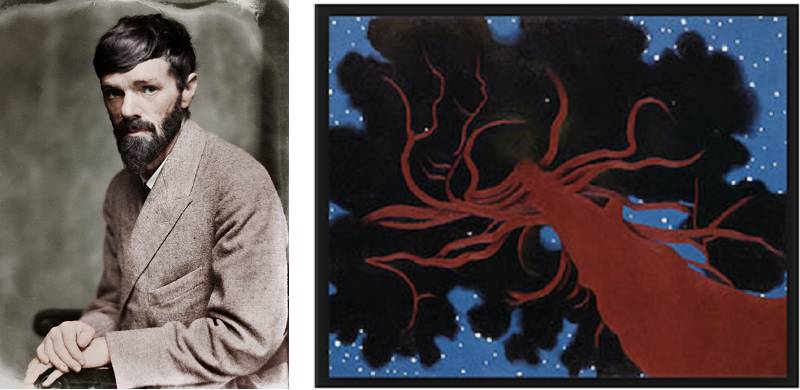

Although D. H. Lawrence (1885-1930) lived in the period commonly designated as modernist, he is not usually considered a typical modernist writer; rather he has been called the last great Romantic by many critics.

Following their dictum to “make it new,” modernist writers introduced technical innovations and experimented with new forms in their works. Well known critic Michael Bell sees the modernist generation as being especially preoccupied with time, personal identity, artistic impersonality, gender, history and myth—concerns also shared by Lawrence, but in a different way. From a historical perspective, literary criticism emerged as an academic specialty for the first time in the modern age. Perhaps this is one of the reasons why more “academic” modernists like Eliot, Joyce and Pound garnered more legitimacy for their artistic practices than did Lawrence. According to Bell, “It is clear[…]that Lawrence does not answer to the view of modernism which, even as the conceptions promoted by Eliot and Pound have been increasingly questioned, still largely governs the perception of it…[Lawrence’s] commitment to the life of feeling made him seem naïve and irrelevant, as well as hostile, to much of this [Eliot, Joyce and Pound’s] programme.”

For Bell, Lawrence stands in a “particularly significant relation” to the other modernists. He seems at first to be marginal to the movement, but he really is central to it, since he provides “one of the most significant critiques of modernism arising from the same historical context and concerns.” Lawrence’s project was parallel to that of the other modernists, both creatively and critically: “He radically disagreed with their understanding of the same important questions concerning art, feeling and the nature of human being.” Lawrence has often been reviled for this difference: he is not cynical enough; not suave enough; he is too intense--to the point of being ridiculous sometimes. (Certainly, he got his share of ridicule, particularly for his “psychology books”—Psychoanalysis and the Unconscious and Fantasia of the Unconscious). And he is hopeful instead of being a purveyor of unmitigated gloom. In the tradition of the great Romantics, he is inspired by nature and the endless renewal and hope it promises.

Lawrence was against art that was totally abstract and divorced from material life. Anne Fernihough notes that: “For Lawrence, things themselves [in their materiality] have been the blind spot of mainstream aesthetic philosophy.” It is this focus on things in themselves that accounts for, in my view, the best writing by Lawrence. Below I discuss briefly two of his nature essays that I find particularly moving and beautiful. Lawrence is justly celebrated for his descriptions of the natural world; they incorporate his preoccupation with showing things in themselves, as objects that exist in the material world with no anthropomorphism to distort them.

“Whistling of Birds” was written in April 1919, just after the war, and contains the theme of unquenchable hope. It is a short essay and therefore perfectly consistent in its form. The essay is an excellent example of F. R. Leavis’s assessment of Lawrence’s perfected art, where “the felt separation between the creatively used words and the piece of living they have the function of evoking is at a minimum. One is not kept conscious of Lawrence—not kept actively aware of him as a personal voice expounding or aiming to evoke.” One does, however, detect a strong, lyrical voice, which is sympathetic and compassionate at the same time. In making its case for hope, it does not turn its eyes away from the destruction of yesterday. The supreme value for Lawrence is life, as many critics have noted, and this essay is an assertion of life. This, incidentally, is also Lawrence’s differentiating characteristic when compared to other modernists. As Donna Miller has observed, Lawrence shared with other modernists “his critical sense of the dislocation of the individual in the face of the modern, industrial world,” but this is where the similarity ended. He “aimed to go beyond mere repudiation and put something in the place of this mechanistic modern order and his attempt was fuelled by Vitalism, a primitivist urge for an elemental, ‘natural’ being, an authentic ethos of life and living.” So it is entirely in keeping with his philosophy when he says:

“We may not choose the world. We have hardly any choice for ourselves. We follow with our eyes the bloody and horrid line of march of extreme winter, as it passes away. But we cannot hold back the spring. We cannot make the birds silent, prevent the bubbling of the wood-pigeons. We cannot stay the fine world of silver-fecund creation from gathering itself and taking place upon us. Whether we will or no, the daphne tree will soon be giving off perfume, the lambs dancing on two feet, the celandines will twinkle all over the ground, there will be a new heaven and new earth.”

The biblical evocations and rhythms of Lawrence’s language are well known. On the one hand they confer a gravity, a solemnity and an authority on this passage. On the other hand, the familiar parallelisms make the reader move in time, as it were, to the language. The positive and negative polarities balance and strengthen each other, and create meaning. The words themselves—“bubbling”; “silver-fecund creation”; “perfume”; “lambs dancing”; “twinkle”—create images that reinforce the assertion of life and hope in the passage, inviting the reader to share in it. The tone and tempo of the writing is sustained to the end, making this, in my opinion, one of the best pieces of nonfiction Lawrence ever wrote.

“Pan in America” was written in New Mexico in 1924. In tone this essay is quite different from “Whistling”; it is also quite uneven in form, Lawrence indulging freely in his philosophy, his likes and dislikes. While some paragraphs are—to my mind--unequalled in beauty of both thought and form, there are others which change the tone so drastically that the essay descends somewhat into bathos. However, the overall quality of the essay does not suffer too much from these passages.

Lawrence starts with invoking the great god Pan of ancient myth in his characteristically effortless way with words:

“But the nymphs, running among the trees and curling to sleep under the bushes, made the myrtles blossom more gaily, and the spring bubble up with greater urge, and the birds splash with a strength of life. And the lithe flanks of the faun gave life to the oak-groves, the vast trees hummed with energy. And the wheat sprouted like green rain returning out of the ground, in the little fields, and the vine hung its black drops in abundance, urging a secret.”

Note the repetition of “and” which has the effect of making the clauses parallel. The comma after “oak-groves” would be a semicolon in traditional grammar, but somehow is more appropriate to the sense of the sentence. It is a very painting, vividly evoking the forest with words like “nymphs,” “trees,” “bushes,” “blossoms,” “spring,” “bubble,” “birds,” “hummed,” “oak-groves,” “wheat,” “green rain!” “vine,” “secret.” Every word reinforces the picture before our eyes. The surprising image of wheat sprouting like green rain out of the ground is original and fresh, and the vine with the black drops is a novel way to describe a grapevine. For Lawrence, Pan is alive in the American continent:

“In the days before man got too much separated off from the universe, he was Pan, along with all the rest.

As a tree still is. A strong-willed, powerful thing-in-itself, reaching up and reaching down. With a powerful will of its own it thrusts green hands and huge limbs at the light above, and sends huge legs and gripping toes down, down between the earth and rocks, to the earth’s middle.”

He then describes the burnt pine tree outside his cabin as the abode of Pan. The tree, which survives to this day, was immortalized by Gorgia O’Keeffe in her 1929 painting The Lawrence Tree. In Lawrence’s strangely haunting description, the tree becomes a living symbol of life and energy: “woody, enormous, slow but unyielding with life, bristling with acquisitive energy, obscurely radiating some of its great strength.” He feels that the tree penetrates his life:

“I am conscious that it helps to change me, vitally. I am even conscious that shivers of energy cross my living plasm, from the tree, and I become a degree more like unto the tree, more bristling and turpentiney, in Pan. And the tree gets a certain shade and alertness of myself, within itself.

Of course, if I like to cut myself off, and say it is all bunk, a tree is merely so much lumber not yet sawn, then in a great measure I shall be cut off. So much depends on one's attitude. One can shut many, many doors of receptivity in oneself; or one can open many doors that are shut.

I prefer to open my doors to the coming of the tree.”

Here is a reiteration of Lawrence’s credo: life consists of a living relation between a human being and the universe surrounding him or her. Lawrence’s preoccupation and engagement with nature has been commented upon by many critics, most recently in a book entitled D. H. Lawrence, Ecofeminism and Nature by Terry Gifford (2023).

In his own prescient, rebellious way, Lawrence continues to be relevant to our concerns today. Our world may be more dystopian now than ever before, with authoritarianism, inequality, polarization, and climate change affecting almost everyone on earth, but we cannot stop hoping. A good place to start would be humility, wonder, and awe in the face of nature.

Following their dictum to “make it new,” modernist writers introduced technical innovations and experimented with new forms in their works. Well known critic Michael Bell sees the modernist generation as being especially preoccupied with time, personal identity, artistic impersonality, gender, history and myth—concerns also shared by Lawrence, but in a different way. From a historical perspective, literary criticism emerged as an academic specialty for the first time in the modern age. Perhaps this is one of the reasons why more “academic” modernists like Eliot, Joyce and Pound garnered more legitimacy for their artistic practices than did Lawrence. According to Bell, “It is clear[…]that Lawrence does not answer to the view of modernism which, even as the conceptions promoted by Eliot and Pound have been increasingly questioned, still largely governs the perception of it…[Lawrence’s] commitment to the life of feeling made him seem naïve and irrelevant, as well as hostile, to much of this [Eliot, Joyce and Pound’s] programme.”

For Bell, Lawrence stands in a “particularly significant relation” to the other modernists. He seems at first to be marginal to the movement, but he really is central to it, since he provides “one of the most significant critiques of modernism arising from the same historical context and concerns.” Lawrence’s project was parallel to that of the other modernists, both creatively and critically: “He radically disagreed with their understanding of the same important questions concerning art, feeling and the nature of human being.” Lawrence has often been reviled for this difference: he is not cynical enough; not suave enough; he is too intense--to the point of being ridiculous sometimes. (Certainly, he got his share of ridicule, particularly for his “psychology books”—Psychoanalysis and the Unconscious and Fantasia of the Unconscious). And he is hopeful instead of being a purveyor of unmitigated gloom. In the tradition of the great Romantics, he is inspired by nature and the endless renewal and hope it promises.

Lawrence was against art that was totally abstract and divorced from material life. Anne Fernihough notes that: “For Lawrence, things themselves [in their materiality] have been the blind spot of mainstream aesthetic philosophy.” It is this focus on things in themselves that accounts for, in my view, the best writing by Lawrence. Below I discuss briefly two of his nature essays that I find particularly moving and beautiful. Lawrence is justly celebrated for his descriptions of the natural world; they incorporate his preoccupation with showing things in themselves, as objects that exist in the material world with no anthropomorphism to distort them.

“Whistling of Birds” was written in April 1919, just after the war, and contains the theme of unquenchable hope. It is a short essay and therefore perfectly consistent in its form. The essay is an excellent example of F. R. Leavis’s assessment of Lawrence’s perfected art, where “the felt separation between the creatively used words and the piece of living they have the function of evoking is at a minimum. One is not kept conscious of Lawrence—not kept actively aware of him as a personal voice expounding or aiming to evoke.” One does, however, detect a strong, lyrical voice, which is sympathetic and compassionate at the same time. In making its case for hope, it does not turn its eyes away from the destruction of yesterday. The supreme value for Lawrence is life, as many critics have noted, and this essay is an assertion of life. This, incidentally, is also Lawrence’s differentiating characteristic when compared to other modernists. As Donna Miller has observed, Lawrence shared with other modernists “his critical sense of the dislocation of the individual in the face of the modern, industrial world,” but this is where the similarity ended. He “aimed to go beyond mere repudiation and put something in the place of this mechanistic modern order and his attempt was fuelled by Vitalism, a primitivist urge for an elemental, ‘natural’ being, an authentic ethos of life and living.” So it is entirely in keeping with his philosophy when he says:

“We may not choose the world. We have hardly any choice for ourselves. We follow with our eyes the bloody and horrid line of march of extreme winter, as it passes away. But we cannot hold back the spring. We cannot make the birds silent, prevent the bubbling of the wood-pigeons. We cannot stay the fine world of silver-fecund creation from gathering itself and taking place upon us. Whether we will or no, the daphne tree will soon be giving off perfume, the lambs dancing on two feet, the celandines will twinkle all over the ground, there will be a new heaven and new earth.”

The biblical evocations and rhythms of Lawrence’s language are well known. On the one hand they confer a gravity, a solemnity and an authority on this passage. On the other hand, the familiar parallelisms make the reader move in time, as it were, to the language. The positive and negative polarities balance and strengthen each other, and create meaning. The words themselves—“bubbling”; “silver-fecund creation”; “perfume”; “lambs dancing”; “twinkle”—create images that reinforce the assertion of life and hope in the passage, inviting the reader to share in it. The tone and tempo of the writing is sustained to the end, making this, in my opinion, one of the best pieces of nonfiction Lawrence ever wrote.

“Pan in America” was written in New Mexico in 1924. In tone this essay is quite different from “Whistling”; it is also quite uneven in form, Lawrence indulging freely in his philosophy, his likes and dislikes. While some paragraphs are—to my mind--unequalled in beauty of both thought and form, there are others which change the tone so drastically that the essay descends somewhat into bathos. However, the overall quality of the essay does not suffer too much from these passages.

Lawrence starts with invoking the great god Pan of ancient myth in his characteristically effortless way with words:

“But the nymphs, running among the trees and curling to sleep under the bushes, made the myrtles blossom more gaily, and the spring bubble up with greater urge, and the birds splash with a strength of life. And the lithe flanks of the faun gave life to the oak-groves, the vast trees hummed with energy. And the wheat sprouted like green rain returning out of the ground, in the little fields, and the vine hung its black drops in abundance, urging a secret.”

Note the repetition of “and” which has the effect of making the clauses parallel. The comma after “oak-groves” would be a semicolon in traditional grammar, but somehow is more appropriate to the sense of the sentence. It is a very painting, vividly evoking the forest with words like “nymphs,” “trees,” “bushes,” “blossoms,” “spring,” “bubble,” “birds,” “hummed,” “oak-groves,” “wheat,” “green rain!” “vine,” “secret.” Every word reinforces the picture before our eyes. The surprising image of wheat sprouting like green rain out of the ground is original and fresh, and the vine with the black drops is a novel way to describe a grapevine. For Lawrence, Pan is alive in the American continent:

“In the days before man got too much separated off from the universe, he was Pan, along with all the rest.

As a tree still is. A strong-willed, powerful thing-in-itself, reaching up and reaching down. With a powerful will of its own it thrusts green hands and huge limbs at the light above, and sends huge legs and gripping toes down, down between the earth and rocks, to the earth’s middle.”

He then describes the burnt pine tree outside his cabin as the abode of Pan. The tree, which survives to this day, was immortalized by Gorgia O’Keeffe in her 1929 painting The Lawrence Tree. In Lawrence’s strangely haunting description, the tree becomes a living symbol of life and energy: “woody, enormous, slow but unyielding with life, bristling with acquisitive energy, obscurely radiating some of its great strength.” He feels that the tree penetrates his life:

“I am conscious that it helps to change me, vitally. I am even conscious that shivers of energy cross my living plasm, from the tree, and I become a degree more like unto the tree, more bristling and turpentiney, in Pan. And the tree gets a certain shade and alertness of myself, within itself.

Of course, if I like to cut myself off, and say it is all bunk, a tree is merely so much lumber not yet sawn, then in a great measure I shall be cut off. So much depends on one's attitude. One can shut many, many doors of receptivity in oneself; or one can open many doors that are shut.

I prefer to open my doors to the coming of the tree.”

Here is a reiteration of Lawrence’s credo: life consists of a living relation between a human being and the universe surrounding him or her. Lawrence’s preoccupation and engagement with nature has been commented upon by many critics, most recently in a book entitled D. H. Lawrence, Ecofeminism and Nature by Terry Gifford (2023).

In his own prescient, rebellious way, Lawrence continues to be relevant to our concerns today. Our world may be more dystopian now than ever before, with authoritarianism, inequality, polarization, and climate change affecting almost everyone on earth, but we cannot stop hoping. A good place to start would be humility, wonder, and awe in the face of nature.