduced to after the privatisation of Pakistani TV channels – subordinates asked to write on topics demanded by other people by snubbing their own imagination. The fact that the gate-keeper is given only one night to prepare the effigy subtly refers towards the time constraints in which the writers would be asked to conclude a certain piece of writing, thus not getting time to reflect properly and resulting in figures that are not really characters but mere puppets – lifeless, forced and developed in alacrity. Hence, Sirajdin, the gatekeeper becomes a writer stranded in an era of commercialism, Hashim Sahib and Rehman Sahib become dominant producers and the effigy assumes the shape of a story’s character.

In the next section of the story, which is written in the form of a letter, the speaker narrates the rest of the story to the recipient in indirect speech, telling them that the effigy is now somehow prepared and is made to burn as per the plan of the political party. But along with it, another figure also seems to burn, probably the gate-keeper’s own, for it “cries out” in front of people. It suggests that the gate-keeper, or the writer as we are reading him, when he burns himself, frees himself of all such duties and does not continue to live as a creator or a writer. On a deeper level, the action points at the death of a creative writer along with his or her forcefully written stories due to the commercialism of Pakistani television. Commercialism and forced writings are also hinted at when the author writes:

“You know how I hate political stories, and yet more and more stories that try to mirror the issues of today.”

While to the reader, it is a note by the story’s speaker telling how or she, as a creative writer, cannot always snub their imagination and remain ‘realistic’ all the time, but it also seems to be an endnote written by Mirza Athar Baig for the producers before completely abandoning drama-writing.

Watching Mirza Sahib’s drama serials and reading this story by him afterwards makes one realise why with the privatisation of Pakistani television and the entrance of a large number of producers meaning business and not creativity, many creative writers like Mirza Athar Baig, Asghar Nadeem Syed, Haseena Moin, Bano Qudsia, Amjad Islam Amjad, Anwar Maqsood and Ashfaq Ahmad either stopped writing or became writers who would pen down stories only if someone insisted a lot.

Mirza Athar Baig, though he left writing in this genre which grew too commercial for his taste, continued to exhibit his creative skills in other genres of literature such as the novel and the short story. Every work of his has been an experimentation at narrative techniques and at ideas and plots. This rendered one of his novels Ghulam Bagh the third biggest novel in Urdu literature after Aag Ka Dariya and Udaas Naslein. Proof of his off-beat activities has also been presented through the fact that as the supervisor of the Dramatics Club of GCU, he has broken the eight-year-long chain of presenting only Urdu dramas, and since the 2017, has started to adapt English plays. He has been bearing criticism on bringing about a sudden change, but is showing perseverance and trying to convince the viewers to start digesting something different from what they have already been experiencing for almost a decade.

The writer is a student of English Language and Literature at GCU, Lahore and can be reached at m.ali_aquarius85@yahoo.com

However, I did notice his lamentation at the neglect of his scripts while attending a seminar on script-writing at my university. A few days after that, I was asked by the chief editor of The Ravi 2016, Hafsah Sohail Rathore, to write an article on Mirza Athar Baig. I planned to go through all the genres he has worked in, as a result of which I first of all searched for his drama serials on Youtube. All this was possible due to my immense interest in classical Pakistani drama. I came across Hissaar written by him and directed by Ayub Khawar, one of the finest Pakistani directors. The characters of Hissaar would often talk about literary figures, paperback editions of books and other such topics – discourses on which are scarcely found in modern drama serials. One of the characters performed by Samina Peerzada would shock the viewers now and then by enacting too brave a woman for our society.

It was when I read this story that clips from Hissaar, Mirza Sahib's disappointment at his scripts and his abandonment of drama-writing simultaneously hit my mindmind

After having watched a few episodes of it, I ordered Mirza Athar Baig’s collection of short stories, Be-Afsaana. One of the stories from the collection was titled Na-Mukammal (Putla) Kahani, translated by Aqsa Ijaz as An Unfinished (Effigy) Story for The Ravi 2015. It was when I read this story that clips from Hissaar, Mirza Sahib’s disappointment at his scripts and his abandonment of drama-writing simultaneously hit my mind – and it all snowballed into what I believe to be a probable stimulus for the creation of An Unfinished (Effigy) Story.

This story is divided into two sections, each making use of a different narrative technique. The first part, making use of omniscient narrative, is apparently the story of a gate-keeper named Sirajdin who has been asked by two political leaders to prepare an effigy of a political opponent which has to be burned in a protest. This one-liner itself has three ideas hidden in it. If taken as an allegory, the gate-keeper is what the writers were reduced to after the privatisation of Pakistani TV channels – subordinates asked to write on topics demanded by other people by snubbing their own imagination. The fact that the gate-keeper is given only one night to prepare the effigy subtly refers towards the time constraints in which the writers would be asked to conclude a certain piece of writing, thus not getting time to reflect properly and resulting in figures that are not really characters but mere puppets – lifeless, forced and developed in alacrity. Hence, Sirajdin, the gatekeeper becomes a writer stranded in an era of commercialism, Hashim Sahib and Rehman Sahib become dominant producers and the effigy assumes the shape of a story’s character.

In the next section of the story, which is written in the form of a letter, the speaker narrates the rest of the story to the recipient in indirect speech, telling them that the effigy is now somehow prepared and is made to burn as per the plan of the political party. But along with it, another figure also seems to burn, probably the gate-keeper’s own, for it “cries out” in front of people. It suggests that the gate-keeper, or the writer as we are reading him, when he burns himself, frees himself of all such duties and does not continue to live as a creator or a writer. On a deeper level, the action points at the death of a creative writer along with his or her forcefully written stories due to the commercialism of Pakistani television. Commercialism and forced writings are also hinted at when the author writes:

“You know how I hate political stories, and yet more and more stories that try to mirror the issues of today.”

While to the reader, it is a note by the story’s speaker telling how or she, as a creative writer, cannot always snub their imagination and remain ‘realistic’ all the time, but it also seems to be an endnote written by Mirza Athar Baig for the producers before completely abandoning drama-writing.

Watching Mirza Sahib’s drama serials and reading this story by him afterwards makes one realise why with the privatisation of Pakistani television and the entrance of a large number of producers meaning business and not creativity, many creative writers like Mirza Athar Baig, Asghar Nadeem Syed, Haseena Moin, Bano Qudsia, Amjad Islam Amjad, Anwar Maqsood and Ashfaq Ahmad either stopped writing or became writers who would pen down stories only if someone insisted a lot.

Mirza Athar Baig, though he left writing in this genre which grew too commercial for his taste, continued to exhibit his creative skills in other genres of literature such as the novel and the short story. Every work of his has been an experimentation at narrative techniques and at ideas and plots. This rendered one of his novels Ghulam Bagh the third biggest novel in Urdu literature after Aag Ka Dariya and Udaas Naslein. Proof of his off-beat activities has also been presented through the fact that as the supervisor of the Dramatics Club of GCU, he has broken the eight-year-long chain of presenting only Urdu dramas, and since the 2017, has started to adapt English plays. He has been bearing criticism on bringing about a sudden change, but is showing perseverance and trying to convince the viewers to start digesting something different from what they have already been experiencing for almost a decade.

The writer is a student of English Language and Literature at GCU, Lahore and can be reached at m.ali_aquarius85@yahoo.com