For years, dams have been considered a panacea for Pakistan’s water woes by various experts. They have again emerged in the policy debates as a water management solution. But are they really the solution they are being presented to be?

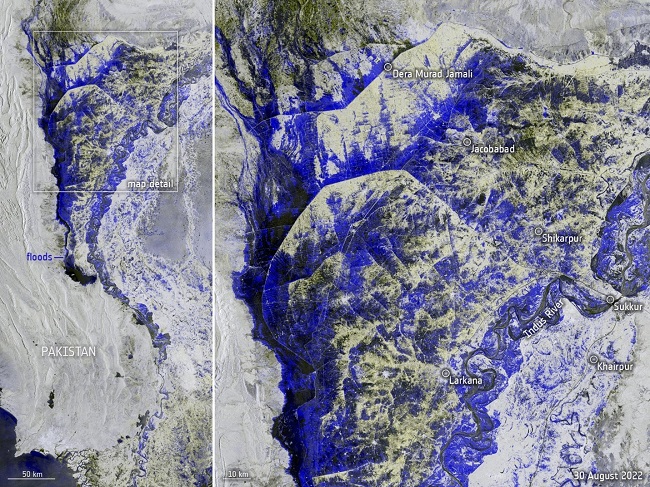

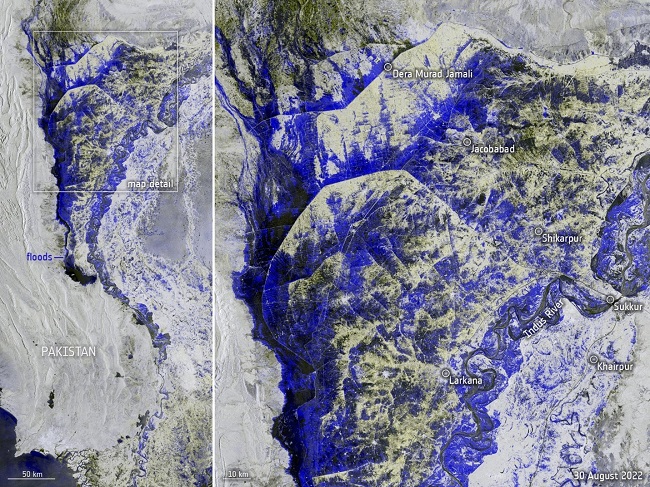

Pakistan has recently experienced yet another climate change-related calamity, only this time disastrous in exponential magnitude with a long-lasting impact. The fatal deluge has rendered around 33 million people homeless with the death toll exceeding 1300 according to NDMA. [R] Submerging one-third of the country as per the satellite data, the floods have decimated the crops and wrecked infrastructure. The raging water has washed away roads, bridges, headworks, small dams and barrages The estimated loss from the floods remains $40 billion [R] and the growth will remain between 1.8% to 2.3%, while providing for people’s needs has meagre prospects in continuing to do so. While the government is presented with a huge challenge of rehabilitating the masses as well as infrastructure, Pakistan needs to rethink its water management policy.

What caused the devastating floods?

Experts are associating several factors with this catastrophe—the major one is the impact of climate change despite the country’s minimal contribution to the global emissions. Another factor is La Niña, an ongoing climate event that brings about warm, drier winter and stronger monsoon conditions. Phenomenal heatwaves right from the onset of the summer season brought about rapid glacial melt and increased air moisture, that contributed to the prolonged monsoon that spawned the highest rainfall in 30 years.

All these factors combined led to flash floods, glacial lake outbursts, and the Indus River’s outflow – creating a tens-of-kilometres-wide long lake. The situation has been exacerbated by the development of structures (homes, pathways, roads) obstructing the floodways. All these factors imply that the country’s surface water needs to be managed.

These floods have underscored how such events can become apocalyptic due to ineffective governance, delayed response and dysfunctional disaster risk management. While the country’s internal inefficacies have come to the forefront, another debate has yet again begun, i.e., dams as a panacea for all the water woes of Pakistan.

Decades passed and dams still remain a policy issue

Dams have dominated Pakistan’s policy landscape for decades. From transboundary governance, water storage to preventing floods, dams have been proposed as an answer to all the water-related problems of the country. Two major dams, the canal system, and barrages were constructed under the Indus Water Treaty to improve water availability and storage capacity of the country. After that, several mega-dams have been proposed. An impassioned narrative revolves around building dams and is considered synonymous with patriotism in a few circles. However, many proposed projects are unacceptable because of their potential harm to the downstream communities. They have become a source of inter-provincial contention. Moreover, recent new research shows that dams might be adding to the problem rather than being the solution. They are harmful to the ecosystem, aquatic life, and adjacent communities. Moreover, they incur strikingly high costs (billions of dollars) not just in construction but also in repair and maintenance. Several studies have found that constructing dams to manage floods is counterproductive. They can intensify floods due to the risk of overflow rather than preventing them, which has been manifested in many flood instances in Pakistan itself. [R] [R] [R]

Besides, research shows that dams have different designs based on their purpose. [R] A storage dam might not be useful in keeping floods at bay. Detention dams (intended to control floods) would not be effective in storing water. Moreover, climate change is rapidly transforming the water flow. Rivers with ample flow today might turn into a slim channel in the future and vice versa. Constructing dams today without knowing whether there will be any water to store in that area tomorrow is counterintuitive. These dams would rather become a cause of floods downstream. Hence, Pakistan needs to think its dams through.

Tapping the groundwater potential

Groundwater is the Cinderella of Pakistan’s water landscape. From provision to sustenance, it does all the work, and yet, is taken for granted. It provides for 90% of water usage in rural Pakistan and accounts for over 50% of agricultural water. Nationally, it supplies 50% of domestic water. [R] Despite its widespread providence, this water source is unregulated and overexploited.

Notably, Pakistan has the world’s fourth largest aquifer. The Indus Basin groundwater stores at least 80 times the volume of water stored in Pakistan’s three mega-dams. However, large-scale abstraction without management and sufficient recharge is depleting groundwater. Contamination from industrial and agricultural waste has impacted water quality drastically. This water source needs to be replenished, and it is relatively easier than erecting giant concrete structures above the surface.

Groundwater recharge through rainwater harvesting, wells, canals and ponds can help replenish this enormous, natural water reservoir. Storing water underground will also help circumvent the water-related climate change impacts, including floods. Above all, this solution is devoid of any controversy, and community engagement will further improve its acceptability and efficacy. It is high time Pakistan resorted to replenishing its aquifers, which will evade the looming groundwater crisis, improve clean water availability, and circumvent floods if done rightly.

That being said, groundwater recharge requires suitability assessments and feasibility studies. Geological surveys and the assessment of the surrounding ecosystem would determine the suitable method of recharge. For different recharge methods, certain conditions need to be met. These technical details need to be sorted out. However, as of now, the policymakers of Pakistan need to bring groundwater into the policy debate and look for ecological solutions. If the current floods have taught us anything, it is to not mess with nature – or it will start messing with us too.

Pakistan has recently experienced yet another climate change-related calamity, only this time disastrous in exponential magnitude with a long-lasting impact. The fatal deluge has rendered around 33 million people homeless with the death toll exceeding 1300 according to NDMA. [R] Submerging one-third of the country as per the satellite data, the floods have decimated the crops and wrecked infrastructure. The raging water has washed away roads, bridges, headworks, small dams and barrages The estimated loss from the floods remains $40 billion [R] and the growth will remain between 1.8% to 2.3%, while providing for people’s needs has meagre prospects in continuing to do so. While the government is presented with a huge challenge of rehabilitating the masses as well as infrastructure, Pakistan needs to rethink its water management policy.

What caused the devastating floods?

Experts are associating several factors with this catastrophe—the major one is the impact of climate change despite the country’s minimal contribution to the global emissions. Another factor is La Niña, an ongoing climate event that brings about warm, drier winter and stronger monsoon conditions. Phenomenal heatwaves right from the onset of the summer season brought about rapid glacial melt and increased air moisture, that contributed to the prolonged monsoon that spawned the highest rainfall in 30 years.

All these factors combined led to flash floods, glacial lake outbursts, and the Indus River’s outflow – creating a tens-of-kilometres-wide long lake. The situation has been exacerbated by the development of structures (homes, pathways, roads) obstructing the floodways. All these factors imply that the country’s surface water needs to be managed.

These floods have underscored how such events can become apocalyptic due to ineffective governance, delayed response and dysfunctional disaster risk management. While the country’s internal inefficacies have come to the forefront, another debate has yet again begun, i.e., dams as a panacea for all the water woes of Pakistan.

Decades passed and dams still remain a policy issue

Dams have dominated Pakistan’s policy landscape for decades. From transboundary governance, water storage to preventing floods, dams have been proposed as an answer to all the water-related problems of the country. Two major dams, the canal system, and barrages were constructed under the Indus Water Treaty to improve water availability and storage capacity of the country. After that, several mega-dams have been proposed. An impassioned narrative revolves around building dams and is considered synonymous with patriotism in a few circles. However, many proposed projects are unacceptable because of their potential harm to the downstream communities. They have become a source of inter-provincial contention. Moreover, recent new research shows that dams might be adding to the problem rather than being the solution. They are harmful to the ecosystem, aquatic life, and adjacent communities. Moreover, they incur strikingly high costs (billions of dollars) not just in construction but also in repair and maintenance. Several studies have found that constructing dams to manage floods is counterproductive. They can intensify floods due to the risk of overflow rather than preventing them, which has been manifested in many flood instances in Pakistan itself. [R] [R] [R]

Besides, research shows that dams have different designs based on their purpose. [R] A storage dam might not be useful in keeping floods at bay. Detention dams (intended to control floods) would not be effective in storing water. Moreover, climate change is rapidly transforming the water flow. Rivers with ample flow today might turn into a slim channel in the future and vice versa. Constructing dams today without knowing whether there will be any water to store in that area tomorrow is counterintuitive. These dams would rather become a cause of floods downstream. Hence, Pakistan needs to think its dams through.

Tapping the groundwater potential

Groundwater is the Cinderella of Pakistan’s water landscape. From provision to sustenance, it does all the work, and yet, is taken for granted. It provides for 90% of water usage in rural Pakistan and accounts for over 50% of agricultural water. Nationally, it supplies 50% of domestic water. [R] Despite its widespread providence, this water source is unregulated and overexploited.

Notably, Pakistan has the world’s fourth largest aquifer. The Indus Basin groundwater stores at least 80 times the volume of water stored in Pakistan’s three mega-dams. However, large-scale abstraction without management and sufficient recharge is depleting groundwater. Contamination from industrial and agricultural waste has impacted water quality drastically. This water source needs to be replenished, and it is relatively easier than erecting giant concrete structures above the surface.

Groundwater recharge through rainwater harvesting, wells, canals and ponds can help replenish this enormous, natural water reservoir. Storing water underground will also help circumvent the water-related climate change impacts, including floods. Above all, this solution is devoid of any controversy, and community engagement will further improve its acceptability and efficacy. It is high time Pakistan resorted to replenishing its aquifers, which will evade the looming groundwater crisis, improve clean water availability, and circumvent floods if done rightly.

That being said, groundwater recharge requires suitability assessments and feasibility studies. Geological surveys and the assessment of the surrounding ecosystem would determine the suitable method of recharge. For different recharge methods, certain conditions need to be met. These technical details need to be sorted out. However, as of now, the policymakers of Pakistan need to bring groundwater into the policy debate and look for ecological solutions. If the current floods have taught us anything, it is to not mess with nature – or it will start messing with us too.