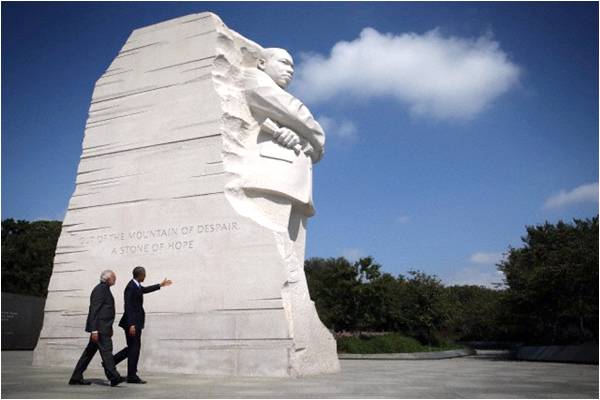

High expectations surrounded the meeting between President Barack Obama and Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi. Washington has pinned its hopes on a strategic partnership with New Delhi and the prospect of large contracts for US corporations, on several previous occasions. But the India-US relationship has moved forward by inches, not miles. Will things be different this time?

Premier Modi’s election campaign generated expectations of a rising or emergent India. Washington DC, like Tokyo and London, is banking on an immediate change not just in style but strategic decision making by New Delhi on foreign and economic policy issues. For decades scholars have referred to India as an ‘emerging power’ or ‘rising power.’ From Washington’s perspective India has not yet risen or emerged.

For two centuries the British viewed colonial India as crucial to maintenance of the British Empire and vital to the security of the Middle East. Both the Soviets and Americans, during the cold war, were keen to have India in their bloc as its size, geographical location and potential resources made India a significant player.

[quote]From Washington’s perspective, India has not yet risen or emerged[/quote]

It was not as though Indians did not understand this fact. Indian leaders and the lay public have always believed that India was a great civilization and a future great power. As India’s first and long serving Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru asserted, India “because of the force of circumstances, because of geography, because of history and because of so many other things, inevitably has to play a very important part in Asia.”

India has been an active member of the United Nations, one of the founding members of the Non Aligned movement, active in all multilateral organizations from World Trade Organization to the World Bank, one of the top contributors to the United Nations peacekeeping forces, and is one of the founders of the nonaligned movement and of the recently formed BRICS (Brazil Russia, India, China and South Africa) grouping. However, to most observers what appears is that India is lacking either the will or the potential to take that extra leap which takes it to the big league.

Nehru framed India’s foreign policy and preferred to keep India away from military and other entanglements. One of the reasons Nehru chose this path was that he knew that foreign policy was dependent on “economic policy” and realized until and unless India was strong economically her “foreign policy will be rather vague, rather inchoate and will be groping.” Instead of being a tactic over time nonalignment became a mantra to be idolized. Nehru’s successors never really properly grasped the importance of economic policy to foreign and security policy.

Under Nehru India played the role of the non-hegemonic big brother amongst the newly emerging decolonized nations. Unfortunately, this status was not commensurate with India’s weak economic potential.

Through the 1950s-80s tremendous time and money was put into economic planning, however, India’s economic growth stayed at a low rate of around 3%, often referred to cynically as the ‘Hindu rate of growth’ by Indian economist Raj Krishna. According to many analysts, part of the blame could be laid at the door of Fabian socialism and the belief that the state should be the engine of both economic growth as well as redistribution.

While economic autarky was championed policies to encourage economic growth were not easily adopted. A certain disdain and suspicion of the private sector was in built from the beginning and stays till this day.

The world changed in terms of both geopolitics and geo-economics with the end of the Cold War, the collapse of the Soviet Union and the spread of globalization. India had to adapt itself to that change. On some levels India initiated immediate change but on others it preferred to wait it out.

Changes were forced upon India on the economic front. Reforms started in the mid-1980s and culminating in 1991 initiated the process of liberalization and the end of the so-called License-Quota Raj. The next two decades saw India benefit from the fruits of these reforms with economic growth going up to almost 10%.

However, a paternalistic state which believed at its core that the market could not to be trusted found it difficult to be at complete ease with economic reforms. The result was, over a period of time, a re-emergence of the state and a slowdown in economic growth.

Many supporters, both domestic and foreign, were disenchanted. Americans, in particular, were disappointed with old ideas still blocking progress on issues such as Intellectual Property Rights, trade and Foreign Direct Investment.

While India re-built ties with the United States on the foreign and security front while India re-built ties yet the old desire to remain independent – non-aligned – manifested itself in the new concept of “strategic autonomy.” There was still an Indian reluctance to deepen ties with the United States.

As any other country in the world and as one which has the capability to be a leading power, India has the right to define or redefine its national interests as it chooses. However, India’s leaders must bear in mind that only deep economic and strategic ties between countries will lead to the country having friends who support it during times of crisis. New Delhi should never forget that during the Sino-Indian conflict of 1962, it was countries like the UK and US who supported India militarily while the nonaligned world remained ‘nonaligned’ between India and China!

Instead of banking solely on ties of history and culture, India needs to build deeper economic and strategic ties both in its region and beyond in Asia. India started the ‘Look East’ policy during the mid-1990s: a policy of building closer ties with the South East and East Asian countries. While closer economic ties have been built, Mumbai, Chennai, Bengaluru and Delhi need to not just ‘look east’ but also ‘involve’ and ‘act’ in the East and invest more deeply in strategic and economic relationships.

When questioned about India’s status in the world Indians often wrongly quote their first Prime Minister Nehru to state: “India need only wait until others understand and accommodate to the Indian position." What they ignore is that complacency has never ensured status; a country has to work for that position and then work to keep that position.

India is today the largest democracy, demographically the second largest country, among the top five global economies and has the third largest army in the world. India’s foreign policy should reflect this and it will only do so when India’s leaders ensure a synchronicity between its economic and foreign policies.

Premier Modi’s election campaign generated expectations of a rising or emergent India. Washington DC, like Tokyo and London, is banking on an immediate change not just in style but strategic decision making by New Delhi on foreign and economic policy issues. For decades scholars have referred to India as an ‘emerging power’ or ‘rising power.’ From Washington’s perspective India has not yet risen or emerged.

For two centuries the British viewed colonial India as crucial to maintenance of the British Empire and vital to the security of the Middle East. Both the Soviets and Americans, during the cold war, were keen to have India in their bloc as its size, geographical location and potential resources made India a significant player.

[quote]From Washington’s perspective, India has not yet risen or emerged[/quote]

It was not as though Indians did not understand this fact. Indian leaders and the lay public have always believed that India was a great civilization and a future great power. As India’s first and long serving Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru asserted, India “because of the force of circumstances, because of geography, because of history and because of so many other things, inevitably has to play a very important part in Asia.”

India has been an active member of the United Nations, one of the founding members of the Non Aligned movement, active in all multilateral organizations from World Trade Organization to the World Bank, one of the top contributors to the United Nations peacekeeping forces, and is one of the founders of the nonaligned movement and of the recently formed BRICS (Brazil Russia, India, China and South Africa) grouping. However, to most observers what appears is that India is lacking either the will or the potential to take that extra leap which takes it to the big league.

Nehru framed India’s foreign policy and preferred to keep India away from military and other entanglements. One of the reasons Nehru chose this path was that he knew that foreign policy was dependent on “economic policy” and realized until and unless India was strong economically her “foreign policy will be rather vague, rather inchoate and will be groping.” Instead of being a tactic over time nonalignment became a mantra to be idolized. Nehru’s successors never really properly grasped the importance of economic policy to foreign and security policy.

Under Nehru India played the role of the non-hegemonic big brother amongst the newly emerging decolonized nations. Unfortunately, this status was not commensurate with India’s weak economic potential.

Through the 1950s-80s tremendous time and money was put into economic planning, however, India’s economic growth stayed at a low rate of around 3%, often referred to cynically as the ‘Hindu rate of growth’ by Indian economist Raj Krishna. According to many analysts, part of the blame could be laid at the door of Fabian socialism and the belief that the state should be the engine of both economic growth as well as redistribution.

While economic autarky was championed policies to encourage economic growth were not easily adopted. A certain disdain and suspicion of the private sector was in built from the beginning and stays till this day.

The world changed in terms of both geopolitics and geo-economics with the end of the Cold War, the collapse of the Soviet Union and the spread of globalization. India had to adapt itself to that change. On some levels India initiated immediate change but on others it preferred to wait it out.

Changes were forced upon India on the economic front. Reforms started in the mid-1980s and culminating in 1991 initiated the process of liberalization and the end of the so-called License-Quota Raj. The next two decades saw India benefit from the fruits of these reforms with economic growth going up to almost 10%.

However, a paternalistic state which believed at its core that the market could not to be trusted found it difficult to be at complete ease with economic reforms. The result was, over a period of time, a re-emergence of the state and a slowdown in economic growth.

Many supporters, both domestic and foreign, were disenchanted. Americans, in particular, were disappointed with old ideas still blocking progress on issues such as Intellectual Property Rights, trade and Foreign Direct Investment.

While India re-built ties with the United States on the foreign and security front while India re-built ties yet the old desire to remain independent – non-aligned – manifested itself in the new concept of “strategic autonomy.” There was still an Indian reluctance to deepen ties with the United States.

As any other country in the world and as one which has the capability to be a leading power, India has the right to define or redefine its national interests as it chooses. However, India’s leaders must bear in mind that only deep economic and strategic ties between countries will lead to the country having friends who support it during times of crisis. New Delhi should never forget that during the Sino-Indian conflict of 1962, it was countries like the UK and US who supported India militarily while the nonaligned world remained ‘nonaligned’ between India and China!

Instead of banking solely on ties of history and culture, India needs to build deeper economic and strategic ties both in its region and beyond in Asia. India started the ‘Look East’ policy during the mid-1990s: a policy of building closer ties with the South East and East Asian countries. While closer economic ties have been built, Mumbai, Chennai, Bengaluru and Delhi need to not just ‘look east’ but also ‘involve’ and ‘act’ in the East and invest more deeply in strategic and economic relationships.

When questioned about India’s status in the world Indians often wrongly quote their first Prime Minister Nehru to state: “India need only wait until others understand and accommodate to the Indian position." What they ignore is that complacency has never ensured status; a country has to work for that position and then work to keep that position.

India is today the largest democracy, demographically the second largest country, among the top five global economies and has the third largest army in the world. India’s foreign policy should reflect this and it will only do so when India’s leaders ensure a synchronicity between its economic and foreign policies.