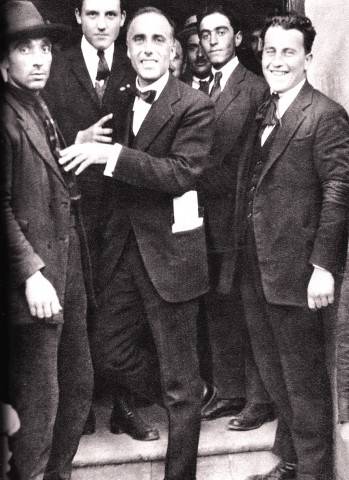

This photograph shows Giacomo Matteotti with his supporters in the early 1920s. Matteotti was an Italian socialist politician. On May 30, 1924, he openly spoke in the Italian parliament alleging the Fascists committed fraud in the recently held elections and denounced the violence they used to gain votes. Eleven days later, he was kidnapped and killed by Fascists.

This assassination by Fascists shocked world opinion and shook Benito Mussolini’s regime. The Matteotti Crisis, as the event came to be known, initially threatened to bring about the downfall of the Fascists but instead ended with Mussolini as the absolute dictator of Italy.

After graduating from the University of Bologna law school, Matteotti entered law practice and joined the Italian Socialist Party. He was elected to the Chamber of Deputies in 1919 and reelected in 1921 and 1924, by which time he had become secretary general of his party. In the meantime, Mussolini, who had succeeded in gaining power, was conducting terroristic attacks on leftists. On May 30, 1924, Matteotti addressed a ringing denunciation of the Fascist Party to the Chamber. Less than two weeks later (June 10) six Fascist squadristi kidnapped Matteotti in Rome, murdered him, and hastily buried his body outside the city near Riano Flaminio.

Matteotti’s disappearance created a sensation, as did the discovery of his body a few weeks later. The Italian public had no doubt that Fascists were implicated in the crime and reacted against Fascist rule. Fascist party badges disappeared overnight; the antechamber of Mussolini’s office, usually full, stood empty.

The opposition deputies withdrew from the Chamber, in an action known as the Aventine secession, to protest the murder and to work for the overthrow of Mussolini. But the parliamentary forces, powerless before in the events leading to Mussolini’s seizure of power in 1922, proved ineffective in keeping public opinion aroused and failed to take decisive action against Mussolini. Despite a prolonged judicial inquiry, the six suspects arrested for the murder were allowed to go free.

Mussolini, at first taken aback by his loss of public favor, decided to take the offensive. On January 3, 1925, in a speech to the Chamber, he took full responsibility for the murder as head of the Fascist party (although whether he gave a direct order for the murder remains uncertain) and dared his critics to prosecute him for the crime, a challenge that never was made since they were too weak to take it up.

The Matteotti Crisis marked a turning point in the history of Italian Fascism. Mussolini abandoned any plan of working with parliament and took steps to create a totalitarian state, including suppression of the opposition press, exclusion of non-Fascist ministers, and formation of a secret police.

This assassination by Fascists shocked world opinion and shook Benito Mussolini’s regime. The Matteotti Crisis, as the event came to be known, initially threatened to bring about the downfall of the Fascists but instead ended with Mussolini as the absolute dictator of Italy.

After graduating from the University of Bologna law school, Matteotti entered law practice and joined the Italian Socialist Party. He was elected to the Chamber of Deputies in 1919 and reelected in 1921 and 1924, by which time he had become secretary general of his party. In the meantime, Mussolini, who had succeeded in gaining power, was conducting terroristic attacks on leftists. On May 30, 1924, Matteotti addressed a ringing denunciation of the Fascist Party to the Chamber. Less than two weeks later (June 10) six Fascist squadristi kidnapped Matteotti in Rome, murdered him, and hastily buried his body outside the city near Riano Flaminio.

Matteotti’s disappearance created a sensation, as did the discovery of his body a few weeks later. The Italian public had no doubt that Fascists were implicated in the crime and reacted against Fascist rule. Fascist party badges disappeared overnight; the antechamber of Mussolini’s office, usually full, stood empty.

The opposition deputies withdrew from the Chamber, in an action known as the Aventine secession, to protest the murder and to work for the overthrow of Mussolini. But the parliamentary forces, powerless before in the events leading to Mussolini’s seizure of power in 1922, proved ineffective in keeping public opinion aroused and failed to take decisive action against Mussolini. Despite a prolonged judicial inquiry, the six suspects arrested for the murder were allowed to go free.

Mussolini, at first taken aback by his loss of public favor, decided to take the offensive. On January 3, 1925, in a speech to the Chamber, he took full responsibility for the murder as head of the Fascist party (although whether he gave a direct order for the murder remains uncertain) and dared his critics to prosecute him for the crime, a challenge that never was made since they were too weak to take it up.

The Matteotti Crisis marked a turning point in the history of Italian Fascism. Mussolini abandoned any plan of working with parliament and took steps to create a totalitarian state, including suppression of the opposition press, exclusion of non-Fascist ministers, and formation of a secret police.