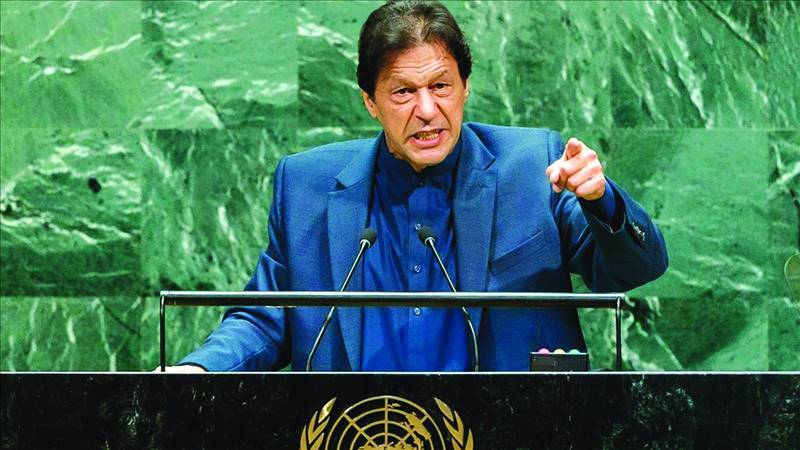

Prime Minister Imran Khan has returned to the country after addressing the United Nations General Assembly, but the public discussion on his address and all that he said, how he said it and what all he did not say continues. This discussion is likely to continue for some time.

This interest in his address is not unexpected. After all, it was PM Khan’s first address at the UN and it took place within weeks of India’s annexation of Kashmir. Demanding Kashmiris’ right to self-determination has always been a central theme of Pakistani leaders’ UN speeches, but Khan himself had created some hype about his own. “I will present Kashmir’s case at the UN like no one ever did before,” he had thundered a week before embarking on the journey.

As if to give dramatic effect, Khan also emphatically shut the doors on any dialogue with India. “There will be no talks with India until it restores the special status of Kashmir and annuls the revocation of Article 370,” he had said and barred Prime Minister Modi from using Pakistani airspace for flying to Germany. Brave gestures before brave words in New York.

Pakistanis by their natural disposition are emotional and many are easily carried away by rhetoric. Trolls also played a role in building up the rhetoric around the UNGA address: how “great” it was, how world leaders were “stunned,” how the mention of Islamophobia “left Muslim diplomats with moist eyes,” how he spoke “extempore and without notes,” how he spoke “for over 45 minutes compared with ten minutes allowed to other world leaders’ and how there was “pin drop silence” during his speech.

Speeches are important, no doubt, but they are just talks and cannot replace actions. A true measure of speech or any other act lies in the results achieved. History of the General Assembly is replete with emphatic and moving speeches. Cuba’s Fidel Castro, PLO’s Yasser Arafat, Venezuela’s Hugo Chavez, Libya’s Qaddafi and many more made impassioned speeches, pouring scorn on the US or on Israel or on this or that country and its leaders. But if today anyone who strode on the world stage is remembered, it is because of his decisions and actions and not because of the rhetoric in the UN.

Khan started his address on the right note namely, environment degradation and global climate change. Understandably, the world is far more concerned about it than about Kashmir. But here Khan’s chief weapon should have been truth, rather than unrealistic and seemingly false claims.

Khan declared to cheering diplomats that he had planted one billion trees in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. He promised to plant 10 billion trees in the country. After all applause dies down, someone may closely look at the claims and Khan might end up losing credibility at the world stage.

By the rule of the thumb, trees are spaced five meters apart. Thus, only 40,000 trees can be planted in a one square kilometer area. A billion trees would require 25,000 square kilometres of land. Pakhtunkhwa’s total land area (including buildings, roads, forests, housing) is less than 75,000 square kilometres. Is it conceivable that one-third of its land mass has already been covered with forests in just one year? Likewise, planting 10 billion in the country requires 250,000 square kilometers of land mass. If trees indeed are planted on this area, it would mean that over 28 percent of the country’s 881,000 square kilometres has been brought under forest cover. Given that the current forest-to-land ratio is less than five percent, doesn’t it look like too tall a claim?

In terms of real action there has been dismal failure. PM Khan had publicly claimed support of 58 countries over Kashmir. It was declared that Pakistan will move a resolution in the UN Human Rights Council (UNHRC) on rights violations in Kashmir. To do this, the support of only 16 countries at the Council was required on September 19. However, none came forward and Pakistan failed to move the planned resolution in the Council.

The prime minister’s remarks at various forums like the Council of Foreign Relations and in the media, whether right or wrong, certainly did not help Pakistan. How would remarks like Pakistan Army training Al Qaeda militants or that Durand Line was an artificially drawn line, even if true, help advance Pakistan’s case and cause? In diplomacy, stated positions are not abandoned without quid pro quo.

But the worst part was brandishing of nuclear weapons before the international gathering. It was perhaps for the first time that a country possessing nuclear weapons actually threatened the world community on a global forum. This has never happened before. It only gave the Indian delegate the opportunity to accuse Khan of ‘brinkmanship’ and devoid of statesmanship. Abruptly replacing Maleeha Lodhi in an unceremonious manner with hawkish ex-Ambassador at the UN soon after returning to Islamabad will only further reinforce the perception of brandishing nuclear weapons too often.

A likely net result of this brinkmanship will be that jittery Khan would have unwittingly earned the unspoken, unwritten hostility of the world.

A statesman would know that the defining characteristic underlying national struggles today is not what it was in the middle of the last century. Then the use of militancy by subjugated nations as a tool for overthrowing colonial rule was accepted and even applauded. Today, armed intrusion, particularly from across the borders is condemned as the greatest scourge namely, terrorism. This point was totally lost on PM Khan when he brandished nuclear weapons in the UN.

The writer is a former senator

This interest in his address is not unexpected. After all, it was PM Khan’s first address at the UN and it took place within weeks of India’s annexation of Kashmir. Demanding Kashmiris’ right to self-determination has always been a central theme of Pakistani leaders’ UN speeches, but Khan himself had created some hype about his own. “I will present Kashmir’s case at the UN like no one ever did before,” he had thundered a week before embarking on the journey.

As if to give dramatic effect, Khan also emphatically shut the doors on any dialogue with India. “There will be no talks with India until it restores the special status of Kashmir and annuls the revocation of Article 370,” he had said and barred Prime Minister Modi from using Pakistani airspace for flying to Germany. Brave gestures before brave words in New York.

Pakistanis by their natural disposition are emotional and many are easily carried away by rhetoric. Trolls also played a role in building up the rhetoric around the UNGA address: how “great” it was, how world leaders were “stunned,” how the mention of Islamophobia “left Muslim diplomats with moist eyes,” how he spoke “extempore and without notes,” how he spoke “for over 45 minutes compared with ten minutes allowed to other world leaders’ and how there was “pin drop silence” during his speech.

Speeches are important, no doubt, but they are just talks and cannot replace actions. A true measure of speech or any other act lies in the results achieved. History of the General Assembly is replete with emphatic and moving speeches. Cuba’s Fidel Castro, PLO’s Yasser Arafat, Venezuela’s Hugo Chavez, Libya’s Qaddafi and many more made impassioned speeches, pouring scorn on the US or on Israel or on this or that country and its leaders. But if today anyone who strode on the world stage is remembered, it is because of his decisions and actions and not because of the rhetoric in the UN.

A statesman would know that the defining characteristic underlying national struggles today is not what it was in the middle of the last century

Khan started his address on the right note namely, environment degradation and global climate change. Understandably, the world is far more concerned about it than about Kashmir. But here Khan’s chief weapon should have been truth, rather than unrealistic and seemingly false claims.

Khan declared to cheering diplomats that he had planted one billion trees in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. He promised to plant 10 billion trees in the country. After all applause dies down, someone may closely look at the claims and Khan might end up losing credibility at the world stage.

By the rule of the thumb, trees are spaced five meters apart. Thus, only 40,000 trees can be planted in a one square kilometer area. A billion trees would require 25,000 square kilometres of land. Pakhtunkhwa’s total land area (including buildings, roads, forests, housing) is less than 75,000 square kilometres. Is it conceivable that one-third of its land mass has already been covered with forests in just one year? Likewise, planting 10 billion in the country requires 250,000 square kilometers of land mass. If trees indeed are planted on this area, it would mean that over 28 percent of the country’s 881,000 square kilometres has been brought under forest cover. Given that the current forest-to-land ratio is less than five percent, doesn’t it look like too tall a claim?

In terms of real action there has been dismal failure. PM Khan had publicly claimed support of 58 countries over Kashmir. It was declared that Pakistan will move a resolution in the UN Human Rights Council (UNHRC) on rights violations in Kashmir. To do this, the support of only 16 countries at the Council was required on September 19. However, none came forward and Pakistan failed to move the planned resolution in the Council.

The prime minister’s remarks at various forums like the Council of Foreign Relations and in the media, whether right or wrong, certainly did not help Pakistan. How would remarks like Pakistan Army training Al Qaeda militants or that Durand Line was an artificially drawn line, even if true, help advance Pakistan’s case and cause? In diplomacy, stated positions are not abandoned without quid pro quo.

But the worst part was brandishing of nuclear weapons before the international gathering. It was perhaps for the first time that a country possessing nuclear weapons actually threatened the world community on a global forum. This has never happened before. It only gave the Indian delegate the opportunity to accuse Khan of ‘brinkmanship’ and devoid of statesmanship. Abruptly replacing Maleeha Lodhi in an unceremonious manner with hawkish ex-Ambassador at the UN soon after returning to Islamabad will only further reinforce the perception of brandishing nuclear weapons too often.

A likely net result of this brinkmanship will be that jittery Khan would have unwittingly earned the unspoken, unwritten hostility of the world.

A statesman would know that the defining characteristic underlying national struggles today is not what it was in the middle of the last century. Then the use of militancy by subjugated nations as a tool for overthrowing colonial rule was accepted and even applauded. Today, armed intrusion, particularly from across the borders is condemned as the greatest scourge namely, terrorism. This point was totally lost on PM Khan when he brandished nuclear weapons in the UN.

The writer is a former senator