When the white rule ended in South Africa, and the jailed leader Nelson Mandela became the first black president in its post-apartheid history, there were, quite justifiably, anguished cries for punishment and retribution, especially from the black majority who had suffered on account of human rights abuses—often meaning torture and extra-judicial killings of African National Congress (ANC) workers—during the apartheid era. With the passing of specific legislation in this regard, i.e., the Promotion of National Unity and Reconciliation Act 1995, South Africa made a collective effort to heal the deep wounds inflicted during the racist white rule.

At the time, setting up the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) under the above-mentioned law was hailed as one of the most humane ways to bring together two communities that had been at war with each other from time immemorial. One of the main objects of the TRC was to provide for the investigation and establishment of as complete a picture as possible of the nature, causes, and extent of gross violations of human rights committed during the period from March 1, 1960, to the cut-off date which was stipulated to be in 1994.

The Commission conducted its proceedings/hearings for almost three years before a report was compiled and submitted to President Mandela. Although the hearings became known for emotional outpourings of the victims’ families with Archbishop Desmond Tutu’s invocation of religion for healing by singing Christian hymns outside the venues along with his followers, but the most crucial element of the whole process was the conditional amnesty offered to those who gave full disclosure about gross violations of human rights perpetrated for political motives.

Most commentators and jurists agreed on the need for transitional justice for a newly formed democracy like South Africa, watchfully and farsightedly midwifed by one of the greatest leaders of the 20th century, Nelson Mandela. Like South Africa in the early 1990s, Pakistan seems on the cusp of a negotiated transition from its currently controlled democracy to a polity where the will of the people through the parliament is supreme. Although both case studies have different facts and sets of history, the idea of a truth commission for the latter may not just be a pipedream.

Like South Africa, Pakistan’s criminal justice system suffers from a chronic lack of capacity and inability to prosecute those responsible for consistently undermining its political system, hence the need for a locally tailored truth commission

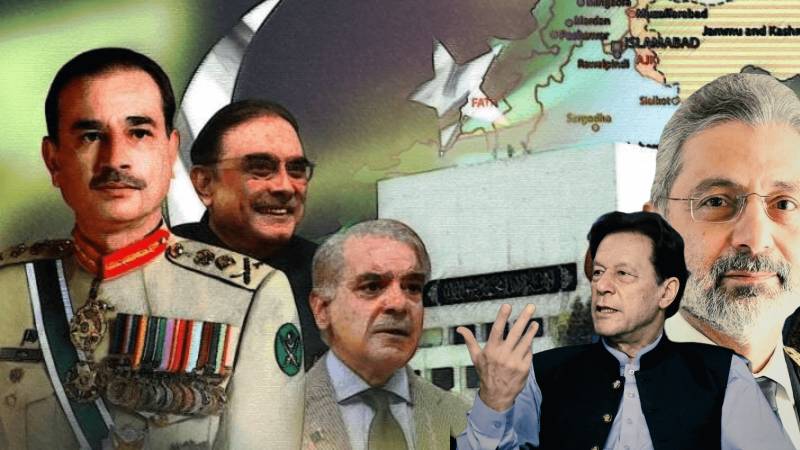

Pakistan’s civil society has grappled and fought with the gratuitous overreach of the military to bring at least a semblance of normalcy to its democracy, but with little success. Political engineering or, in other words, a network of agencies creating desired results, especially in the electoral processes, as well as vis-à-vis political leaders who have gone past their ‘sell by’ dates, have had pushbacks from the civil society whenever a scarce little chance was presented in history. The Supreme Court, politicians and the media have felt jubilant over symbolic victories like the Asghar Khan case (PLD 2013 SC 1) and, more recently, the judgment in the Faizabad dharna case (PLD 2019 SC 318) authored by Chief Justice Qazi Faez Isa, without appreciating the fact that panacea for such a dysfunction lay in a carefully crafted roadmap spanning years and not in passing judgments spelling out rights and duties of the protagonists in black and white.

According to Paul van Zyl, a South African lawyer and co-founder of the International Center for Transitional Justice, New York, who also served as Executive Secretary of the TRC from 1995 to 1998, ‘new democracies emerging from periods of massive and/or systematic violations of human rights are unable, for a combination of practical and political reasons, to prosecute more than a tiny percentage of those responsible for such human rights abuse.’ Van Zyl argues that for such a transition to take place, an amnesty for the perpetrators of such abuses is a pivotal component for the way forward, which formed the bedrock of the TRC.

Compare that with what the Pakistani political system and its current state of dysfunctionality look like from the outside. Like South Africa, Pakistan’s criminal justice system suffers from a chronic lack of capacity and inability to prosecute those responsible for consistently undermining its political system, hence the need for a locally tailored truth commission. Moreover, the former White government and its security forces would never have allowed the transition to a democratic order had its members and intelligence operatives been exposed to arrest, prosecution and imprisonment sans an element of amnesty. Similarly, for such a transition to take place here in Pakistan, an incentive in terms of a legally binding amnesty is the need of the hour.

In fact, the absence of an amnesty to set the ball rolling, as opposed to our courts intermittently attempting to punish those responsible, has understandably not yielded any results at all, and the mistrust and chasm between the civilians and the military have widened, which currently seems transformed into an existential crisis of gargantuan proportions.

Pakistan needs to adopt a creative approach to the problem in order to find a solution which is, above all, workable. Having said that, the proposed truth commission may also not look exactly like the South African “travelling roadshow” promising heart-wrenching real-time performances of grief and anger from victims’ families, which could only produce debilitating disempowerment for those affected instead of charting a way forward and, to use a euphemism, make a new start.

On account of non-compliance with its past judgments, especially those in Asghar Khan and Faizabad dharna cases and various other factors, the Supreme Court in the Suo Moto case regarding 6 Islamabad High Court Judges’ letter may well choose to pass a direction to the executive to enact similar legislation paving the way for a truth commission to be formed which may be entrusted with not only negotiating the mode and substance of such a transition but also its contours, functions and tenure, amongst other things.