As Pakistan’s public debt nears Rs24 trillion and its economic problems assume alarming proportions, the ‘failure’ of democratic dispensations is hot news again. This failure, critics argue, is aptly reflected in the below par economic performance of the country, primarily measured by Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth rates, in the last decade. This leads them to conclude that democracy has not done much for Pakistan’s economy.

Such arguments and augmented statistics provide considerable verbal and intellectual ammunition to supporters of military and technocratic regimes. In lieu of this, there is a need to revisit this debate and analyse what literature tells us about the link between democracy and economic growth. The first part of this article concentrates on the academic aspects of this debate, while the second part revisits the debate in terms of Pakistan’s economic performance.

First of all, this is a very old debate dating to the times of Plato and Aristotle. They debated the form of government that could bring the greatest benefit to the lot of men. Two millennia afterwards, the debate still rages on. In terms of whether democracy imparts a positive impact on economic growth or not, consensus eludes the world of economics since research has come up with varying conclusions.

This particular kind of research can be divided into two broad categories: cross-country comparisons and panel data studies. The cross country comparisons, for example, Barro (1996) and Wacziarg (2001), have mostly concluded that the link between democracy and economic growth is not very strong. However, recent panel data studies like that of Dani Rodrik (2005) and Darren Acemoglu (2014) suggest otherwise, that democracy does indeed have a sizeable impact on economic growth. For example, the post-Soviet/Warsaw Pact transition to democracy in Eastern Europe resulted in better economic performance. These studies were given further credence by the publication of two recent books by Jared Rubin (Rulers, Religion and Riches) and Joel Mokyr (Culture of Growth), concluding that as the masses became part of the system through parliamentary democracy, the benefits of economic activity started to gradually trickle down to them, a mechanism that was absent in the times of kings and feudalism.

Now that we have done a quick tour of the intellectual debate surrounding the topic, it is time to turn our attention to Pakistan and delve deeper into the question of democracy and Pakistan’s economy. The following lines make an effort to parse through the muddied waters and present a dispassionate analysis.

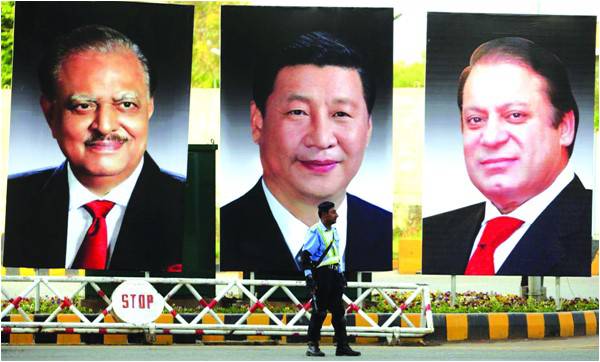

The first, and the most grievous, error that we encounter in this debate is the recourse to GDP growth rates as the sole criterion for making judgment calls. This is especially true of supporters of military regimes who latch onto this criterion. It is wrong to frame this debate in terms of GDP growth rates since, by themselves, they don’t convey much. A government can spend on building roads, bridges, buildings and other infrastructure, which will ultimately show up as additions to GDP. Still, it tells us nothing about utilization rates, ownership, modes of financing, and maintenance expenditures. Why are these important rather than just the growth rate number? To underscore this point, consider projects being completed under the China Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC). Given that these projects involve $60 billion or more, the amount will surely prop up Pakistan’s GDP. Yet this information does not convey the important point that all projects are being debt-financed, meaning that Pakistan will have to pay back more than $60 billion in the future, adding substantively to the debt burden. This additional debt burden, however, will never show up in GDP numbers. Thus, merely citing GDP growth rates is a poor criterion to use in this debate.

The second important consideration is the sources of economic growth. It is here that ‘confluence of happy circumstances’ argument comes to the fore, explaining a large part of the high growth rates under military regimes. Governments under military dictators (except Yahya Khan) were the beneficiaries of large-scale Western aid, which helped not only create much needed fiscal space but also helped reschedule loans, maintain foreign reserves and access loans at favorable rates. The Southeast Asia Treaty Organisation (SEATO) and Central Treaty Organisation (CENTO) factor in the 1960s, the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in the 1980s, and 9/11 in the 2000s provided the background for generous aid flows that created additional space for expenditure on growth enhancing areas.

Such luck usually evaded the democratic regimes, who had to face dwindling aid flows and problems left behind by the ‘high growth’ areas. For example, not many recognize that the uncontrollable genie of circular debt was set in motion during the Musharraf years. Between 2008 and 2013, Pakistan’s economy had to face two massive external shocks in the form of history’s largest floods and peak oil prices that proved to be significant drain on resources, and thus culling possibility of expenditures on GDP growth.

Last, but not the least, it is a clever ploy to quote growth rates in average in order to hide the notable variations. If we especially parse the ‘high growth eras’ we would notice a striking reality: the growth rates with and without flow of aid are different. The growth rates, for example, before the war in 1965 and after that, when American aid began dwindling, are different. Similarly, the growth rates between 1999-2003 and after that, when western financial aid came in large droves, are noticeably different. In short, what this tells us is that Pakistan’s economic performance has been critically dependent upon foreign aid, whether in the form of bilateral aid or through donor institutions like International Monetary Fund.

Should the above explanation lead us to exonerate democratic dispensations of their relatively poor record when it comes to economic management? Not at all! In fact, if the performance of the economy under military regimes was built substantially upon western largesse, the politicians also had their chances but showed poor grasp of economic management and made poor decisions. Three examples of such chances can be cited from 1950s, 1970s and under the present setup. The early 1950s and 1970s saw a quantum leap in exports due to the outbreak of Korean War, leading to sky high raw material prices, and a huge devaluation of the rupee, in the aftermath of separation of East Pakistan. Between 2013 and 2018, oil prices crashed to historic lows due to the great recession and invention of shale oil, enabling Pakistan to save billions of dollars in oil import bills.

Yet all these opportunities were squandered without any effort to maintain the advantage bestowed upon by fortune. Strategic blunders like taking recourse to rental power (2008-2013), needlessly contracting expensive debt just to claim ‘records’ (2013-2018) and keeping rupee artificially high are but a few instances of economic mismanagement.

So, what can we conclude about democracy and economic growth? Economic growth, we need to understand, can be achieved under any system.

Democracy by itself is not bad for the Pakistani economy. In fact, it is not even about military versus the democrats, but about enhancing the quality of life through sound economic management, which is achievable under any system. Unfortunately, in Pakistan’s case, both the civilian and military dispensations have been failures at that, some more than the others.

Such arguments and augmented statistics provide considerable verbal and intellectual ammunition to supporters of military and technocratic regimes. In lieu of this, there is a need to revisit this debate and analyse what literature tells us about the link between democracy and economic growth. The first part of this article concentrates on the academic aspects of this debate, while the second part revisits the debate in terms of Pakistan’s economic performance.

First of all, this is a very old debate dating to the times of Plato and Aristotle. They debated the form of government that could bring the greatest benefit to the lot of men. Two millennia afterwards, the debate still rages on. In terms of whether democracy imparts a positive impact on economic growth or not, consensus eludes the world of economics since research has come up with varying conclusions.

This particular kind of research can be divided into two broad categories: cross-country comparisons and panel data studies. The cross country comparisons, for example, Barro (1996) and Wacziarg (2001), have mostly concluded that the link between democracy and economic growth is not very strong. However, recent panel data studies like that of Dani Rodrik (2005) and Darren Acemoglu (2014) suggest otherwise, that democracy does indeed have a sizeable impact on economic growth. For example, the post-Soviet/Warsaw Pact transition to democracy in Eastern Europe resulted in better economic performance. These studies were given further credence by the publication of two recent books by Jared Rubin (Rulers, Religion and Riches) and Joel Mokyr (Culture of Growth), concluding that as the masses became part of the system through parliamentary democracy, the benefits of economic activity started to gradually trickle down to them, a mechanism that was absent in the times of kings and feudalism.

Now that we have done a quick tour of the intellectual debate surrounding the topic, it is time to turn our attention to Pakistan and delve deeper into the question of democracy and Pakistan’s economy. The following lines make an effort to parse through the muddied waters and present a dispassionate analysis.

Economic growth can be achieved under any system. Democracy by itself is not bad for the Pakistani economy

The first, and the most grievous, error that we encounter in this debate is the recourse to GDP growth rates as the sole criterion for making judgment calls. This is especially true of supporters of military regimes who latch onto this criterion. It is wrong to frame this debate in terms of GDP growth rates since, by themselves, they don’t convey much. A government can spend on building roads, bridges, buildings and other infrastructure, which will ultimately show up as additions to GDP. Still, it tells us nothing about utilization rates, ownership, modes of financing, and maintenance expenditures. Why are these important rather than just the growth rate number? To underscore this point, consider projects being completed under the China Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC). Given that these projects involve $60 billion or more, the amount will surely prop up Pakistan’s GDP. Yet this information does not convey the important point that all projects are being debt-financed, meaning that Pakistan will have to pay back more than $60 billion in the future, adding substantively to the debt burden. This additional debt burden, however, will never show up in GDP numbers. Thus, merely citing GDP growth rates is a poor criterion to use in this debate.

The second important consideration is the sources of economic growth. It is here that ‘confluence of happy circumstances’ argument comes to the fore, explaining a large part of the high growth rates under military regimes. Governments under military dictators (except Yahya Khan) were the beneficiaries of large-scale Western aid, which helped not only create much needed fiscal space but also helped reschedule loans, maintain foreign reserves and access loans at favorable rates. The Southeast Asia Treaty Organisation (SEATO) and Central Treaty Organisation (CENTO) factor in the 1960s, the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in the 1980s, and 9/11 in the 2000s provided the background for generous aid flows that created additional space for expenditure on growth enhancing areas.

Such luck usually evaded the democratic regimes, who had to face dwindling aid flows and problems left behind by the ‘high growth’ areas. For example, not many recognize that the uncontrollable genie of circular debt was set in motion during the Musharraf years. Between 2008 and 2013, Pakistan’s economy had to face two massive external shocks in the form of history’s largest floods and peak oil prices that proved to be significant drain on resources, and thus culling possibility of expenditures on GDP growth.

Last, but not the least, it is a clever ploy to quote growth rates in average in order to hide the notable variations. If we especially parse the ‘high growth eras’ we would notice a striking reality: the growth rates with and without flow of aid are different. The growth rates, for example, before the war in 1965 and after that, when American aid began dwindling, are different. Similarly, the growth rates between 1999-2003 and after that, when western financial aid came in large droves, are noticeably different. In short, what this tells us is that Pakistan’s economic performance has been critically dependent upon foreign aid, whether in the form of bilateral aid or through donor institutions like International Monetary Fund.

Should the above explanation lead us to exonerate democratic dispensations of their relatively poor record when it comes to economic management? Not at all! In fact, if the performance of the economy under military regimes was built substantially upon western largesse, the politicians also had their chances but showed poor grasp of economic management and made poor decisions. Three examples of such chances can be cited from 1950s, 1970s and under the present setup. The early 1950s and 1970s saw a quantum leap in exports due to the outbreak of Korean War, leading to sky high raw material prices, and a huge devaluation of the rupee, in the aftermath of separation of East Pakistan. Between 2013 and 2018, oil prices crashed to historic lows due to the great recession and invention of shale oil, enabling Pakistan to save billions of dollars in oil import bills.

Yet all these opportunities were squandered without any effort to maintain the advantage bestowed upon by fortune. Strategic blunders like taking recourse to rental power (2008-2013), needlessly contracting expensive debt just to claim ‘records’ (2013-2018) and keeping rupee artificially high are but a few instances of economic mismanagement.

So, what can we conclude about democracy and economic growth? Economic growth, we need to understand, can be achieved under any system.

Democracy by itself is not bad for the Pakistani economy. In fact, it is not even about military versus the democrats, but about enhancing the quality of life through sound economic management, which is achievable under any system. Unfortunately, in Pakistan’s case, both the civilian and military dispensations have been failures at that, some more than the others.