November of 1968 to February of 1969, were perhaps some of the most fiery times in the often troubled history of Pakistan. The four months painted by a revolutionary fervour, surging with the radical energy of the revolutionary and anti-imperialist global movements of the 1960s, these were the months that comprised the anti-Ayub movement. Those were times when East Pakistan and West Pakistan were still one, and the ideas of the Left had a place of considerable importance and influence in the political and intellectual circles of both wings of the country, this is what made possible an anti-dictatorship movement possible at such a popular scale. There were a number of figures which spearheaded the movement and the overall political space of the Left. Though one could talk at length of numerous of those people, but we shall recall today perhaps the most unique individual of the bunch, Maulana Bhashani, or The Red Maualana, or Mao-Lana.

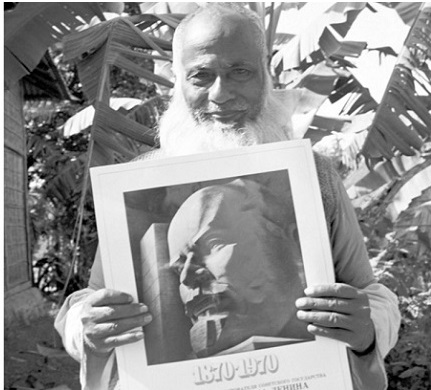

Abdul Hamid Khan Bhashani, popularly known as Maulana Bhashani was born in December 1880 in Dhangra village in Sirajganj, Bengal Presidency. His father was named Shafqat Ali Khan. He passed away in Dhaka at the age of 95 on the 17th of November, 1976.

Bhashani was a progressive whose life-long struggle centered on the betterment of the peasants, the workers and the people. Bhashani was very popular amongst the masses, for his unique approach towards progressive politics. While many communist leaders such as Sajjad Zaheer, the General Secretary the then newly established Communist Party of Pakistan (CPP), took a radical approach in regards to keeping religion away from class politics, Maulana Bhashani, on the other hand reconciled the friction that existed between religion and Marxism. This was of immense importance for the proper propagation of Marxist politics, for if any progressive movement was to gain momentum within Pakistan, it could never do so while militantly opposing religion, religion had to be given its place within the politics too.

The difference between the opportunistic use of religion in politics and Bhashani’s integration of the spiritual into the political discourse was that his teachings built class consciousness and political awareness.

A unique approach

Maulana Bhashani, as his name suggests, was a religious mentor along with being a political leader. He followed the Sufi tradition of ba’it, where a person submits themselves fully to a spiritual mentor known as a ‘Pir’ in order to successfully travel their spiritual path. The followers of the Pirs who take ba’it on them are called their murids. In the Sufi tradition the pir is deeply revered and respected. This usually makes the murids very loyal to the cause. The thing which was unique about Bhashani was that while giving spiritual guidance to his murids, he also taught them Marxism, thus infusing political and spiritual teachings into a very powerful influx of radical thought and practice.

This approach worked because not only has Sufism always been very popular in the areas of East and West Pakistan, but also because Sufism, like Marxism, takes a very practical and full approach towards reaching its end goal. Thus the idea of practicality was made vital to the murids of Maulana Bhashani. This helped him mobilise a great number from among the masses, numerous times.

The mobilisations during the anti-Ayub movement

It was November of 1968: the whole of Pakistan was engulfed in a fire of inflation, worsening living conditions and a mass uprising that was slowly gaining momentum. The streets echoed of anti-Ayub chants in the months that followed, the air was coloured with hues of anger and frustration directed at the government. In December a large number of peasants, workers and students were mobilized, as a reaction to the declining living conditions. They were observing a Peasants’ Demands Day. The person standing at the helm of the movement, giving the call for observing the day, was Maulana Bhashani. Not a city of East Pakistan could escape the fire that raged in the hearts of the masses when the Maulana gave the call. People were demonstrating angry protests everywhere. Students, workers, peasants, pickpockets, slum-dwellers, beggars, the city poor, all section of the oppressed were active subjects of the movement. This was one of the most powerful scenes from the anti-Ayub movement.

The next year the Maulana again issued a call for a protest, which led to more mass protests. It was during a protest being held against the government’s accusation on Mujib-ur-Rahman, that a sergeant by the name of Zaharul Haq, was shot dead. Next day, on Haq’s funeral, Bhashani called a meeting, and as his voice roared through the crowd, his words “Bengalis awake! And light the fires!” struck the heats of the people. Soon smoke was seen from the city, it was the building of the new headquarters of the Ayub Muslim League that was on fire. It was a coincidence, but it nonetheless made the people enrage with more anger against the State. As they put many government buildings on fire in the days that followed.

Conclusion

The lessons given by Maulana Bhashani teach us something of vital importance. If a revolutionary movement is to be successful, it must take into consideration the beliefs of the people and use them as a catalyst instead of seeing them as an obstacle towards a victory of the people.

Of course, there are many other factors to take into consideration as to why the anti-Ayub movement didn’t lead to a proper revolutionary overthrow of the ruling classes. But the minor victory of Ayub’s overthrow, nonetheless, sheds light on many factors, both beneficial and detrimental to such movements. And Maulana Bhashani’s lessons which must be taken seriously by any progressive today, looking to truly change the oppressive class structures of the society.

Abdul Hamid Khan Bhashani, popularly known as Maulana Bhashani was born in December 1880 in Dhangra village in Sirajganj, Bengal Presidency. His father was named Shafqat Ali Khan. He passed away in Dhaka at the age of 95 on the 17th of November, 1976.

Bhashani was a progressive whose life-long struggle centered on the betterment of the peasants, the workers and the people. Bhashani was very popular amongst the masses, for his unique approach towards progressive politics. While many communist leaders such as Sajjad Zaheer, the General Secretary the then newly established Communist Party of Pakistan (CPP), took a radical approach in regards to keeping religion away from class politics, Maulana Bhashani, on the other hand reconciled the friction that existed between religion and Marxism. This was of immense importance for the proper propagation of Marxist politics, for if any progressive movement was to gain momentum within Pakistan, it could never do so while militantly opposing religion, religion had to be given its place within the politics too.

The difference between the opportunistic use of religion in politics and Bhashani’s integration of the spiritual into the political discourse was that his teachings built class consciousness and political awareness.

A unique approach

Maulana Bhashani, as his name suggests, was a religious mentor along with being a political leader. He followed the Sufi tradition of ba’it, where a person submits themselves fully to a spiritual mentor known as a ‘Pir’ in order to successfully travel their spiritual path. The followers of the Pirs who take ba’it on them are called their murids. In the Sufi tradition the pir is deeply revered and respected. This usually makes the murids very loyal to the cause. The thing which was unique about Bhashani was that while giving spiritual guidance to his murids, he also taught them Marxism, thus infusing political and spiritual teachings into a very powerful influx of radical thought and practice.

This approach worked because not only has Sufism always been very popular in the areas of East and West Pakistan, but also because Sufism, like Marxism, takes a very practical and full approach towards reaching its end goal. Thus the idea of practicality was made vital to the murids of Maulana Bhashani. This helped him mobilise a great number from among the masses, numerous times.

The mobilisations during the anti-Ayub movement

It was November of 1968: the whole of Pakistan was engulfed in a fire of inflation, worsening living conditions and a mass uprising that was slowly gaining momentum. The streets echoed of anti-Ayub chants in the months that followed, the air was coloured with hues of anger and frustration directed at the government. In December a large number of peasants, workers and students were mobilized, as a reaction to the declining living conditions. They were observing a Peasants’ Demands Day. The person standing at the helm of the movement, giving the call for observing the day, was Maulana Bhashani. Not a city of East Pakistan could escape the fire that raged in the hearts of the masses when the Maulana gave the call. People were demonstrating angry protests everywhere. Students, workers, peasants, pickpockets, slum-dwellers, beggars, the city poor, all section of the oppressed were active subjects of the movement. This was one of the most powerful scenes from the anti-Ayub movement.

The next year the Maulana again issued a call for a protest, which led to more mass protests. It was during a protest being held against the government’s accusation on Mujib-ur-Rahman, that a sergeant by the name of Zaharul Haq, was shot dead. Next day, on Haq’s funeral, Bhashani called a meeting, and as his voice roared through the crowd, his words “Bengalis awake! And light the fires!” struck the heats of the people. Soon smoke was seen from the city, it was the building of the new headquarters of the Ayub Muslim League that was on fire. It was a coincidence, but it nonetheless made the people enrage with more anger against the State. As they put many government buildings on fire in the days that followed.

Conclusion

The lessons given by Maulana Bhashani teach us something of vital importance. If a revolutionary movement is to be successful, it must take into consideration the beliefs of the people and use them as a catalyst instead of seeing them as an obstacle towards a victory of the people.

Of course, there are many other factors to take into consideration as to why the anti-Ayub movement didn’t lead to a proper revolutionary overthrow of the ruling classes. But the minor victory of Ayub’s overthrow, nonetheless, sheds light on many factors, both beneficial and detrimental to such movements. And Maulana Bhashani’s lessons which must be taken seriously by any progressive today, looking to truly change the oppressive class structures of the society.