In October, Parliament passed an anti-honour killing law, ostensibly to correct loopholes in the law that allowed family members to “forgive” perpetrators. More than four million residents of the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (Fata), however, have been completely absent from this discussion, both on the floor of Parliament as well as on our television screens.

Murders in the name of “honour” are rampant in Fata. Also common are killings for other reasons that are later “confessed” to be in the name of “honour”. This just benefits from the widespread acceptance of such murders in deference to custom or “riwaj”.

One such example is the murder of Fazeelat and her husband Said Alam’s uncle Kher Ullah, in Landi Kotal, Khyber Agency, Fata, in November 2015. Said Alam’s brothers killed Fazeelat and Kher Ullah because of a business dispute. The accused were arrested and later “confessed” that they had killed the victims “in the name of honour” to protect their reputation in society. Said Alam denied allegations that his deceased wife was “immoral” or “of bad character”. According to him, the murders were clearly a result of a business deal gone sour.

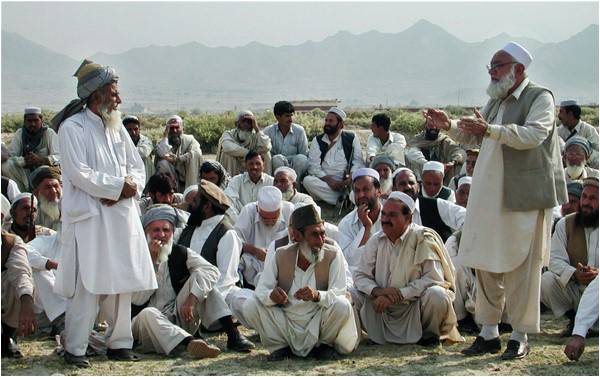

As per the laws in Fata, this case was not decided by an independent court, but a jirga or council of elders appointed by the Assistant Political Agent of Landi Kotal. The jirga held that “the accused under the local riwaj were obliged to kill them (Fazeelat and Kher Ullah), as it was the matter of their honour”. According to members of the jirga, “the murder of the deceased victims is justified, even without the willingness of the husband, as per riwaj”. The Assistant Political Agent upheld the jirga’s ruling in June 2016.

Incidentally, in the case file there was also a letter from a sitting MNA, who wrote to the APA of Landi Kotal in support of the accused, requesting the court of the APA to decide the case on the basis of riwaj as the murder was committed “in the name of honour”. The MNA is a member of the same assembly that passed an anti-honour killing law in October.

In most cases, any hopes for justice and accountability would have ended here. But in Fazeelat’s case, media and civil society activism helped achieve what is nothing short of a miracle. The Human Rights Commission of Pakistan intervened by condemning the murders and the illegal order of the APA in a press release. Journalists and other activists also rallied behind the HRCP’s demand to prevent “riwaj” from being used as a justification for murder.

On July 7, 2016, an appeal was filed before the FCR Commissioner, Peshawar. In a scathing judgment, the Commissioner struck down the orders of the Assistant Political Agent of Landi Kotal and ordered a fresh trial of the case. Not only did he call into question the supposed motive of “honour” that the accused were using to justify the killings, he also expressly stated that even if the murders were “honour killings”, the perpetrators must be held accountable for their actions and “riwaj” was no reason for them to evade punishment. He also observed that if murders “in the name of honour” were condoned because of “riwaj”, then “any person may resort to murder, confess it as honour killing and go scot-free”.

Justice may eventually be served in this particular case because of the FCR Commissioner’s rare progressive order, but it nevertheless highlights the inherent problems with the criminal justice system in Fata. The Political Agents and Assistant Political Agents enjoy executive as well as judicial powers, and appeals against their orders are heard by the “court” of a Commissioner (also an executive office). While in “mainstream” Pakistan the judiciary is independent of the executive, in Fata, the two are still very much yoked, making a mockery of the concept of a “fair trial”. This lack of separation also makes them vulnerable to external pressures and influences, calling into question their competence, independence and impartiality.

To make matters worse, high courts and the Supreme Court, responsible for safeguarding fundamental rights under the Constitution, have no jurisdiction in Fata. Even if orders of Fata’s “courts” are incompatible with fundamental rights, there are no avenues to challenge them. It is therefore a longstanding demand of the people of Fata that the Peshawar High Court’s jurisdiction should be extended to the region.

There is an active debate on the future of Fata—possibly its merger with Khyber Pakhtunkhwa or the creation of Fata as an autonomous province. One thing is clear: Fata reforms must not be delayed further and human rights must remain a priority in the reforms. It is time residents of Fata had equal rights and protections as their compatriots in other parts of the country.

The writer is lawyer and can be reached at irshadahmadadvocate@gmail.com

Murders in the name of “honour” are rampant in Fata. Also common are killings for other reasons that are later “confessed” to be in the name of “honour”. This just benefits from the widespread acceptance of such murders in deference to custom or “riwaj”.

One such example is the murder of Fazeelat and her husband Said Alam’s uncle Kher Ullah, in Landi Kotal, Khyber Agency, Fata, in November 2015. Said Alam’s brothers killed Fazeelat and Kher Ullah because of a business dispute. The accused were arrested and later “confessed” that they had killed the victims “in the name of honour” to protect their reputation in society. Said Alam denied allegations that his deceased wife was “immoral” or “of bad character”. According to him, the murders were clearly a result of a business deal gone sour.

As per the laws in Fata, this case was not decided by an independent court, but a jirga or council of elders appointed by the Assistant Political Agent of Landi Kotal. The jirga held that “the accused under the local riwaj were obliged to kill them (Fazeelat and Kher Ullah), as it was the matter of their honour”. According to members of the jirga, “the murder of the deceased victims is justified, even without the willingness of the husband, as per riwaj”. The Assistant Political Agent upheld the jirga’s ruling in June 2016.

Incidentally, in the case file there was also a letter from a sitting MNA, who wrote to the APA of Landi Kotal in support of the accused, requesting the court of the APA to decide the case on the basis of riwaj as the murder was committed “in the name of honour”. The MNA is a member of the same assembly that passed an anti-honour killing law in October.

In most cases, any hopes for justice and accountability would have ended here. But in Fazeelat’s case, media and civil society activism helped achieve what is nothing short of a miracle. The Human Rights Commission of Pakistan intervened by condemning the murders and the illegal order of the APA in a press release. Journalists and other activists also rallied behind the HRCP’s demand to prevent “riwaj” from being used as a justification for murder.

On July 7, 2016, an appeal was filed before the FCR Commissioner, Peshawar. In a scathing judgment, the Commissioner struck down the orders of the Assistant Political Agent of Landi Kotal and ordered a fresh trial of the case. Not only did he call into question the supposed motive of “honour” that the accused were using to justify the killings, he also expressly stated that even if the murders were “honour killings”, the perpetrators must be held accountable for their actions and “riwaj” was no reason for them to evade punishment. He also observed that if murders “in the name of honour” were condoned because of “riwaj”, then “any person may resort to murder, confess it as honour killing and go scot-free”.

Justice may eventually be served in this particular case because of the FCR Commissioner’s rare progressive order, but it nevertheless highlights the inherent problems with the criminal justice system in Fata. The Political Agents and Assistant Political Agents enjoy executive as well as judicial powers, and appeals against their orders are heard by the “court” of a Commissioner (also an executive office). While in “mainstream” Pakistan the judiciary is independent of the executive, in Fata, the two are still very much yoked, making a mockery of the concept of a “fair trial”. This lack of separation also makes them vulnerable to external pressures and influences, calling into question their competence, independence and impartiality.

To make matters worse, high courts and the Supreme Court, responsible for safeguarding fundamental rights under the Constitution, have no jurisdiction in Fata. Even if orders of Fata’s “courts” are incompatible with fundamental rights, there are no avenues to challenge them. It is therefore a longstanding demand of the people of Fata that the Peshawar High Court’s jurisdiction should be extended to the region.

There is an active debate on the future of Fata—possibly its merger with Khyber Pakhtunkhwa or the creation of Fata as an autonomous province. One thing is clear: Fata reforms must not be delayed further and human rights must remain a priority in the reforms. It is time residents of Fata had equal rights and protections as their compatriots in other parts of the country.

The writer is lawyer and can be reached at irshadahmadadvocate@gmail.com