The marvel that is Pakistan will never fit into one personality cult. It will never produce a singular version of a model Pakistani. We have among us those with more liberal and secular portrayals, and those that resonate well within an Islamic federation.

But, irrespective of which side of the divide they stand, where do they derive their ideas of Pakistan from and who are ‘they’? Do they ever have the moral right or responsibility to direct these historical representations or misrepresentations? Hasn’t the 21st century’s political and social landscape stultified the need to entrench young minds with pre-existing biases and limit their access to knowledge?

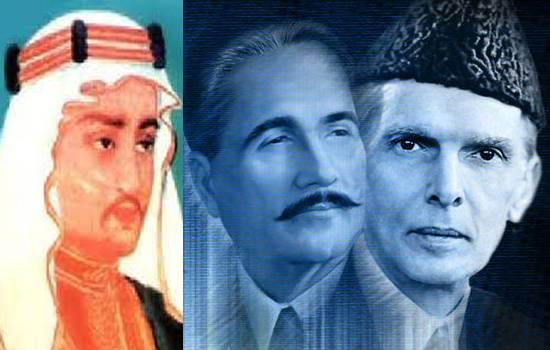

One major historical example of this misrepresentation is the legend of the Muslim conqueror who docked at the shores of Sindh in 712 CE -- Muhammad Bin Qasim. It is a teleological explanation to claim that Qasim fought Raja Dahir in all his might to introduce Islam to the region, let alone preach it. This misconception stands to be the single biggest reason for his commemoration in history. Our history however did not start from the Battle of Aror, as is taught in most schools today in Pakistan. We were here long before that with our rituals, cultures, festivities, traditions, and civilisations. One among many others was the Gandhara civilisation. Then why is it that a 17-year-old invader, who attacked merely as a result of a pirate raid off of the Sindh Coast and left immediately afterwards, is perched atop history books taught in schools?

The leaders of the freedom movement could neither be saved from being butchered by oversimplified narratives. For instance, Quaid-e-Azam Muhammad Ali Jinnah, acclaimed for his struggle in the making of Pakistan has been drawn out in various lights – in sherwani with a Jinnah cap and in a three-piece suit sitting next to a dog with a cigar. Such confusing depictions point out the facile approach taken by those who propagate this sort of history. To present Jinnah as a digestible symbol of identity, they ignore the complex nature of his personality. They present him in black and white, no grey.

Allama Iqbal suffers a similar fate. He was a great poet, thinker and philosopher, and must be accredited for his pivotal role in the realisation of his dream of ‘Pakistan’. Although he was responsible for alchemising the Muslim thought and protecting it from ideological bankruptcy, he never inherently believed in nationalism. A verse from his ever-green Bang-e-Dara translates to:

Country is the biggest among these new gods!

What is its shirt is the shroud of Deen (Religion)

Clearly, he condemned the idea of national identity. He believed in the idea of ummah that transcends nations and borders. Although ambivalent, this idea of Iqbal is not taught or referred to in Pakistan.

Iqbal and Jinnah will always be our national heroes. We must recognise that they are more complex than meets the eye. We are perhaps afraid of acknowledging that opposing narratives may challenge the status quo and trigger uncomfortable debates. It is precisely these debates that are likely to generate the multiplicity of ideas essential to this subject, and introduce newer notions that challenge the mainstream thought.

These were only a few examples from a history that begs dissent. History is not only there to be liked or disliked. It is not there to serve as an instrument of deference. It is not there to be uncritically believed in, especially when there is a flagrant disregard of the letter and spirit of historical verity. It is there to be learnt from, to be critical of, to espouse ideas and concepts that our predecessors could not.

The writer is a Law student at the London School of Economics and Political Science.

But, irrespective of which side of the divide they stand, where do they derive their ideas of Pakistan from and who are ‘they’? Do they ever have the moral right or responsibility to direct these historical representations or misrepresentations? Hasn’t the 21st century’s political and social landscape stultified the need to entrench young minds with pre-existing biases and limit their access to knowledge?

One major historical example of this misrepresentation is the legend of the Muslim conqueror who docked at the shores of Sindh in 712 CE -- Muhammad Bin Qasim. It is a teleological explanation to claim that Qasim fought Raja Dahir in all his might to introduce Islam to the region, let alone preach it. This misconception stands to be the single biggest reason for his commemoration in history. Our history however did not start from the Battle of Aror, as is taught in most schools today in Pakistan. We were here long before that with our rituals, cultures, festivities, traditions, and civilisations. One among many others was the Gandhara civilisation. Then why is it that a 17-year-old invader, who attacked merely as a result of a pirate raid off of the Sindh Coast and left immediately afterwards, is perched atop history books taught in schools?

It is a teleological explanation to claim that Muhammad Bin Qasim fought Raja Dahir in all his might to introduce Islam to the region, let alone preach it.

The leaders of the freedom movement could neither be saved from being butchered by oversimplified narratives. For instance, Quaid-e-Azam Muhammad Ali Jinnah, acclaimed for his struggle in the making of Pakistan has been drawn out in various lights – in sherwani with a Jinnah cap and in a three-piece suit sitting next to a dog with a cigar. Such confusing depictions point out the facile approach taken by those who propagate this sort of history. To present Jinnah as a digestible symbol of identity, they ignore the complex nature of his personality. They present him in black and white, no grey.

Allama Iqbal suffers a similar fate. He was a great poet, thinker and philosopher, and must be accredited for his pivotal role in the realisation of his dream of ‘Pakistan’. Although he was responsible for alchemising the Muslim thought and protecting it from ideological bankruptcy, he never inherently believed in nationalism. A verse from his ever-green Bang-e-Dara translates to:

Country is the biggest among these new gods!

What is its shirt is the shroud of Deen (Religion)

Clearly, he condemned the idea of national identity. He believed in the idea of ummah that transcends nations and borders. Although ambivalent, this idea of Iqbal is not taught or referred to in Pakistan.

History is not only there to be liked or disliked. It is not there to serve as an instrument of deference. It is there to be learnt from, to be critical of, to espouse ideas and concepts that our predecessors could not.

Iqbal and Jinnah will always be our national heroes. We must recognise that they are more complex than meets the eye. We are perhaps afraid of acknowledging that opposing narratives may challenge the status quo and trigger uncomfortable debates. It is precisely these debates that are likely to generate the multiplicity of ideas essential to this subject, and introduce newer notions that challenge the mainstream thought.

These were only a few examples from a history that begs dissent. History is not only there to be liked or disliked. It is not there to serve as an instrument of deference. It is not there to be uncritically believed in, especially when there is a flagrant disregard of the letter and spirit of historical verity. It is there to be learnt from, to be critical of, to espouse ideas and concepts that our predecessors could not.

The writer is a Law student at the London School of Economics and Political Science.