There are two compelling but contradictory principles that make reporting on gender violence awkward and extremely difficult. The first is the bedrock of any justice system: a person is innocent until proven guilty. The legal norm necessitates us in the media to generally take a similar approach against people or groups suspected of criminal activity—this is why a person is charged with murder rather than called a murderer. You are called a suspect while in custody, not a criminal or convict.

The second principle, whose application has been made de rigueur thanks to the work done by activists everywhere, is to believe the victims of gender violence as a point of departure. The underlying acknowledgement is that a system (especially in Pakistan) designed to benefit men at women’s expense makes it difficult at every step for a woman to seek justice against her attacker. The first hurdle in her way is our attitude (You were asking for it. You should take it as a compliment), then there are the laws (Pakistan’s notorious Hudood Ordinance, to name one), the sluggish and costly process by which guilt or innocence is determined, and finally even if a woman wins a conviction against her attacker, a shame-based society such as ours would still punish the woman for being so brazen as to be vocal about her experience. Indeed, at this stage we often find women raking the victim over the coals for speaking out.

Outside Pakistan though, societies are incrementally moving towards taking accusations of sexual harassment seriously, as a slew of famous personalities such as Bill Cosby, Woody Allen, Roger Ailes, and American president Donald Trump have seen when they came under intense media scrutiny or faced legal proceedings and punishment.

Cases of sexual harassment throw up a peculiar incongruity. How can the media assume the innocence of the accused while believing the victim simultaneously? As humans, we generally like to order our lives in morally unambiguous terms, inhabit a world with good guys and bad guys, and rarely anything in between. And thus, when someone accuses someone else of sexual harassment, most of us want to believe the victim as innocent, and demonize the perpetrator. The problem is, neither course of action may actually be based on the truth, and even if it is, we cannot know for sure.

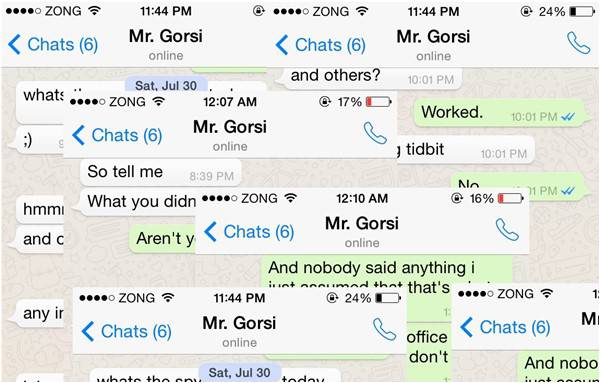

Take the recent case of journalist Zubaria Jan accusing her former boss Salman Masood of sexual harassment in a blog post. (She also accused him of being behind the Twitter account @Saroor Ijaz, but the validity of that accusation is not the subject of this article.) The screenshots that Zubaria Jan takes of her Whatsapp and Twitter conversations with the person who she alleges is Salman Masood do not incriminate Masood, but they do not excuse him either. Masood denied the accusations on Twitter, calling them “frivolous” and “malicious”.

Without witnesses or evidence, it is impossible to know with certainty what actually took place, but in their absence, there are still some decisions to make after someone chooses to go public with the matter. The first decision perhaps lay with Zubaria Jan on how to deal with the complaint(s) she had. Ideally organisations should have in-house confidential sexual harassment committees that tackle cases such as hers. Another way of handling them is for the aggrieved party to write to the editor.

But for now, and given what little we know, one question to ask is whether journalists should reserve judgement until more facts are revealed in such circumstances. How seriously ought the media take Zubaria Jan’s claims without an investigation or independent collection of evidence? Should the media be spurred by a blog post take it upon itself to determine the answers of a sexual harassment case given the absence of formal corporate and/or judicial procedures to address such accusations?

First, it must be acknowledged that while the media has an important role in investigating, analysing and researching information that is sometimes essential to criminal or civil cases, that role is limited. The court of public opinion is different from state courts which is why it would be disingenuous and even harmful to determine guilt or innocence in the media without being able to present all the evidence. The presumption of guilt for someone a court has determined to be innocent is tantamount to defamation, if not necessarily in the legal definition of the word.

When there is no evidence, the media’s judgment on a particular case or individual will always be limited. In Bill O’Reilly’s recent case, it emerged that he settled out of court with his accuser. The settlement is not indicative of O’Reilly’s guilt or innocence. (O’Reilly’s lawyer said, “There is absolutely no basis for any claim of sexual harassment.”) He might have been innocent but perhaps wished not to have his name dragged through the mud. Or he may have been guilty and thought it best to settle discreetly. Either way, the available facts are not enough to determine guilt. That said, determining the guilty party can only be the end result of good journalistic work, and that starts with taking the accuser’s allegations seriously and investigating. Just as one follows up on any tip from a source, a journalist’s job is to dig further, to ask questions of many to people, to find evidence—documents, recordings, photographs—that can help determine what really happened.

Whatever the journal or the journalist’s political leanings and biases, we are all required to verify and cross-check what we’ve been told, and at the same time maintain the trust of our sources. It’s a difficult position to maintain, as the catastrophe that was the Rolling Stone’s story about rape on university campuses demonstrated. In their case, solely believing the victim ‘Jackie’ as she was called, and not others, meant that in the end the story was shredded when put under actual scrutiny by a Columbia School of Journalism investigation. The writer meant to be supportive and ethical in her support for the victim, but it was bad journalism, and may have caused more damage to rape culture on college campuses than champion their cause.

‘Trust, but verify’ might be an adage as useful to journalists as it was to the Cold War. It is fundamental not to dismiss any accusations of sexual violence offhand, and as with all other stories, journalists ought to investigate those accusations to reach as close to the truth as they can. Although it is entirely understandable when journalists fail to do so, I’d much rather it be because of an absence of evidence than structural sexism.

In Pakistan, the terrain is even more difficult. In the absence of a robust legal system or in-house structures to deal with harassment in office settings (especially when it comes to freelance professionals), there is little faith that victims of gender violence will get the justice they seek. In such cases journalists can assist the accused in producing the evidence they need, and give a voice to the injustice they face within the bounds of uncertainty. If at the heart of it, journalism is still about bringing the powerful to account, then the beneficiaries of patriarchy are indeed powerful, and have indeed benefited from the impunity they have in matters of sexual violence. The least we can do is our jobs.

The writer is a breaking news correspondent for Politico Europe @saimsaeed847

The second principle, whose application has been made de rigueur thanks to the work done by activists everywhere, is to believe the victims of gender violence as a point of departure. The underlying acknowledgement is that a system (especially in Pakistan) designed to benefit men at women’s expense makes it difficult at every step for a woman to seek justice against her attacker. The first hurdle in her way is our attitude (You were asking for it. You should take it as a compliment), then there are the laws (Pakistan’s notorious Hudood Ordinance, to name one), the sluggish and costly process by which guilt or innocence is determined, and finally even if a woman wins a conviction against her attacker, a shame-based society such as ours would still punish the woman for being so brazen as to be vocal about her experience. Indeed, at this stage we often find women raking the victim over the coals for speaking out.

The court of public opinion is different from state courts. It would be disingenuous and even harmful to determine guilt or innocence without being privy to all the evidence. The presumption of guilt is tantamount to defamation

Outside Pakistan though, societies are incrementally moving towards taking accusations of sexual harassment seriously, as a slew of famous personalities such as Bill Cosby, Woody Allen, Roger Ailes, and American president Donald Trump have seen when they came under intense media scrutiny or faced legal proceedings and punishment.

Cases of sexual harassment throw up a peculiar incongruity. How can the media assume the innocence of the accused while believing the victim simultaneously? As humans, we generally like to order our lives in morally unambiguous terms, inhabit a world with good guys and bad guys, and rarely anything in between. And thus, when someone accuses someone else of sexual harassment, most of us want to believe the victim as innocent, and demonize the perpetrator. The problem is, neither course of action may actually be based on the truth, and even if it is, we cannot know for sure.

Take the recent case of journalist Zubaria Jan accusing her former boss Salman Masood of sexual harassment in a blog post. (She also accused him of being behind the Twitter account @Saroor Ijaz, but the validity of that accusation is not the subject of this article.) The screenshots that Zubaria Jan takes of her Whatsapp and Twitter conversations with the person who she alleges is Salman Masood do not incriminate Masood, but they do not excuse him either. Masood denied the accusations on Twitter, calling them “frivolous” and “malicious”.

Without witnesses or evidence, it is impossible to know with certainty what actually took place, but in their absence, there are still some decisions to make after someone chooses to go public with the matter. The first decision perhaps lay with Zubaria Jan on how to deal with the complaint(s) she had. Ideally organisations should have in-house confidential sexual harassment committees that tackle cases such as hers. Another way of handling them is for the aggrieved party to write to the editor.

But for now, and given what little we know, one question to ask is whether journalists should reserve judgement until more facts are revealed in such circumstances. How seriously ought the media take Zubaria Jan’s claims without an investigation or independent collection of evidence? Should the media be spurred by a blog post take it upon itself to determine the answers of a sexual harassment case given the absence of formal corporate and/or judicial procedures to address such accusations?

First, it must be acknowledged that while the media has an important role in investigating, analysing and researching information that is sometimes essential to criminal or civil cases, that role is limited. The court of public opinion is different from state courts which is why it would be disingenuous and even harmful to determine guilt or innocence in the media without being able to present all the evidence. The presumption of guilt for someone a court has determined to be innocent is tantamount to defamation, if not necessarily in the legal definition of the word.

When there is no evidence, the media’s judgment on a particular case or individual will always be limited. In Bill O’Reilly’s recent case, it emerged that he settled out of court with his accuser. The settlement is not indicative of O’Reilly’s guilt or innocence. (O’Reilly’s lawyer said, “There is absolutely no basis for any claim of sexual harassment.”) He might have been innocent but perhaps wished not to have his name dragged through the mud. Or he may have been guilty and thought it best to settle discreetly. Either way, the available facts are not enough to determine guilt. That said, determining the guilty party can only be the end result of good journalistic work, and that starts with taking the accuser’s allegations seriously and investigating. Just as one follows up on any tip from a source, a journalist’s job is to dig further, to ask questions of many to people, to find evidence—documents, recordings, photographs—that can help determine what really happened.

Whatever the journal or the journalist’s political leanings and biases, we are all required to verify and cross-check what we’ve been told, and at the same time maintain the trust of our sources. It’s a difficult position to maintain, as the catastrophe that was the Rolling Stone’s story about rape on university campuses demonstrated. In their case, solely believing the victim ‘Jackie’ as she was called, and not others, meant that in the end the story was shredded when put under actual scrutiny by a Columbia School of Journalism investigation. The writer meant to be supportive and ethical in her support for the victim, but it was bad journalism, and may have caused more damage to rape culture on college campuses than champion their cause.

‘Trust, but verify’ might be an adage as useful to journalists as it was to the Cold War. It is fundamental not to dismiss any accusations of sexual violence offhand, and as with all other stories, journalists ought to investigate those accusations to reach as close to the truth as they can. Although it is entirely understandable when journalists fail to do so, I’d much rather it be because of an absence of evidence than structural sexism.

In Pakistan, the terrain is even more difficult. In the absence of a robust legal system or in-house structures to deal with harassment in office settings (especially when it comes to freelance professionals), there is little faith that victims of gender violence will get the justice they seek. In such cases journalists can assist the accused in producing the evidence they need, and give a voice to the injustice they face within the bounds of uncertainty. If at the heart of it, journalism is still about bringing the powerful to account, then the beneficiaries of patriarchy are indeed powerful, and have indeed benefited from the impunity they have in matters of sexual violence. The least we can do is our jobs.

The writer is a breaking news correspondent for Politico Europe @saimsaeed847