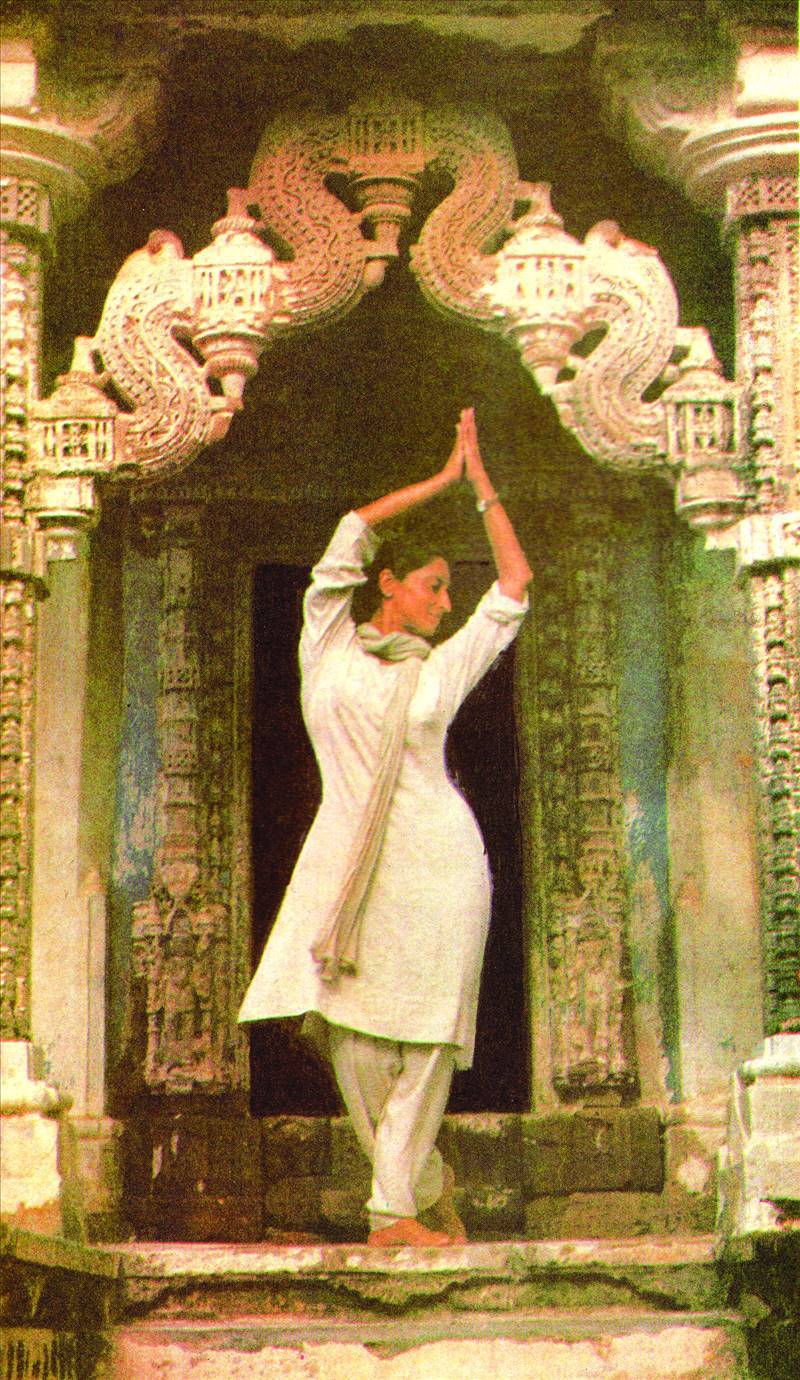

Sheema Kermani has lived the life of a warrior despite belonging to the Arts, which is usually associated with extreme sensitivity. Words may fall short of listing the accolades which Kermani has to her name, but what is essential to know is that she has striven hard to spread peace and tolerance in a society smitten by extremism of all kinds, and she has done so by delving deep into the Indian Subcontinent’s history in order to make people realize that theirs is a land of art and culture. The Friday Times caught up with the classical dancer, instructor, women’s rights activist and theatre performer to ask her some questions.

Muhammad Ali: Do you feel tired at times, for yours is a journey full of hurdles? What keeps you moving?

Sheema Kermani: My belief in the truth and beauty of my art is what keeps me going. I know that whenever someone sets out to do something which is not the norm, or something that is different and perhaps also not totally acceptable, hurdles and obstacles are bound to come in the way. However, I have always been a fighter and a rebel, as a result of which I am quite used to these hurdles. In fact, there are times when I feel that it is precisely the challenges that I enjoy. Besides, my training has been a political one and through my readings of history, I have understood how to cope with these challenges. I am convinced that dance is important for a civilised, inclusive and tolerant society.

M.A.: Are you still hopeful that patriarchy and misogyny will come to an end? What future do you see of Pakistan?

S.K.: Yes, I believe that patriarchy and misogyny will definitely come to an end – they have to come to an end for the society to move forward, to advance and to develop. No society can be called developed or civilised until misogyny and patriarchy exist. A society that does not provide equal status and equal rights to all its citizens is totally unacceptable. Even the constitution of Pakistan claims to provide equal rights to all its citizens and not discriminate on the basis of sex, religion or class. But unfortunately, no government to date has been concerned about these issues, which is the tragedy of our country. Unless and until women and other marginalised people can live up to their full potential, there cannot be a just and moral society. I think that the future of Pakistan hangs precisely on these issues. When the state of Pakistan, the ruling establishment and the governments decide to move away from religious terrorism, obscurantism and fundamentalism and create a peaceful environment instead, then we can begin to see a future – and if this is not done, then I really do not see a future for Pakistan.

M.A.: It is said that dance movements are there in nature. What is your take on this?

S.K.:Of course! I have always held that dance is inherently within us and all around us. How did dance come about? When human beings alighted on the planet we call earth, dance came with them. Perhaps, it existed even before humans, because the wind, the water, the animals, all dance; they all have their own rhythm (taal) and their own melody (sur). As soon as a child is born, the first thing that the doctor checks is the pulse of the child, and then the sound of the child - this is the rhythm and the melody inherent in the human being. If the child does not cry or does not move its limbs, it becomes a matter of concern. Then when human beings started cultivating the land, they performed collective labour activity, moving in a collective rhythm - this collective movement/labour activity is what we now call our ‘folk dances’. These were also related to nature in the sense that lack of scientific knowledge led the primitive human to sing and dance to address or appease the unknown supernatural forces of nature. This was the origin of dance - totally related to human beings, their needs, their aspirations, their emotions and their desires. Dance was a means of social communication in pre-state societies, a part of the ritual for coordinating a community’s activities. Thus, dance was the basic mechanism for conveying education and knowledge to the adult members of the community from one generation to the next. Over time, it was the accumulated knowledge and experience of the human mind, and highly evolved methods of body and mind training that moulded and created the dances that we now place under the category of ‘classical dance’. It is because we dancers are trained in so many complex aspects that we become empowered to tackle any aspect of communication - verbal, non-verbal and also the communication required for social change.

M.A.: How is story telling linked to classical dance?

S.K.: All classical dance is about storytelling. When people were not literate, they would pass on their legends, their histories, their myths and stories about their heroes and heroines through oral tradition. For these narrations, they would use all their means, i.e. voice, body and facial expression, movement and hand gestures. They would sing, they would become different characters, they would narrate and they would of course act. Therefore, dance is the mother of all performing arts because it incorporates all of them within it.

M.A.: You performed in classical serials like Marvi and Chand Grahan but we don’t see you in dramas anymore. Why is that so?

S.K.: Yes, I have performed in many TV serials but this was some time ago. I am very interested in working in TV plays but I do not want to work in any drama where women are demeaned and shown as vulgar, obscene and evil all the time. I have been given a few scripts recently but the character is always of an extremely cruel and evil woman who exploits other women and men, or of someone who is to be pitied and is ready to face all kinds of violence by the husband or family just to keep her marriage going. I feel that this attitude towards women by our media is extremely harmful and infuses more toxic masculinity and patriarchy in our society. I believe that art and artists must play a positive and educational role in our society because the ordinary people follow characters and make them their role models. I do not understand why our stories cannot be about the ordinary brave women, the peasants, the workers who struggle to work and spend their lives with honesty and dignity as independent, working women. These are the women who should be our role models; who live in low-income areas and strive to educate their children and run their homes and are often the sole bread earners and head of their families. I myself have many stories and many productions that I have made but no TV channel is willing to show these. Through Tehrik-e-Niswan, we have also made many motivational and inspirational videos which we give free of cost to TV channels but they are not willing to run even those, as their sole purpose is to attain monetary profit. Few people know that when a channel is given the license to broadcast content, it has to commit to a certain amount of time for educational programmes. Unfortunately, in Pakistan, no channel airs classical dance, classical music or any such intellectual or educative programmes.

M.A.: What kinds of books attract you?

S.K.:I read all kinds of books, both fiction as well as non-fiction. I love reading autobiographies of outstanding women and artists. I am also very interested in art, culture and history, especially of the Subcontinent. I have just completed my thesis for MPhil and the topic was “The Search for a New Cultural Identity of Pakistan” and for this purpose I had to read a lot.

M.A.: Does your art also help you heal during bad times?

S.K.: Yes, definitely! I believe that my art is what heals me in times of stress and depression. Art works as a therapy and is often recommended by doctors to their patients. Scientists are turning to dance because it is a multifaceted activity that can help them. Educators and even parents demystify how the brain coordinates with the body to perform complex, precise movements which express emotion and convey meaning. Dancers possess an extraordinary skill set: coordination of limbs, posture, balance, gesture, facial expression, perception, and action in sequences that create meaning in time and space. Dance is a language of physical exercise that sparks new brain cells (neuro-genesis) and their connections. These connections are responsible for acquiring knowledge and thinking. Dancing stimulates the release of the brain-derived protein, neuro-tropic factor that promotes the growth, maintenance and plasticity of neurons necessary for learning and memory. Through dance, one can learn about academics and about oneself: including gender, ethnic and regional identities. Moreover, dance is a means to help us improve our mood and cope with stress that can motivate concentration and learning.

M.A.: Tell us about the illustrated book based on your life that has recently been published. Where can we easily get it?

S.K.: Oxford University Press has published a series of graphic stories about the lives and work of prominent Pakistani citizens. This series basically strives to pass on motivational stories to young people. It is a great honour for me that they chose me in their list of outstanding personalities of Pakistan. The book is written by Rumana Hussain and illustrated by Naila Ahmed. I believe it is easily available at all the outlets and shops of Oxford University Press.

M.A.: Which other classical dancers from Pakistan do you admire?

S.K.: Well, most of the young dancers in Pakistan have been taught by me because for over a decade, Pakistan had no dancers or dance teachers. When General Zia-ul-Haq imposed Martial Law and introduced his so-called Islamic laws, he disbanded the Arts Councils, the National Performing Arts Group, banned dancing by women on stage and implicitly termed dance as “un-Islamic”. At that time, all the dancers left the country but I decided to stay on. I continued to perform and teach and have been doing so since then. My guru, Mr. Ghanshyam was the dancer I admired the most. All that I am, I have learned from him. He was an extra-ordinary dancer and an extra-ordinary human being. The most important thing for an artist is to be pure, honest and generous. This is what I learned from him.

M.A.: How do you recharge yourself when faced with hatred and violence?

S.K.: I have faced many difficult times, even death threats and persecution but I know that what I do is profound, sacred, beautiful and about love. I have total conviction about the beauty of this art form. I believe that dance is not merely a recreation, even though dance as a recreation is important; dance is also not just an art form, even though dance as a great and profound art form is important, but what I believe is that dance is life and living. A society that does not have dance is a dead society! For me, dance is a discipline that covers most, if not all, facets of human education and creates a well-rounded personality. It enables a better understanding of a variety of apparently strictly academic disciplines; from history and geography to grammar and mathematics, helping develop all those parameters that result in a person being called an educated human being. We must teach these arts to our youth to move them away from violence and gun culture. Teach them, practise them and include them in the formal learning curricula of schools and colleges so that the goals of a civil society can be brought nearer. We must teach dance to our girls so that they find confidence and dignity in their bodies. Only then we will be on the right track because, as Albert Einstein said famously, “While Logic will get you from A to B, imagination will take you everywhere.” When I am involved in my creative work, I become strong, I get courage and I become fearless. This is why my art is so important for me. I can never forget the day in December 1988 when people had voted for their new representatives after twelve long years of cultural repression of General Zia-ul-Haq’s military dictatorship, the streets of Karachi were jam-packed with people dancing in the streets. Yes, dancing! And dancing with joy - people of all ages and all classes expressing their freedom and their liberty in rhythmic movement, in dance! As a Pakistani female, theatre practitioner, cultural activist and a practicing classical dancer, I have often had to explain my choice of the form of dance that I practice. I have been accused of choosing to practice what are considered outright Hindu dance forms (Bharatanatyam and Odissi), as opposed to the historical narrative that is provided for Kathak as being associated primarily with the Muslim Mughal Empire. I have always disagreed with this whirlwind historicization of Kathak. I argue that it is impossible to compartmentalise an art form in terms of aesthetics, religious practice, physical technique, etc. The very impossibility of compartmentalising the dance demonstrates the need to examine further its constitutive parts, and why these are sometimes emphasised, sometimes downplayed. As long as we live, as long as we breathe, as long as we are alive, we will continue to dance no matter what, because dance is about being alive, dance is life!

Muhammad Ali is an M.Phil scholar and a former visiting lecturer at GCU, Lahore. His interest lies in indigenous literature, the specific research areas being Partition novel, Environmental Literature emerging from South Asia and classical and contemporary Pakistani television drama. His research on Sahira Kazmi’s “Zaib un Nisa” which was a part of his graduation thesis has been presented on various platforms including Olomopolo Media. This interview is a part of a series of interviews in which various Pakistani celebrities including writers, actors and directors will be asked questions regarding their professional work. The writer can be reached at m.ali_aquarius85@yahoo.com.

***

Muhammad Ali: Do you feel tired at times, for yours is a journey full of hurdles? What keeps you moving?

Sheema Kermani: My belief in the truth and beauty of my art is what keeps me going. I know that whenever someone sets out to do something which is not the norm, or something that is different and perhaps also not totally acceptable, hurdles and obstacles are bound to come in the way. However, I have always been a fighter and a rebel, as a result of which I am quite used to these hurdles. In fact, there are times when I feel that it is precisely the challenges that I enjoy. Besides, my training has been a political one and through my readings of history, I have understood how to cope with these challenges. I am convinced that dance is important for a civilised, inclusive and tolerant society.

M.A.: Are you still hopeful that patriarchy and misogyny will come to an end? What future do you see of Pakistan?

S.K.: Yes, I believe that patriarchy and misogyny will definitely come to an end – they have to come to an end for the society to move forward, to advance and to develop. No society can be called developed or civilised until misogyny and patriarchy exist. A society that does not provide equal status and equal rights to all its citizens is totally unacceptable. Even the constitution of Pakistan claims to provide equal rights to all its citizens and not discriminate on the basis of sex, religion or class. But unfortunately, no government to date has been concerned about these issues, which is the tragedy of our country. Unless and until women and other marginalised people can live up to their full potential, there cannot be a just and moral society. I think that the future of Pakistan hangs precisely on these issues. When the state of Pakistan, the ruling establishment and the governments decide to move away from religious terrorism, obscurantism and fundamentalism and create a peaceful environment instead, then we can begin to see a future – and if this is not done, then I really do not see a future for Pakistan.

M.A.: It is said that dance movements are there in nature. What is your take on this?

S.K.:Of course! I have always held that dance is inherently within us and all around us. How did dance come about? When human beings alighted on the planet we call earth, dance came with them. Perhaps, it existed even before humans, because the wind, the water, the animals, all dance; they all have their own rhythm (taal) and their own melody (sur). As soon as a child is born, the first thing that the doctor checks is the pulse of the child, and then the sound of the child - this is the rhythm and the melody inherent in the human being. If the child does not cry or does not move its limbs, it becomes a matter of concern. Then when human beings started cultivating the land, they performed collective labour activity, moving in a collective rhythm - this collective movement/labour activity is what we now call our ‘folk dances’. These were also related to nature in the sense that lack of scientific knowledge led the primitive human to sing and dance to address or appease the unknown supernatural forces of nature. This was the origin of dance - totally related to human beings, their needs, their aspirations, their emotions and their desires. Dance was a means of social communication in pre-state societies, a part of the ritual for coordinating a community’s activities. Thus, dance was the basic mechanism for conveying education and knowledge to the adult members of the community from one generation to the next. Over time, it was the accumulated knowledge and experience of the human mind, and highly evolved methods of body and mind training that moulded and created the dances that we now place under the category of ‘classical dance’. It is because we dancers are trained in so many complex aspects that we become empowered to tackle any aspect of communication - verbal, non-verbal and also the communication required for social change.

“I have faced many difficult times, even death threats and persecution but I know that what I do is profound, sacred, beautiful and about love”

M.A.: How is story telling linked to classical dance?

S.K.: All classical dance is about storytelling. When people were not literate, they would pass on their legends, their histories, their myths and stories about their heroes and heroines through oral tradition. For these narrations, they would use all their means, i.e. voice, body and facial expression, movement and hand gestures. They would sing, they would become different characters, they would narrate and they would of course act. Therefore, dance is the mother of all performing arts because it incorporates all of them within it.

M.A.: You performed in classical serials like Marvi and Chand Grahan but we don’t see you in dramas anymore. Why is that so?

S.K.: Yes, I have performed in many TV serials but this was some time ago. I am very interested in working in TV plays but I do not want to work in any drama where women are demeaned and shown as vulgar, obscene and evil all the time. I have been given a few scripts recently but the character is always of an extremely cruel and evil woman who exploits other women and men, or of someone who is to be pitied and is ready to face all kinds of violence by the husband or family just to keep her marriage going. I feel that this attitude towards women by our media is extremely harmful and infuses more toxic masculinity and patriarchy in our society. I believe that art and artists must play a positive and educational role in our society because the ordinary people follow characters and make them their role models. I do not understand why our stories cannot be about the ordinary brave women, the peasants, the workers who struggle to work and spend their lives with honesty and dignity as independent, working women. These are the women who should be our role models; who live in low-income areas and strive to educate their children and run their homes and are often the sole bread earners and head of their families. I myself have many stories and many productions that I have made but no TV channel is willing to show these. Through Tehrik-e-Niswan, we have also made many motivational and inspirational videos which we give free of cost to TV channels but they are not willing to run even those, as their sole purpose is to attain monetary profit. Few people know that when a channel is given the license to broadcast content, it has to commit to a certain amount of time for educational programmes. Unfortunately, in Pakistan, no channel airs classical dance, classical music or any such intellectual or educative programmes.

M.A.: What kinds of books attract you?

S.K.:I read all kinds of books, both fiction as well as non-fiction. I love reading autobiographies of outstanding women and artists. I am also very interested in art, culture and history, especially of the Subcontinent. I have just completed my thesis for MPhil and the topic was “The Search for a New Cultural Identity of Pakistan” and for this purpose I had to read a lot.

M.A.: Does your art also help you heal during bad times?

S.K.: Yes, definitely! I believe that my art is what heals me in times of stress and depression. Art works as a therapy and is often recommended by doctors to their patients. Scientists are turning to dance because it is a multifaceted activity that can help them. Educators and even parents demystify how the brain coordinates with the body to perform complex, precise movements which express emotion and convey meaning. Dancers possess an extraordinary skill set: coordination of limbs, posture, balance, gesture, facial expression, perception, and action in sequences that create meaning in time and space. Dance is a language of physical exercise that sparks new brain cells (neuro-genesis) and their connections. These connections are responsible for acquiring knowledge and thinking. Dancing stimulates the release of the brain-derived protein, neuro-tropic factor that promotes the growth, maintenance and plasticity of neurons necessary for learning and memory. Through dance, one can learn about academics and about oneself: including gender, ethnic and regional identities. Moreover, dance is a means to help us improve our mood and cope with stress that can motivate concentration and learning.

M.A.: Tell us about the illustrated book based on your life that has recently been published. Where can we easily get it?

S.K.: Oxford University Press has published a series of graphic stories about the lives and work of prominent Pakistani citizens. This series basically strives to pass on motivational stories to young people. It is a great honour for me that they chose me in their list of outstanding personalities of Pakistan. The book is written by Rumana Hussain and illustrated by Naila Ahmed. I believe it is easily available at all the outlets and shops of Oxford University Press.

M.A.: Which other classical dancers from Pakistan do you admire?

S.K.: Well, most of the young dancers in Pakistan have been taught by me because for over a decade, Pakistan had no dancers or dance teachers. When General Zia-ul-Haq imposed Martial Law and introduced his so-called Islamic laws, he disbanded the Arts Councils, the National Performing Arts Group, banned dancing by women on stage and implicitly termed dance as “un-Islamic”. At that time, all the dancers left the country but I decided to stay on. I continued to perform and teach and have been doing so since then. My guru, Mr. Ghanshyam was the dancer I admired the most. All that I am, I have learned from him. He was an extra-ordinary dancer and an extra-ordinary human being. The most important thing for an artist is to be pure, honest and generous. This is what I learned from him.

M.A.: How do you recharge yourself when faced with hatred and violence?

S.K.: I have faced many difficult times, even death threats and persecution but I know that what I do is profound, sacred, beautiful and about love. I have total conviction about the beauty of this art form. I believe that dance is not merely a recreation, even though dance as a recreation is important; dance is also not just an art form, even though dance as a great and profound art form is important, but what I believe is that dance is life and living. A society that does not have dance is a dead society! For me, dance is a discipline that covers most, if not all, facets of human education and creates a well-rounded personality. It enables a better understanding of a variety of apparently strictly academic disciplines; from history and geography to grammar and mathematics, helping develop all those parameters that result in a person being called an educated human being. We must teach these arts to our youth to move them away from violence and gun culture. Teach them, practise them and include them in the formal learning curricula of schools and colleges so that the goals of a civil society can be brought nearer. We must teach dance to our girls so that they find confidence and dignity in their bodies. Only then we will be on the right track because, as Albert Einstein said famously, “While Logic will get you from A to B, imagination will take you everywhere.” When I am involved in my creative work, I become strong, I get courage and I become fearless. This is why my art is so important for me. I can never forget the day in December 1988 when people had voted for their new representatives after twelve long years of cultural repression of General Zia-ul-Haq’s military dictatorship, the streets of Karachi were jam-packed with people dancing in the streets. Yes, dancing! And dancing with joy - people of all ages and all classes expressing their freedom and their liberty in rhythmic movement, in dance! As a Pakistani female, theatre practitioner, cultural activist and a practicing classical dancer, I have often had to explain my choice of the form of dance that I practice. I have been accused of choosing to practice what are considered outright Hindu dance forms (Bharatanatyam and Odissi), as opposed to the historical narrative that is provided for Kathak as being associated primarily with the Muslim Mughal Empire. I have always disagreed with this whirlwind historicization of Kathak. I argue that it is impossible to compartmentalise an art form in terms of aesthetics, religious practice, physical technique, etc. The very impossibility of compartmentalising the dance demonstrates the need to examine further its constitutive parts, and why these are sometimes emphasised, sometimes downplayed. As long as we live, as long as we breathe, as long as we are alive, we will continue to dance no matter what, because dance is about being alive, dance is life!

Muhammad Ali is an M.Phil scholar and a former visiting lecturer at GCU, Lahore. His interest lies in indigenous literature, the specific research areas being Partition novel, Environmental Literature emerging from South Asia and classical and contemporary Pakistani television drama. His research on Sahira Kazmi’s “Zaib un Nisa” which was a part of his graduation thesis has been presented on various platforms including Olomopolo Media. This interview is a part of a series of interviews in which various Pakistani celebrities including writers, actors and directors will be asked questions regarding their professional work. The writer can be reached at m.ali_aquarius85@yahoo.com.