I have a deep-seated regret in my intellectual life—a regret that I believe I will have to carry in the deepest parts of my heart and my mind till the time of my death. I am not familiar with the classical languages of Islam—this is a shortcoming which blocks my understanding Islam, its history, myriad of cultural forms that now encompasses Islamic societies across the world and the praxis that took shape around Islamic philosophies and practices in Muslim societies, over the centuries, in the diverse social, political and cultural forms that now form essential part of multiple Muslim societies in the Middle East, South Asia and Southeast Asia.

My familiarity with these subjects is restricted to my readings in the English language of books written by western authors. In fact, it would not be wrong to conclude that my whole understanding of politics and social realities stems from my readings in the English language. This problem is not exclusively my shortcoming alone. This is rather a shortcoming of my generation.

We have no access to the classical languages of Islam— Arabic and Persian. Urdu to some extent can fill the void in our intellectual life. But much is lost in translation. Besides, in the Urdu language, Islam is presented as an ideology—an over simplified version of a much complex and vast political, social, theological and philosophical set of ideas and philosophies, which, for my generation, have remained buried in the old classical texts, manuscripts and an ocean of literature. In Urdu, Islam is presented simply as a theological and legal religious reality. The literature on Islam in Urdu doesn’t do justice to Islam as a world religion.

We have no access to the classical languages of Islam— Arabic and Persian. Urdu to some extent can fill the void in our intellectual life. But much is lost in translation.

Let me explain: there are presently 49 Muslim countries in the world, which are situated in lands as remote as the Northern tip of Africa to the archipelagos in Southeast Asia. In between, there are umpteen languages, cultural forms and social and political conditions that prevail in Muslim societies. Besides, Islam has embraced a myriad of forms of diverse belief systems and religious and cultural practices in these diverse Muslim societies as a result of a centuries long process of interaction and assimilation with the local cultures in these parts.

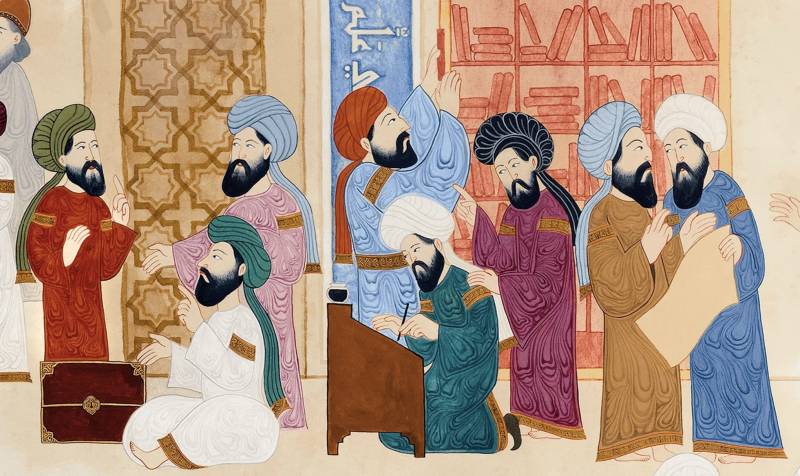

This process of assimilation led to a process of cultural flowering that developed into a myriad of cultural forms, belief systems and artistic and literary and civilizational praxis. The literature in Urdu is just devoid of the depth that can help anyone understand this diversity and depth. And my generation doesn’t have access to literature in Arabic and Persian. There are several western authors who have spent a time studying this diversity and produced a vast literature in the English language. Just like many other members of my generation, I have read a limited number of works and books produced by these authors in the English language.

But there are problems with Western literature on Islam. The Western intellectual tradition on Islam started its life as a colonial project. Western societies like the Dutch, French and English started military expansions in Muslim lands and spread their colonial governance projects in these lands. This necessitated a study of Islamic civilization, its religion, its history, its literature, language and art forms—as a colonial project, it had its own axe to grind, which stemmed from the western cultural, political and civilizational bias. This colonial project was based on Western designs to control Muslim societies.

Intellectual and academic traditions in the western world related to Islam have undergone a sea change since then. There are many western authors who have developed a sympathetic, nuanced view about Islam, its history and its people. But that is not enough. That doesn’t quench the thirst of the people of my generation in Pakistan, who by now have developed a blinkered view of Islam because of two reasons. First, Western scholarship is inherently biased, irrespective of whether the individual author we are talking about is sympathetic towards Islam or not. Often sympathy is not a valuable commodity when it comes to understanding complex cultural concepts. As an example, the study of Hadith literature in British colonial India started as a colonial project and British colonial authors developed the theory that Hadith literature is not historically authentic.

Western societies like the Dutch, French and English started military expansions in Muslim lands and spread their colonial governance projects in these lands. This necessitated a study of Islamic civilization, its religion, its history, its literature, language and art forms—as a colonial project, it had its own axe to grind, which stemmed from the western cultural, political and civilizational bias.

Now you will find a large number of western authors who testify to the authenticity of Hadith literature and discount the western colonial objection that most of the hadith literature was produced more than hundred years after the Prophet’s (PBUH) time. Western authors now take into account the importance of the oral transmission of knowledge in Arabic societies to present hadith literature as authentic. This might be very satisfying for the religious clergy in Pakistani society. But it is hardly the end of the story.

Following this, for one, would mean that we are hostage to an intellectual agenda set for us by the western intellectual tradition. When colonial intellectuals used to challenge hadith literature’s authenticity, we spent our energy on countering their argument. And now when they say it's authentic, we just spent our energy praising these authors. There is no attempt to creatively engage with our past.

In the wake of 9/11, the west, and its media and intellectuals, started to produce literature on Islam, just like their authors produced racy fiction. Edward Said, a Palestinian Christian, challenged the view presented by the western media of Islam. Said was well versed in Arabic because it was his mother tongue and he was a master of western literature. Edward Said's main thesis was that the western media and intellectuals project such a singular dimensional image of Islam, whereas Islam encompasses highly diverse cultural, social and political forms. My generation is primarily dependent on western literature for the understanding of Islam, which borrows the image of Islam as a fundamentalist and legal religion from a literary and intellectual tradition which took birth during the colonial period. Revivalists and fundamentalists traditions in Muslim societies mostly took birth during the British colonial period and this tradition presented Islam as a static, recalcitrant reality which is devoid of any potential for cultural assimilation and evolution.

We are hostage to an intellectual agenda set for us by the western intellectual tradition.

The problem with our generation in Pakistan is that we are presented on the one hand with literature on Islam produced in the English language by western authors, which is biased and reproduces an image of Islam copied from Muslim fundamentalist authors, or literature in Urdu by religious scholars of a more fundamentalist bent, who simply discount the historical and cultural processes through which Islam became a world religion.

For them, the historical processes and cultural assimilation which took place at the grassroots level in Muslim societies does not matter for understanding Islam. Islam, for them, is simply a set of religious and theological principles which link present day societies with the first 30 years of Islam. The rest of the history and cultural dynamism can be discounted in its entirety.

I hope readers will understand the regret that I mentioned at the start of this article. My inability to understand Arabic and Persian will always keep me hostage to western and local fundamentalist literature on Islam. I will never be able to see beyond this limitation. I can only hope that more intellectuals like Edward Said will continue to illuminate our vision.