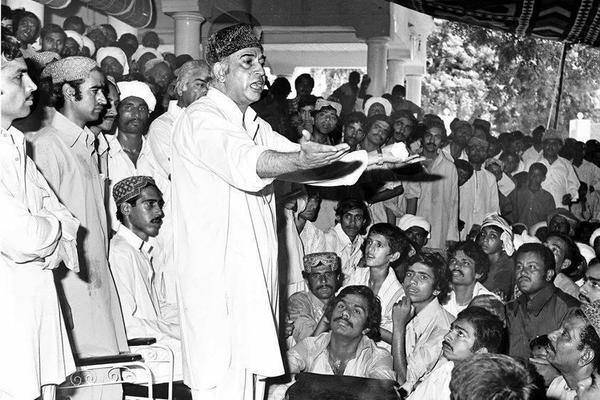

The nation commemorates the 44th death anniversary of the first democratically elected prime minister of Pakistan and the founder of the Pakistan People's Party (PPP), Zulfikar Ali Bhutto. Known for restoring democracy in the country and to a considerable extent for his "political flaws", Bhutto was more of a practical political leader. He is still criticised for some of his decisions of that time.

When it comes to Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, opinion is always mixed. He continues to sharply divide public opinion, decisively along the lines of class, and of support or opposition to civilian supremacy over military hegemony.

The conflicting positions of his admirers and detractors make his character contentious, his ideas divisive, his actions controversial, and his achievements disputed. One may say that the contradictions of Pakistan’s state and society are all manifested in the life and death of Zulfikar Ali Bhutto.

He rose to prominence at an early age, achieved personal and political milestones at an extraordinary pace, and was only 51 when he was hanged to death in 1979. His political career can be divided into four phases. In the first phase (1957-1965), he started his political career by joining president Iskander Mirza’s cabinet. He continued to work under General Ayub Khan after the 1958 military coup. He held various important ministerial portfolios, finally becoming foreign minister in 1963.

It would be wrong to call Bhutto only a political leader: he was an intellectual, with marvelous command over international law and international affairs of his time. Besides that, he was perhaps one of the greatest diplomats Pakistan has ever had. Bhutto was an internationally recognised political leader who left no stone unturned to rebuild Pakistan after the tragedy of the 'Fall of Dhaka'.

It was just because of his intellectual brilliance and political insight that Pakistan crawled back onto the path of development. Bhutto's grasp over international law and international affairs can be gauged from his books 'Myth of Independence' and 'Peacekeeping by UNO'. In those books, he had formulated the ways of ruling a newly formed country, and the actual essence of independence.

As the leader of an underdeveloped country, he was never satisfied with the role of UNO in maintaining peace across the world. In his book, Bhutto had contended that the organisation was formed to appease those forces which anticipated to rule over the world, and the doctrine of veto power at the UN Security Council (UNSC) had proved Bhutto right. Bhutto had significant command over international law, and with that, he delivered brilliantly as a foreign minister. The highlights of this tenure as foreign minister include the initiation of Pakistan’s relationship with China, and success in attracting investment and commerce from countries in the Soviet bloc.

Zulfikar Ali Bhutto’s personal inclination towards the socialist ideology, and his desire to be seen as a pro-people politician, helped him become the chief architect of the Sino-Pakistan strategic relationship that continues to flourish to this day.

His speech at the UN Security Council, after the Indo-Pak war of 1965 over the Kashmir issue, manifested his stance on this decades-old dispute. He vowed to continue the struggle for Kashmir in that speech. After India had launched an attack on Pakistan in 1971, he led the Pakistani delegation to the UN Security Council and apprised the world of Indian aggression. He urged the UNSC and member countries to play their part in ceasefire and reconciliation. But here again, history proved Bhutto right.

As a prime minister, Bhutto would always be remembered for creating awareness about the poor and downtrodden masses. Despite the passage of almost half a century since Zulfikar Ali Bhutto’s time in power (from December 1971 to July 1977), at least five policies and programmes initiated by him not only remain relevant but are considered vital for Pakistan. These initiatives — namely, Pakistan’s nuclear programme; the Constitution of 1973; the Islamic Summit and subsequent export of manpower to Middle East; the development of Pak-China relations; and the Simla Agreement, which ushered in the longest spell of peace in South Asia — can rightfully be considered Bhutto’s true legacy.

Over the years, Bhutto’s idealism has partly faded, but it has not entirely disappeared. In every decade, the spirit and legacy of Bhutto has been revived. His daughter, Benazir Bhutto — the first woman prime minister of the Muslim world — marked the political rebirth of her father’s ideals during the 1980s and 1990s. After she was assassinated in Rawalpindi, her young son Bilawal seized the reins of that legacy, and is struggling to revive and reform his grandfather’s vision amid harsher political realities.

Mr. Bhutto, like other leaders, made mistakes to achieve his political aims and objectives, but he could not secure the opportunity to rectify those mistakes. Unfortunately, the PPP, despite waging a difficult struggle through years of outright and quasi-dictatorship, has yet to build upon that promise of hope enunciated so many years ago.T he current PPP leadership must revisit Bhutto's vision to rekindle his party's fortunes in the national political arena.

When it comes to Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, opinion is always mixed. He continues to sharply divide public opinion, decisively along the lines of class, and of support or opposition to civilian supremacy over military hegemony.

The conflicting positions of his admirers and detractors make his character contentious, his ideas divisive, his actions controversial, and his achievements disputed. One may say that the contradictions of Pakistan’s state and society are all manifested in the life and death of Zulfikar Ali Bhutto.

He rose to prominence at an early age, achieved personal and political milestones at an extraordinary pace, and was only 51 when he was hanged to death in 1979. His political career can be divided into four phases. In the first phase (1957-1965), he started his political career by joining president Iskander Mirza’s cabinet. He continued to work under General Ayub Khan after the 1958 military coup. He held various important ministerial portfolios, finally becoming foreign minister in 1963.

It would be wrong to call Bhutto only a political leader: he was an intellectual, with marvelous command over international law and international affairs of his time. Besides that, he was perhaps one of the greatest diplomats Pakistan has ever had. Bhutto was an internationally recognised political leader who left no stone unturned to rebuild Pakistan after the tragedy of the 'Fall of Dhaka'.

It was just because of his intellectual brilliance and political insight that Pakistan crawled back onto the path of development. Bhutto's grasp over international law and international affairs can be gauged from his books 'Myth of Independence' and 'Peacekeeping by UNO'. In those books, he had formulated the ways of ruling a newly formed country, and the actual essence of independence.

As the leader of an underdeveloped country, he was never satisfied with the role of UNO in maintaining peace across the world. In his book, Bhutto had contended that the organisation was formed to appease those forces which anticipated to rule over the world, and the doctrine of veto power at the UN Security Council (UNSC) had proved Bhutto right. Bhutto had significant command over international law, and with that, he delivered brilliantly as a foreign minister. The highlights of this tenure as foreign minister include the initiation of Pakistan’s relationship with China, and success in attracting investment and commerce from countries in the Soviet bloc.

Zulfikar Ali Bhutto’s personal inclination towards the socialist ideology, and his desire to be seen as a pro-people politician, helped him become the chief architect of the Sino-Pakistan strategic relationship that continues to flourish to this day.

His speech at the UN Security Council, after the Indo-Pak war of 1965 over the Kashmir issue, manifested his stance on this decades-old dispute. He vowed to continue the struggle for Kashmir in that speech. After India had launched an attack on Pakistan in 1971, he led the Pakistani delegation to the UN Security Council and apprised the world of Indian aggression. He urged the UNSC and member countries to play their part in ceasefire and reconciliation. But here again, history proved Bhutto right.

As a prime minister, Bhutto would always be remembered for creating awareness about the poor and downtrodden masses. Despite the passage of almost half a century since Zulfikar Ali Bhutto’s time in power (from December 1971 to July 1977), at least five policies and programmes initiated by him not only remain relevant but are considered vital for Pakistan. These initiatives — namely, Pakistan’s nuclear programme; the Constitution of 1973; the Islamic Summit and subsequent export of manpower to Middle East; the development of Pak-China relations; and the Simla Agreement, which ushered in the longest spell of peace in South Asia — can rightfully be considered Bhutto’s true legacy.

Over the years, Bhutto’s idealism has partly faded, but it has not entirely disappeared. In every decade, the spirit and legacy of Bhutto has been revived. His daughter, Benazir Bhutto — the first woman prime minister of the Muslim world — marked the political rebirth of her father’s ideals during the 1980s and 1990s. After she was assassinated in Rawalpindi, her young son Bilawal seized the reins of that legacy, and is struggling to revive and reform his grandfather’s vision amid harsher political realities.

Mr. Bhutto, like other leaders, made mistakes to achieve his political aims and objectives, but he could not secure the opportunity to rectify those mistakes. Unfortunately, the PPP, despite waging a difficult struggle through years of outright and quasi-dictatorship, has yet to build upon that promise of hope enunciated so many years ago.T he current PPP leadership must revisit Bhutto's vision to rekindle his party's fortunes in the national political arena.