It is difficult to recall the year, much less the month. It was probably 1976. I had just entered the field of journalism through the weekly Me’yaar, which represented the views of the People’s Party and was edited by eminent journalist Mehmood Shaam. But ever since my student days I had supported the pro-Moscow faction of the National Awami Party (NAP) led by Khan Abdul Wali Khan and had a strong relationship with its Baloch leadership through the Baloch Student Organisation (BSO). The weekly Me’yaar was close to the PPP but seeing my affinity with NAP, Mehmood Shaam assigned me opposition parties, especially NAP whose leadership was then being prosecuted in Hyderabad jail on charges of treason. I requested the then BSO Secretary Majeed Baloch, a protégé of the great Baloch leader Mir Ghaus Bakhsh Bizenjo, to arrange for my interview with some of the detained Baloch leaders.

So one morning I took the bus to Hyderabad and reached the jail in four hours. There I saw for the first time what a jail looks like from the inside and how a trial is held there. Little did I know at the time that I would be spending a few months in this very jail when Ziaul Haq would declare his martial law. It is also besides the point that back then, we went to jail for the freedom of the press. The weekly Me’yaar and my salary of three hundred rupees were also shut down by the martial law. Today, the spearheads of a large media group claim to be fighting the battle of the century for the freedom of press. Mashallah, this battle is being fought on screen and op-ed pages with salaries of millions of rupees without any fear of censors, jails, or unemployment.

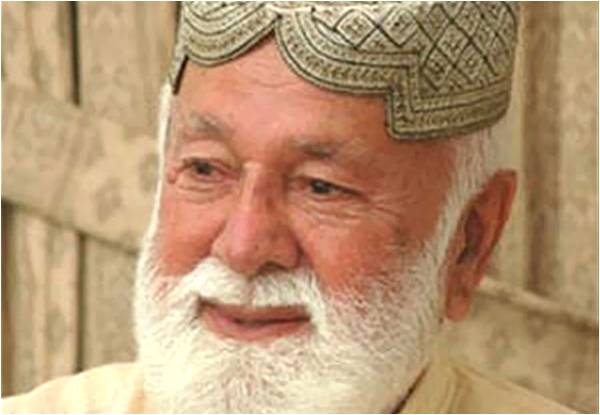

My purpose, however, in referring to the Hyderabad Conspiracy case is to pay tribute to Nawab Khair Bakhsh Marri, who was the most charismatic, mesmerising, stern and prominent of the 66 Baloch and Patkhtoon leaders detained at the Hyderabad Jail.

I passed through four iron doors on my way to the courtroom and found it filled with shouts and cries. The presiding judge, Justice Rehman, seemed hopeless in the face of the sharp and biting questions being raised by Baloch and Pakhtoon detainees. The judges were further pressed when prominent lawyer Mian Mehmood Ali Kasuri roared that it was hardly democratic or just for lawyers and judges to be detained within the four walls of the jail along with other detainees. Kasuri’s remark prompted Jalib – one of the few brave Punjabi intellectuals and politicians who had for years been fighting shoulder to shoulder with the Baloch and the Pakhtoons against the Bhutto government – to cry out from the back of the courtroom:

These judges, prisoners themselves, cannot give us justice

Their decision is written clearly on their faces.

After a lot of hullabaloo, the judicial proceedings were adjourned. I reached the visitor’s room to try to briefly interview some of the detainees. There Majeed Baloch introduced me to Mir Ghaus Bakhsh Bizenjo who handed me a copy of a testimony he had given to the court and asked me to see if our magazine would carry it despite its pro-Bhutto leanings. Our magazine did carry the entire statement and Mir sahib would often mention this episode in the years to come. After greeting Mir sahib, I wanted to see Nawab Khair Bakhsh Marri from up close. I already knew that Nawab sahib seldom spoke. The small visitors’ room was so cramped for air I had to go outside. Standing there, I saw that a tall man, dressed in white khaadi and elegant as a Greek prince, was briskly walking along the prison walls. Jalib, who was standing next to me, informed me that Nawab sahib walks like this for a couple of hours every day until he is drenched in sweat. He also told me not to approach him as he did not talk to anyone in the jail, not even to his commander Sher Muhammad Marri who was also detained in the same jail. So I left the jail with my desire to meet Nawab sahib unfulfilled.

[quote]The demise of NAP ended a glorious chapter in the history of progressive, secular and nationalist politics in Balochistan and Khyber Pakhtoonkhwa[/quote]

When General Zia imposed his martial law in July 1977, he closed down the Hyderabad Conspiracy case and released the Baloch and Pakthoon leaders. However, after their release, the Baloch leaders not only drifted away from the Pakhtoon leaders but also from each other. The demise of NAP and differences between the Baloch and Pakhtoon leaders ended a glorious chapter in the history of progressive, secular and nationalist politics in Balochistan and Khyber Pakhtoonkhwa. BM Kutty, a prominent progressive intellectual from Kerala, has tried to sum up in a book this long history from the 60s to the 80s but his focus has been Mir Ghaus Bakhsh Bizenjo, whom he served as his political secretary for a while. I have written a brief book titled What is the Baloch problem? but this is a heavy burden. I will try to write a detailed account if I get a break from the screen, which is my bread and butter.

I reached Quetta a day after the release of Baloch leaders. I was the first journalist to interview Bizenjo after his release. When the magazine arrived at Mansoor Bukhari’s sales and service centre in Quetta, with Bizenjo’s picture on the cover, it sold eight thousand copies in one evening. After this, I naturally wished to meet Nawab Khair Bakhsh Marri and Sher Muhammad Marri. I should perhaps note here that there were four big names in the Baloch politics of the 70s: Bizenjo, Sardar Attaullah Mengal, Nawab Khair Bakhsh Marri and Akbar Khan Bugti.

Mengal had gone to London for medical treatment. Bugti had developed differences with the NAP leadership. Every BSO or NAP leader I asked in Quetta to introduce me to Nawab Marri refused with an apology. One evening my dear friend Shaheed Raziq Bugti proposed we go see “Sheru Baba” at his place and try to get an interview with them. About a furlong down Saryab Road, more than a hundred armed Marris were sitting in circle in a vast courtyard wearing their stern looks and dense beards along with their distinctive style of shalwar-kameez. Sher Muhammad Marri, whom Bhutto had nicknamed General Sherof, was sitting in the middle. Sitting beside Sher Muhammad Marri, with his head lowered, was Nawab Khair Bakhsh Marri. It was February and became colder after sunset. After exchanging traditional Baloch greetings, Sher Muhammad Marri agreed to give us an interview that very night. However, Nawab sahib did not even look up and only mumbled a little in response to my request for an interview. Sher Muhammad Marri’s interview, printed in the weekly Me’yaar with a full-colour photo of his fair face and dense beard on the cover, also made record sales in Balochistan. However, I returned from Quetta while still wishing to interview Nawab Khair Bakhsh Marri.

When I heard the news of his death last Thursday, it felt as if an entire chapter of the Baloch resistance movement had been left unwritten. Nawab Khair Bakhsh Marri was 86 years old. His father passed away when he was three. He went to Aitchison College in Lahore. During Ayub Khan’s rule, he was in the assembly for some time but was later sent to jail. When the first general elections on the basis of adult suffrage were held in 1970 and, after a long while, the elected Baloch leadership got an opportunity to form a government of their own, it was hoped that the Bizenjo-Mengal-Marri troika would bring a ray of hope to the lives of poor and illiterate Baloch. However, the betrayal of friends and cruelty of foes sent this government packing in just nine months. After his release from the Hyderabad Conspiracy case, Nawab Khair Bakhsh spent a long time in exile. He eventually returned to live a quiet life in Pakistan. Nawab Khair Bakhsh Marri was a prince of Baloch politics whose efforts and sacrifices will adorn the pages of history.

So one morning I took the bus to Hyderabad and reached the jail in four hours. There I saw for the first time what a jail looks like from the inside and how a trial is held there. Little did I know at the time that I would be spending a few months in this very jail when Ziaul Haq would declare his martial law. It is also besides the point that back then, we went to jail for the freedom of the press. The weekly Me’yaar and my salary of three hundred rupees were also shut down by the martial law. Today, the spearheads of a large media group claim to be fighting the battle of the century for the freedom of press. Mashallah, this battle is being fought on screen and op-ed pages with salaries of millions of rupees without any fear of censors, jails, or unemployment.

My purpose, however, in referring to the Hyderabad Conspiracy case is to pay tribute to Nawab Khair Bakhsh Marri, who was the most charismatic, mesmerising, stern and prominent of the 66 Baloch and Patkhtoon leaders detained at the Hyderabad Jail.

I passed through four iron doors on my way to the courtroom and found it filled with shouts and cries. The presiding judge, Justice Rehman, seemed hopeless in the face of the sharp and biting questions being raised by Baloch and Pakhtoon detainees. The judges were further pressed when prominent lawyer Mian Mehmood Ali Kasuri roared that it was hardly democratic or just for lawyers and judges to be detained within the four walls of the jail along with other detainees. Kasuri’s remark prompted Jalib – one of the few brave Punjabi intellectuals and politicians who had for years been fighting shoulder to shoulder with the Baloch and the Pakhtoons against the Bhutto government – to cry out from the back of the courtroom:

These judges, prisoners themselves, cannot give us justice

Their decision is written clearly on their faces.

After a lot of hullabaloo, the judicial proceedings were adjourned. I reached the visitor’s room to try to briefly interview some of the detainees. There Majeed Baloch introduced me to Mir Ghaus Bakhsh Bizenjo who handed me a copy of a testimony he had given to the court and asked me to see if our magazine would carry it despite its pro-Bhutto leanings. Our magazine did carry the entire statement and Mir sahib would often mention this episode in the years to come. After greeting Mir sahib, I wanted to see Nawab Khair Bakhsh Marri from up close. I already knew that Nawab sahib seldom spoke. The small visitors’ room was so cramped for air I had to go outside. Standing there, I saw that a tall man, dressed in white khaadi and elegant as a Greek prince, was briskly walking along the prison walls. Jalib, who was standing next to me, informed me that Nawab sahib walks like this for a couple of hours every day until he is drenched in sweat. He also told me not to approach him as he did not talk to anyone in the jail, not even to his commander Sher Muhammad Marri who was also detained in the same jail. So I left the jail with my desire to meet Nawab sahib unfulfilled.

[quote]The demise of NAP ended a glorious chapter in the history of progressive, secular and nationalist politics in Balochistan and Khyber Pakhtoonkhwa[/quote]

When General Zia imposed his martial law in July 1977, he closed down the Hyderabad Conspiracy case and released the Baloch and Pakthoon leaders. However, after their release, the Baloch leaders not only drifted away from the Pakhtoon leaders but also from each other. The demise of NAP and differences between the Baloch and Pakhtoon leaders ended a glorious chapter in the history of progressive, secular and nationalist politics in Balochistan and Khyber Pakhtoonkhwa. BM Kutty, a prominent progressive intellectual from Kerala, has tried to sum up in a book this long history from the 60s to the 80s but his focus has been Mir Ghaus Bakhsh Bizenjo, whom he served as his political secretary for a while. I have written a brief book titled What is the Baloch problem? but this is a heavy burden. I will try to write a detailed account if I get a break from the screen, which is my bread and butter.

I reached Quetta a day after the release of Baloch leaders. I was the first journalist to interview Bizenjo after his release. When the magazine arrived at Mansoor Bukhari’s sales and service centre in Quetta, with Bizenjo’s picture on the cover, it sold eight thousand copies in one evening. After this, I naturally wished to meet Nawab Khair Bakhsh Marri and Sher Muhammad Marri. I should perhaps note here that there were four big names in the Baloch politics of the 70s: Bizenjo, Sardar Attaullah Mengal, Nawab Khair Bakhsh Marri and Akbar Khan Bugti.

Mengal had gone to London for medical treatment. Bugti had developed differences with the NAP leadership. Every BSO or NAP leader I asked in Quetta to introduce me to Nawab Marri refused with an apology. One evening my dear friend Shaheed Raziq Bugti proposed we go see “Sheru Baba” at his place and try to get an interview with them. About a furlong down Saryab Road, more than a hundred armed Marris were sitting in circle in a vast courtyard wearing their stern looks and dense beards along with their distinctive style of shalwar-kameez. Sher Muhammad Marri, whom Bhutto had nicknamed General Sherof, was sitting in the middle. Sitting beside Sher Muhammad Marri, with his head lowered, was Nawab Khair Bakhsh Marri. It was February and became colder after sunset. After exchanging traditional Baloch greetings, Sher Muhammad Marri agreed to give us an interview that very night. However, Nawab sahib did not even look up and only mumbled a little in response to my request for an interview. Sher Muhammad Marri’s interview, printed in the weekly Me’yaar with a full-colour photo of his fair face and dense beard on the cover, also made record sales in Balochistan. However, I returned from Quetta while still wishing to interview Nawab Khair Bakhsh Marri.

When I heard the news of his death last Thursday, it felt as if an entire chapter of the Baloch resistance movement had been left unwritten. Nawab Khair Bakhsh Marri was 86 years old. His father passed away when he was three. He went to Aitchison College in Lahore. During Ayub Khan’s rule, he was in the assembly for some time but was later sent to jail. When the first general elections on the basis of adult suffrage were held in 1970 and, after a long while, the elected Baloch leadership got an opportunity to form a government of their own, it was hoped that the Bizenjo-Mengal-Marri troika would bring a ray of hope to the lives of poor and illiterate Baloch. However, the betrayal of friends and cruelty of foes sent this government packing in just nine months. After his release from the Hyderabad Conspiracy case, Nawab Khair Bakhsh spent a long time in exile. He eventually returned to live a quiet life in Pakistan. Nawab Khair Bakhsh Marri was a prince of Baloch politics whose efforts and sacrifices will adorn the pages of history.