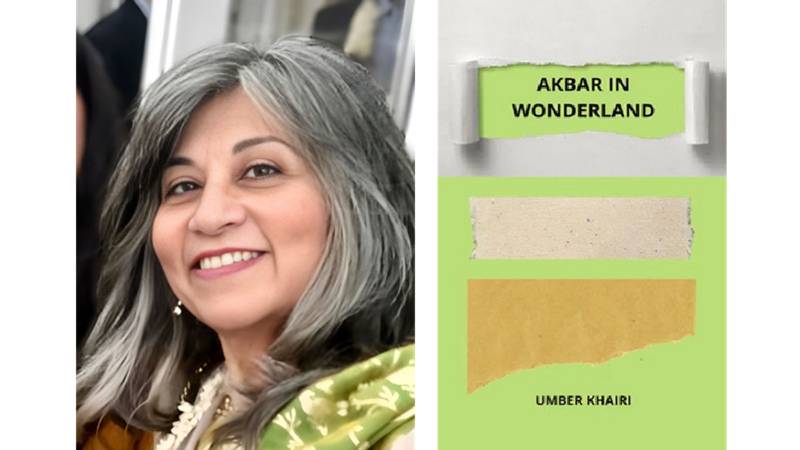

Ms Umber Khairi’s sincerely written book, Akbar in Wonderland, highlights the important point that journalists the world over are at risk. The better they become at their profession, the greater the risk. It shouldn’t have to be this way, but unfortunately it is. Moringa/Reverie Publishing are also to be commended on realising how vital this issue is to society—again, important across the globe. The premise of Khairi’s novel, set in Pakistan in the early 1990s, is that an earnest and well-meaning journalist, Akbar Hussain, is happy about editing a newsmagazine for his paper, regardless of the fact that his colleague Irfan can be a somewhat trying (if not downright obtuse) person. Khairi’s delineation of matters about which she (herself an experienced and acclaimed journalist) is knowledgeable is on point, especially a semi-hilarious scene where Irfan expects Akbar and his team (which contains a couple of very competent female journalists) to kowtow to a couple of junior interns who think too much of themselves. Akbar is right in noting that at the age of 29, he himself is hardly in his dotage, and Irfan’s desire to infuse the paper with “young blood” comes across as ridiculous to him. Irfan turns out to be much more problematic later, but that was to be expected; he is stupid at best and unethical at worst.

But the book is far more sinister, naturally, and readers will be left genuinely saddened at the end. The PM and Spouse whom “Everybody knows” (a mantra introduced and repeatedly quoted in the early portion of the text) are responsible for shady and criminal activities (in spite of lack of tangible proof). They are removed from their high-level posts, partly because of media efforts. However, Akbar’s friend Zed, a doggedly persistent journalist, explores the underpinnings of the story further. Without divulging intricate details of the plot I will now simply state that eventually a major figure in the book, central to the plot, ends up losing his life. His body is found bundled into a car, with his aghast friends being unable to initially comprehend why he would have committed suicide.

Khairi proceeds to whitewash the positions of the PM and Spouse, which I personally consider to be a generous and noble move, because people in positions of power are all too often blamed by “Everybody” for things that they sometimes have no clue about, let alone an active hand in. It turns out that the murder was not something that either of those figures was responsible for—instead a sinister Pakistani agency had a major role to play in having it committed because it suited their agenda. An agenda which partially involved maligning two people whom “Everybody” believes to be less than ethical, often dangerous.

Umber Khairi deserves a resounding pat on her back for sincerity and one looks forward to her learning from her mistakes

This is where the novel flounders, a point that I consider to be as tragic as the killing itself. Apparently this highly powerful agency, whom one would logically expect to be very thorough in its machinations (certainly they appear to have the manpower and influence to be so) made error upon error when it came to framing the murder as a suicide, and covering their own tracks. Even the somewhat naïve protagonist ends up having suspicions about the crime, and trust me he isn’t the sharpest tool in the shed although his basic writing abilities are never in question. All I can say is that no major agency that seriously and committedly tracks a person of interest and then ends up killing him or her, would be clueless about which hand he or she writes with (especially in a day prior to the point where cell-phone use became widespread; journalists took notes by hand more often then). Moreover, no self-respecting murderer with ample time on his hands would have let a victim’s floor-mats go unsearched—even Hollywood thrives on showing how criminal agencies turn one’s personal spaces inside-out when looking for suspicious material. Especially given the point that the killing in this novel was effected to clamp down on sensitive information. Oddly all this reminds me of Johnny Depp’s famous line in the gory but brilliant film From Hell, where Jack the Ripper feeds grapes to hapless prostitutes before killing them. Depp notes: “No one in Whitechapel, no matter what their trade, could afford grapes.” Grapes were an expensive delicacy at that time. Everyone would have known that, especially the police force operating in Whitechapel.

Speaking of “expensive," this novelistic move (of hastily cobbling together the abovementioned murder) proves costly for the author. For what results from this haste is the subsequent failure of the plot to whitewash the images of the PM and Spouse. I will be generous and say that “suspension of disbelief” (Coleridge’s famous phrase) is required at points in order for a reader to enjoy a novel. But if lack of plausibility becomes too extreme (and alas, it does in this case) the entire authorial agenda of a novelist tends to suffer. Be that as it may, Umber Khairi deserves a resounding pat on her back for sincerity and one looks forward to her learning from her mistakes. The novel was a debut after all, and Khairi is to be commended for giving us an entertaining view of “Akhbaar” in Wonderland!