Random House India, 2014)

This is probably one of the most opportune times to release a book on the troubled present and thorny past of the Pashtuns defined by centuries of empire building, resistance to great powers and endemic violence.

In recent years the Pashtun regions have been defined by the complicated counterinsurgency campaigns more than 300,000 NATO and Pakistani troops have been waging in Afghanistan and Pakistan. With the imminent withdrawal of most Western combat troops from Afghanistan by the end of this year, the Pakistani army is in the midst of what it calls a “comprehensive operation” in North Waziristan.

These complicated struggles require a new understanding of what afflicts the Pashtun homeland in Afghanistan and Pakistan. Abubakar Siddique, a journalist from Waziristan, has done this in his deeply researched and riveting book, The Pashtuns: The Unresolved Key to the Future of Pakistan and Afghanistan.

Siddique has done away with many stereotypes associated with the Pashtuns by writing a precise and comprehensive history of their society and homeland in the first couple of chapters. The Pashtuns presents a gripping account of the last five centuries of Pashtun history from the rise of the moderate Roshnya movement in the 16th century to the demise of Afghanistan’s Taliban regime in 2001. He has shown that today’s ideological struggles and scramble for power in the Pashtun homeland either reflect those of the past centuries or are their continuation.

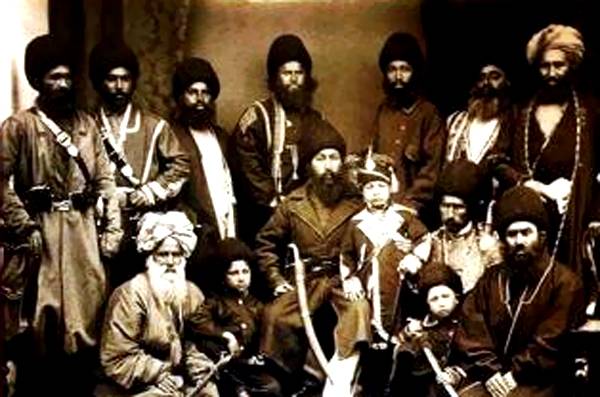

[quote]Wahabis were initially welcomed by some Pashtuns because they were seen as defenders of Muslims against tyrant

Sikh rulers[/quote]

Interestingly, many of these ideologies were alien to the land and directly clashed with the cultural and social ethos of the Pashtuns. A good example of this was the 19th Century jihad movement of Sayyid Ahmed from Ray Barelli in India, formally known as the Tariqi-ye Muhammadiyya or the Wahhabi movement. This faction was initially welcomed by some Pashtuns in Peshawar valley because they were seen as defenders of Muslims against tyrant Sikh rulers. But the followers of Sayyid Ahmed were soon despised because of their insistence on the enforcement of harsh rules and oppression of locals in the name of implementing Islam. This eventually led to a Pashtun rebellion and Ahmed’s followers were expelled from Peshawar in 1831.

The 19th century Great Game saw Pashtun lands turn into a buffer between British India and Tzarist Russia. And in 1973 when the Durrani dynasty was converted into a republic, Afghanistan became the battleground for alien ideologies, including, communism, capitalism and various shades of Islamism. The Pashtun regions have been in turmoil since then and its residents have suffered as a result. The Pashtun and other Afghan ethnic groups paid with their blood to change the Cold War into a hot war. Their struggle ultimately contributed to the demise of the Soviet Union and the socialist bloc it led.

Siddique then sets out the scene for the analysis of the ten years of war, death and destruction in the Pashtun belt in Pakistan. The chapter on Waziristan provides the perspective of an insider. The author first saw refugees coming in droves from Afghanistan after the Soviet occupation of the early 1980s and after the emergence of the Taliban two decades later. Contrary to popular perceptions and claims of some leading Pakistani politicians, the Pakistani Taliban is not a post 9/11 phenomenon in Waziristan. Even before the 9/11 attacks in the United States, a certain Mullah Manan had told the author: “We have taken care of Ahmad Shah Massoud, and we will soon come to Pakistan to implement true Islam here.”

A year or so later the first clash between the militants and security forces took place in South Waziristan. This violence gradually turned into a robust terror campaign and insurgency in which thousands of soldiers, ordinary people and tribal leaders were killed. A number of foreigners also came to the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA) to establish sanctuaries. According to some observers, the state apparatus made no real effort to stop these people. This resulted in all of FATA and the settled districts of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa being gradually engulfed by this fire. Siddique has explored the instability in Swat in detail where a mix of social, political and economic factors combined to create a lethal combination of local Taliban under the leadership of Mullah Fazlullah alias Mullah Radio, the current head of Tehreek-e Taliban Pakistan.

The third part explores the Pashtun areas of Afghanistan which the author has divided into three regions: Loy Nangarhar, Loya Paktia and Loy Qandahar (Loy being the Pashto word for greater). Although the Loy Nangarhar and Loy Qandahar are important for their histories of Islamist rebellion and movements, it is the Loya Paktia chapter that makes an interesting and extremely valuable read. Currently home to one of the most lethal and dangerous insurgent group, the Haqqani Network, which has ties to both the Quetta Shura (or Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan under the leadership of Mullah Muhammad Omer) and al Qaeda, Loya Paktia had once been a center of gravity for Afghanistan’s communists. This area, home to some large Pashtun tribes, has historically provided surrogate armies to the Afghan state.

But in the 1950s and early 1960s, when the professional Afghan army was organized, many of the youth of this area joined the military academy of Kabul. Many of them were then sent for training to USSR. Upon returning from there they sought to change the Afghan society through a socialist revolution. But the dream went sour after the April 1978 coup (called the Saur Revolution by the Afghan communists) when one after another regimes fell and an unending war engulfed the country. As one former communist official told Siddique: such coups can never achieve the aspirations of genuine revolutions; we were indoctrinated by the teachings of an alien ideology, which prompted us to call our military coup a revolution. We then mistakenly established revolutionary goals for the regime formed after a military coup.

It is difficult to disagree with the conclusions of Siddique’s illuminating book. His paradigm that today’s instability is the result of Afghanistani and Pakistani failure to integrate the Pashtuns is a valid one. As an example the draconian colonial-era Frontier Crimes Regulations law is still in place in FATA. Siddique’s proposal of cooperative, friendly relations between Afghanistan and Pakistan, including permanently opening their common border, now seems realistic after generations of proxy wars have failed to secure Islamabad.

Aided by thorough field research in one of the most dangerous theatres of war in the world The Pashtun is a must read for scholars, policymakers and general readers of politics and history.