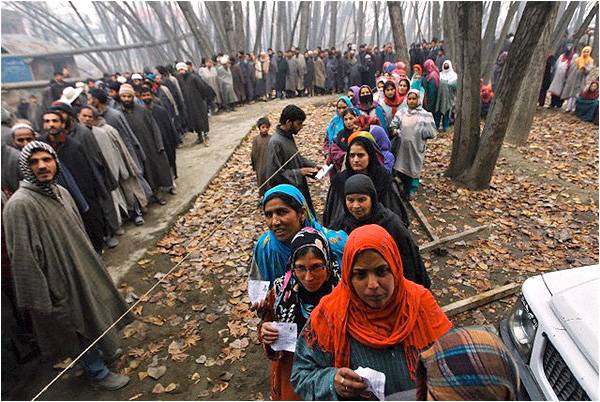

The huge turnout in the first and second phase of polling in Jammu and Kashmir has baffled many. Many people saw this as something unprecedented due to the fact that people in the state in general and in Kashmir valley in particular had locked horns with the Indian state over the resolution of the political dispute. And reposing faith in the electoral system is seen by many as rejection of separatism in Kashmir. It is a fact that the separatists who have been spearheading the movement for the right to self-determination had called for a boycott and people who voted did not pay heed to it.

I remember covering the first election after the insurgency in Kashmir. General elections were held in India in May 1996, and the National Conference, the premier regional party, had boycotted them making the restoration of Kashmir’s autonomy a precondition to contesting the polls. This threw a major challenge towards New Delhi, but they went ahead and announced that Jammu and Kashmir would have elections after a gap of seven years. It was to set the stage for the Assembly elections that followed in September that year. I, along with other colleagues, was very keen to report the electoral exercise. And not taking any chances of being stopped en route either by protesters or the army, we decided to reach Baramulla a day ahead. All of us stayed at the house of Late Ghulam Jeelani Baba, the longtime and versatile stringer for many newspapers. His warm hospitality helped all of us engage in lively discussions dealing with the pros and cons of the elections and the likely turnout.

As we began our day, the atmosphere was tense and there was no sign of people taking part in the elections. A heavy deployment of troops had turned the election areas into garrisons.

It appeared as an alien exercise not only because of the ubiquitous presence of the Indian army men on the streets but also the presence of employees from other states such as Bihar, Madhya Pradesh and Uttar Pradesh, who conducted the elections. Local government employees had stayed away from election duties.

We were just waiting for the first “brave voter” to appear on the scene. At many booths we waited for a long time until the columns of army moved. They literally dragged people to the polling stations forcing them to repose faith in the Indian democracy. There was resistance but ultimately there was a turnout at the end. This was the scene almost everywhere in Kashmir. Most of the people managed to stay away. But elections were held.

Three months later, the Government of India took the plunge to hold assembly elections in the state. Not much had changed, except that the pro-government Ikhwan had an upper hand as far as the security environment was concerned. Delhi was seriously lacking legitimacy in and people had put up a stiff resistance. The National Conference feared being pushed out of the political arena forever, so it did not wait and jumped into the fray without asking for autonomy. If sources are to be believed, Farooq Abdullah was told that a senior separatist leader was ready to lead the polls and he would be installed as chief minister. This enticing approach made him rethink his options, and he decided to contest the polls. An exercise almost similar to the one in May was repeated. Again, government employees were imported from other states and with an element of coercion the turnout went up.

At many booths, people openly said they were caught between three guns – that of militants, counter-insurgents and the Indian Army, and they wanted to get rid of that. So they needed a civilian face at the top. Thus the NC came to power.

Over a period of time, elections started acquiring legitimacy and people came out on their own to vote. People’s involvement with political parties and their stakes in matters of governance in the shape of getting government jobs, contracts and other benefits increased. These sops, which came in various forms, worked and New Delhi was able to bribe the people so all the elections held after 2002 saw a significant turnout.

The “huge” turnout witnessed in first and second phase is nothing about which people should be surprised. This is simply people’s urge to be part of governance, to improve their quality of life and make their representatives accountable.

The turnout must not be mixed with the larger political discourse in Kashmir. If the elections are a referendum or authenticate accession, why would people take to streets in tens of thousands in 2008, 2009 and 2010? Why would we see thousands of people attending funeral prayers of militants? Even in the second phase of elections held on December 2, a boycott was witnessed in parts of Kashmir. How would that be interpreted then? People in those areas not only boycotted the elections but also chanted pro-freedom slogans.

Boycotting elections has been in fact an inalienable part of Kashmir politics right since 1947. In 1951, when the Constituent Assembly was to be chosen, 73 out of 75 members were elected unopposed. The boycott was called by Muslim Conference in Kashmir and Parija Parishad in Jammu. All the elections from 1955 to 1972 were boycotted by major political players.

However, one thing that needs to be underlined is that the separatists should also introspect and rethink their strategy in view of the rejection of the boycott call by many. It does not mean that they have been rejected, but that they must make the argument that elections are for governance and have nothing to do with right to self- determination, which is at the centre of their future course of action. In fact, those who voted have offered a face saving to the separatists by drawing this distinction.

Asked about their decision to vote, a group of enthusiastic youth said although they were supporters of the call for freedom, they wanted to see a particular candidate come to power. “After that, we will lay our lives for Geelani sahib. We protested in the 2008 and the 2010 agitations, and our friend Irfan was killed by the army in 2013. But we want justice to be done with us,” one of them added. This quote is enough to understand the dilemma of the people of Kashmir.

The author is a journalist based in Srinagar, and the editor of English daily Rising Kashmir

I remember covering the first election after the insurgency in Kashmir. General elections were held in India in May 1996, and the National Conference, the premier regional party, had boycotted them making the restoration of Kashmir’s autonomy a precondition to contesting the polls. This threw a major challenge towards New Delhi, but they went ahead and announced that Jammu and Kashmir would have elections after a gap of seven years. It was to set the stage for the Assembly elections that followed in September that year. I, along with other colleagues, was very keen to report the electoral exercise. And not taking any chances of being stopped en route either by protesters or the army, we decided to reach Baramulla a day ahead. All of us stayed at the house of Late Ghulam Jeelani Baba, the longtime and versatile stringer for many newspapers. His warm hospitality helped all of us engage in lively discussions dealing with the pros and cons of the elections and the likely turnout.

As we began our day, the atmosphere was tense and there was no sign of people taking part in the elections. A heavy deployment of troops had turned the election areas into garrisons.

It appeared as an alien exercise not only because of the ubiquitous presence of the Indian army men on the streets but also the presence of employees from other states such as Bihar, Madhya Pradesh and Uttar Pradesh, who conducted the elections. Local government employees had stayed away from election duties.

We were just waiting for the first “brave voter” to appear on the scene. At many booths we waited for a long time until the columns of army moved. They literally dragged people to the polling stations forcing them to repose faith in the Indian democracy. There was resistance but ultimately there was a turnout at the end. This was the scene almost everywhere in Kashmir. Most of the people managed to stay away. But elections were held.

All the elections from 1955 to 1972 were boycotted by major political players in Kashmir

Three months later, the Government of India took the plunge to hold assembly elections in the state. Not much had changed, except that the pro-government Ikhwan had an upper hand as far as the security environment was concerned. Delhi was seriously lacking legitimacy in and people had put up a stiff resistance. The National Conference feared being pushed out of the political arena forever, so it did not wait and jumped into the fray without asking for autonomy. If sources are to be believed, Farooq Abdullah was told that a senior separatist leader was ready to lead the polls and he would be installed as chief minister. This enticing approach made him rethink his options, and he decided to contest the polls. An exercise almost similar to the one in May was repeated. Again, government employees were imported from other states and with an element of coercion the turnout went up.

At many booths, people openly said they were caught between three guns – that of militants, counter-insurgents and the Indian Army, and they wanted to get rid of that. So they needed a civilian face at the top. Thus the NC came to power.

Over a period of time, elections started acquiring legitimacy and people came out on their own to vote. People’s involvement with political parties and their stakes in matters of governance in the shape of getting government jobs, contracts and other benefits increased. These sops, which came in various forms, worked and New Delhi was able to bribe the people so all the elections held after 2002 saw a significant turnout.

The “huge” turnout witnessed in first and second phase is nothing about which people should be surprised. This is simply people’s urge to be part of governance, to improve their quality of life and make their representatives accountable.

The turnout must not be mixed with the larger political discourse in Kashmir. If the elections are a referendum or authenticate accession, why would people take to streets in tens of thousands in 2008, 2009 and 2010? Why would we see thousands of people attending funeral prayers of militants? Even in the second phase of elections held on December 2, a boycott was witnessed in parts of Kashmir. How would that be interpreted then? People in those areas not only boycotted the elections but also chanted pro-freedom slogans.

Boycotting elections has been in fact an inalienable part of Kashmir politics right since 1947. In 1951, when the Constituent Assembly was to be chosen, 73 out of 75 members were elected unopposed. The boycott was called by Muslim Conference in Kashmir and Parija Parishad in Jammu. All the elections from 1955 to 1972 were boycotted by major political players.

However, one thing that needs to be underlined is that the separatists should also introspect and rethink their strategy in view of the rejection of the boycott call by many. It does not mean that they have been rejected, but that they must make the argument that elections are for governance and have nothing to do with right to self- determination, which is at the centre of their future course of action. In fact, those who voted have offered a face saving to the separatists by drawing this distinction.

Asked about their decision to vote, a group of enthusiastic youth said although they were supporters of the call for freedom, they wanted to see a particular candidate come to power. “After that, we will lay our lives for Geelani sahib. We protested in the 2008 and the 2010 agitations, and our friend Irfan was killed by the army in 2013. But we want justice to be done with us,” one of them added. This quote is enough to understand the dilemma of the people of Kashmir.

The author is a journalist based in Srinagar, and the editor of English daily Rising Kashmir