April-May will be harvest time in India. Politicians will reap electoral yields in the 2024 general elections; peasants will collect crops sown in the annual Rabi season. Interestingly, both are on the roads, rallying support and registering protests for their respective causes. While political leaders are leading their quinquennial poll campaigns, farmers have relaunched their agitation against the BJP-ruled central government with their demands.

The farmer agitation is in fact a continuation of their protests 2020-21, when they had blocked roads from neighboring Haryana, Punjab and UP into the capital New Delhi. They were demanding annulment of three farm laws passed by the BJP government. Farmers had deemed these laws as eating into the profits of their assiduously cultivated crops by not making Minimum Support Price (MSP) – the minimum sale price of the crops set by the central government – a guarantee, and opening routes to corporate houses to directly purchase farm produce. In fact, companies belonging to businessmen like Gautam Adani had begun building their granaries in rural hinterlands for such purchases.

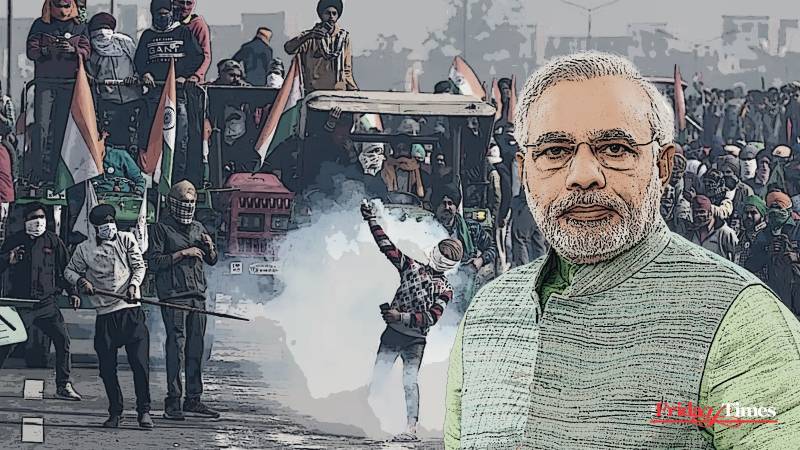

The three-month-long farmer protests ended when Prime Minister Narendra Modi announced the scrapping of the three newly-legislated farm laws.

The center had also promised to bring in new laws in consultation with various farmer organizations and address all their key demands. However, as months passed and elections to several provincial assemblies took place, including those in Punjab and UP, where the farmer agitation had originated and had maximum effect, the government put the issue of the MSP and other peasant demands in cold storage.

Thousands of farmers have dug in their heels at various entry and bordering points between Haryana, Punjab, Delhi and UP. The farmers are said to be protesting across 59 locations, mostly in Punjab and Haryana.

Early in the first week of February, Bhawant Singh Mann, the chief minister of Punjab and who is from Arvind Kejriwal’s Aam Aadmi Party (AAP), tried to mediate on behalf of farmers with Union ministers Arjun Munda, the Minister for Agriculture, Piyush Goyal, the Minister of Commerce and Industry and Minister of Consumer Affairs and Food, and Nityanand Rai, the Minister of State for Home Affairs. Mann and his party were at the forefront of espousing the cause of the farmers and came to power having outsted the powerful Congress, highlighting the woes of farmers and widespread corruption.

Mann, however, failed to bring the two sides to the table and the farmers launched their agitation – Dilli Chalo – on February 13. Since then, thousands have dug in their heels at various entry and bordering points between Haryana, Punjab, Delhi and UP. The farmers are said to be protesting across 59 locations, mostly in Punjab and Haryana.

Till the writing of this piece, the farmers had halted their march to Delhi due to the “possibility of talks through alternative channels” and in order to avoid “facing heavy force” that might be used by the government.

The farmers’ demands and the government’s response

Present protests of farmers were started by the Kisan Mazdoor Morcha (KMM), an umbrella organization made up of over 100 farmer unions. Then, they were joined by Samyukta Kisan Morcha, another outfit consisting of hundreds of farmer unions. Farmers are pressing the Modi government with various demands, including a legal guarantee of minimum support prices (MSP) for crops, implementation of the Swaminathan Commission’s recommendations, pension for farmers and farm laborers, no hike in electricity tariff, withdrawal of police cases and “justice” for the victims of the 2021 Lakhimpur Kheri violence (Minister of State for Home Affairs Ajay Kumar Sharma’s son is the prime accused in the case), reinstatement of the Land Acquisition Act, 2013, and compensation to the families of the farmers who died during the 2020-21 agitation among other demands.

One of farmers’ demands is also that India must withdraw from the World Trade Organisation (WTO).

Right now, there is an impasse. Around five rounds of talks have produced no result, with the government fearing that giving in on the MSP might lead to increased inflation in the country. While PM Modi had evaded addressing this burning issue despite being on a public welfare project-inauguration spree, his cabinet colleagues have insisted that the government has already “increased” farmers’ income and that there is a necessity to have dialogue” to break the deadlock and clear the roads.

On February 29, the Samyukta Kisan Morcha (SKM) and Kisan Mazdoor Morcha – the two organizations leading the agitation – held a meeting to the effect and threatened the government that if it doesn’t move into action mode to address their demands, it should be ready to see farmers on Delhi’s roads.

“We have always conversed and further also we will do so to find a solution. I hope we will discuss the issue further as well. The Government of India is dedicated to the development of the agriculture sector,” Agriculture Minister Arjun Munda told reporters in New Delhi. Union Minister for Information & Broadcasting, Youth Affairs & Sports Anurag Thakur assured: “We were ready for talks when farmers held protests last time. We are ready yet again. When PM Modi talks about four castes for which his government is dedicated to work for, they are poor, women, youth and cultivators of grains (farmers). We are still giving the maximum MSP that is one of the highest such prices given to peasants in the world… These are just rumors that we will do away with MSP,” he said, while addressing a press conference.

As the farmers have been indignantly camping at the Khanauri and Shambhu points on the Punjab-Haryana border, there are talks of organizing a mahapanchayat (a huge meeting) to launch the Dilli Chalo (March to Delhi), also the official name of the agitation, in reality by walking and driving on tractors to Delhi. On February 29, the Samyukta Kisan Morcha (SKM) and Kisan Mazdoor Morcha – the two organizations leading the agitation – held a meeting to the effect and threatened the government that if it doesn’t move into action mode to address their demands, it should be ready to see farmers on Delhi’s roads. However, the government has not budged, which, in turn, has warned the farmers that if they don’t clear the roads, their passports and visas will be cancelled.

The majority of farmers protesting this time are from Punjab and they have visas to Canada, US, Australia and European countries.

A government official said on the condition of anonymity that the government seeks to modernize farming by bringing in new laws that will open the agriculture sector to market. “Unless it is done, the farmer will not be able to face the challenges of the future. They are being misled by certain organizations that are holding these protests. Don’t they themselves know that reforms are the call of our time in each and every sector?” he said.

MSP?

The Minimum Support Price (MSP) is the price that the central government fixes so that farmers stay immune to market fluctuation of rates and get a fixed lowest rate for their crops. The central government fixes MSP for 22 mandated agricultural crops - seven cereals (paddy, wheat, maize, sorghum, pearl millet, barley and madua or finger millet), five pulses (gram, toor or pigeon peas, moong or green gram, urad or black lentil, lentil), seven oilseeds (groundnut, rapeseed-mustard, soybean, sesamum, sunflower, safflower and niger) and three commercial crops (copra, cotton and raw jute). The government also establishes a Fair and Remunerative Price (FRP) for sugarcane on the basis of the recommendations of the Commission for Agricultural Costs and Prices (CACP), after considering the views of state governments, central ministries and departments concerned and other relevant factors.

A legal guarantee means that there will be legal provisions for farmers to get the MSP for all 23 crops when they sell them.

The government, in its Union Budget for 2018-19, had announced the predetermined principle to keep MSP at the levels of one-and-half times the cost of production. Accordingly, the government has increased the MSP for all mandated Kharif, Rabi and other commercial crops with a return of at least 50 per cent over all-India weighted average cost of production from the agricultural year 2018-19 onwards. A legal guarantee means that there will be legal provisions for farmers to get the MSP for all 23 crops when they sell them.

According to an article written by Dibyendu Chaudhari in the Down To Earth magazine, it is practically impossible to create a legal provision for MSP. The combined value of all crops covered under MSP, produced in 2020, was Rs 10 lakh crore. India’s total budgeted expenditure in 2023-24 is around 45 lakh crores; so, it is practically impossible to spend 10 lakh crores only to buy crops from farmers.

“However, the farmers do not sell their entire produce and use a significant portion of it for personal consumption. Though this varies from crop to crop, on average, 25 percent of the total production of these 23 crops is used for personal consumption. So, a legal guarantee means that a provision of 7.5 lakh crore rupees is to be created in the budget for purchasing agriculture products covered under MSP.

This will have a huge impact on the exchequer and other welfare and development activities won’t be possible,” Chaudhari wrote.

However, Lakhwinder Singh, a visiting professor at the Institute for Human Development, argues in favor of legal guarantee for an MSP as the peasants are demanding. “The legalization of the MSP is in the national interest. A large number of farmers sell commodities in informal markets. The government now wants to make transactions digital and formal, so this is in consonance with the government’s aim. Also, the gross fixed capital formation in the agricultural sector after the 1991 reforms has gone down tremendously. Farmers are in distress. Legalizing MSP is the answer,” he told The Hindu newspaper.

Depleted Support, Deranged Politics

When farmers protested against the central government in 2020-21, according to Kubool Qureshi, who had covered those protests, a wave of support had developed naturally. “Farmers from Punjab, Haryana, UP and Rajasthan had gathered on all borders of New Delhi. Like the Shaheen Bagh protests against the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA), the farmer protest too had caught the nation’s fancy. The national media was among them, highlighting their plight and amplifying their demands with regular headlining. Ultimately, the government gave in and three farm laws that were so pompously brought by the Modi government were withdrawn, with PM himself announcing their rollback,” said Qureshi.

However, Qureshi says, the scene in the country thereafter changed drastically. “The Congress party that had strongly backed the protests lost the assembly polls in Punjab. Similarly, the BJP recently wrested Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan and Chhattisgarh and earlier, UP in 2022, despite the fact that peasants from these states too had participated in the protests,” said Qureshi.

The farmer agitation is the largest public protest against the Modi government after the anti-CAA protests organized by Muslims.

Qureshi concludes that since the farmer protests have no electoral value, the opposition parties, especially the Congress, have avoided taking active part in it. “The opposition parties have paid only lip service thus far, and they don’t seem to want to go beyond that,” he added.

Besides diminished support from opposition parties, the farmer protests this time are limited to Punjab and Haryana, and not all farmer unions that were berserk in 2020-21 are part of the agitation in 2024.

The agitation started on February 13 and despite several rounds of police actions and one casualty, the protests are absent from media glare. The news about them, if carried at all, are buried in the inside pages.

In an interesting development in Punjab, the Congress and AAP, which are in national alliance otherwise, will fight 2024 parliamentary polls separately, leaving the issue of farmers to either side to take up.

The farmer agitation is the largest public protest against the Modi government after the anti-CAA protests organized by Muslims. “Both seem fated to fail. The CAA may soon return in the form of law in India, while farmers may return to their homes, if not by state force, by getting disgruntled of not being heard either by the government or the opposition,” said Qureshi.

There is also another dramatic denouement that some in the Delhi media circles are guessing: in order to assuage farmers and convince them to end their agitation, PM Modi may announce some surprise reliefs for farmers by touting “Modi’s guarantee” – the catchline of BJP’s 2024 campaign.