In this author’s last piece in these pages, it was suggested that our former colonial rulers had brought the extraordinary innovations of a professional military and a professional bureaucracy to the Subcontinent. This highly effective “steel frame” of administration was the secret of the success of colonial rule. More to the present point, this army and this civil service were powerful assets that the departing British perforce left behind for our political leaderships to use in order to defend and govern the new countries that emerged from the former British India. Properly managed and effectively utilised, these assets could conceivably have been used to build prosperous and strong post-colonial states.

But this has not happened – at least, not in Pakistan. For much of this nation’s life, instead of parliaments and political leaderships determining and directing the work of these professionals, the machinery of the state has been turned upside down. And soldiers, with the bureaucracy in tow, often found themselves in charge.

It needs to be noted that, like other professionally run outfits that place a premium on executive effectiveness, any military detests indecision, incompetence, uncertainty, nonconformity, and unnecessary shades of grey. In this, it is not unlike corporate executives or bankers, who can usually be counted among those who applaud the periodic military incursions into statecraft.

Allow me to wind the clock back to 1954. General Mohammed Ayub Khan, the first Pakistani Commander-in-Chief of the Army of this young republic thought as follows on the night of the 4th of October, 1954 (as revealed in his exceedingly readable autobiography Friends not Masters):

“I was staying...at a hotel in London...on my way to the United States. It was a warmish night and I could not sleep...I was pacing up and down the room when I said to myself, ‘Let me put down my ideas in a military fashion: what is wrong with the country and what can be done to put things right.’ I approached the question much in the manner of drawing up a military appreciation: what is the problem, what are the factors involved, and what is the solution...? So I sat down at my desk and started writing.”

Please note the open and candid manner in which this officer presumed to outline an entirely political plan for his country’s future. His impatience with the political authorities and their continual failure to act towards objectives that he felt were self-evident are clearly expressed in his book.

One can scarcely fault the future Field Marshal for his attitude. Even seven years after Independence, the Constituent Assembly had failed to frame a Constitution. The nation was blessed, on the one side, with the kind of politicos regarded as ‘pro-government’: mostly rural potentates, quite content to fly flags on their cars, receive special attention at the local Katcheri, and play obscure games of shifting around baradari alliances. On the other side, the ‘opposition-wallahs’ were populist spell-binders or left-wing ideologues, mostly from the then East Wing, or a handful of bearded proponents of religious ideologies. None of these seemed to feel any urgent need for legislation or meaningful action.

Military officers, accustomed to executive action and effective administration, as well as the British-trained civilian bureaucrats, were bound to become impatient with politicos such as these.

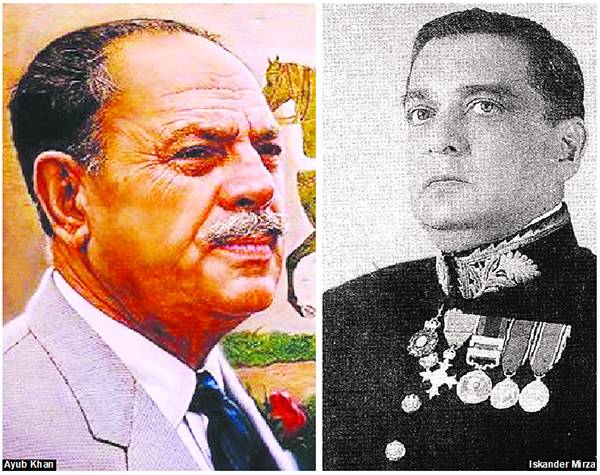

Less than three weeks after that warm October night in London, top bureaucrat Governor-General Malik Ghulam Mohammad acted. With (as a newspaper of the time put it) “a general to the left of him and a general to the right”, he ordered the dissolution of the Constituent Assembly and the sacking of the government. The new government, formed under a chastened Prime Minister, included General Mohammed Ayub Khan, serving C-in-C and author of the diary entry we have been discussing, as Defence Minister. The other (formerly) uniformed member of the government was Interior Minister Major-General (R) Iskander Mirza, later to become G-G and then President.

A busy time was to follow, as those who had brought about this civil-military coup proceeded to actualise Ayub’s midnight diary notes. Pakistan became a member of the US-sponsored SEATO defence pact and thereafter of the Baghdad Pact (subsequently CENTO), thus making this country a strategic element in the American cordon sanitaire around the USSR and China, and ensuring the inflow of weaponry, technology, and funds to Pakistan. American aid for the economy, under the PL480 and US-IAD programmes, began arriving with the Prime Minister walking down to the harbour in Karachi to receive the first consignment, with a sign around his neck thanking America. The provinces of the Western Wing were amalgamated into the ‘One Unit’ province of West Pakistan, with its capital at Lahore. The Tamizuddin Khan case was briskly contested, leading to the infamous judgement by Justice Munir. A new Constituent Assembly was created, which finally framed a Constitution for Pakistan.

However, barely two years after the promulgation of the Constitution, it was abrogated by President Iskander Mirza, who declared martial law and appointed General Ayub Khan as Prime Minister.

With Ayub subsequently overthrowing Mirza, the military was in full control and in a position to more completely reorder and reorganise matters to ensure that policies were correctly directed and that things got done. Which policies and actions were ‘correct’, was, of course, not in doubt either. The minds of our good Field Marshal and those around him were not sympathetic to the complexities of competing political ideals and the many grey areas in between. Ayub Khan promulgated his own new Constitution. In defiance of already firmly established preferences for the parliamentary system, the 1962 document provided for an all powerful executive President...and one unfettered by such concepts as Separation of Powers. Instead of a popularly elected Legislature or direct elections for the President, this Constitution provided for an electoral college of 80,000 ‘basic democrats’ to vote for the parliamentarians and for the Head of State and Government. Where the ethnic diversity and divided geography of the country obviously called for federal arrangements, the 1962 Basic Law was unitary in structure. Everything was highly centralised in the person of the Field Marshal.

As any student of politics could have told, the 1962 document was unworkable. It collapsed with its author’s departure from political office.

And these are the conclusions I wish to leave with my reader: It is not that there is anything particularly ‘wrong’ with the bureaucratic or military mindset. In fact, its preoccupation with clear objectives and effective action is very attractive. But to have it frame a complex document like a national Constitution – a task for which it is simply not educationally or psychologically equipped – was a gross abdication of responsibility on the part of the political leadership of the time.

Let’s face it: because incompetent or do-nothing or internally divided parliaments failed to satisfy the people’s demands, they left a kind of ‘vacuum of effectiveness’, into which stepped the more action-oriented, better organised institutions: the civil bureaucracy and the military. The only exceptions to this pattern of ineffectiveness among ‘civilian’ dispensations, in the view of this writer, were the government of Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto during its extraordinary first couple of years and the activism occasionally displayed by Nawaz Sharif.

On whom, then, should the long suffering people place the blame for these failures? The servants of the state, i.e. its armed forces, bureaucracy, and judiciary? Or the leaders of the state, its parliamentarians and political masters, with their senseless political games and the stench of corruption surrounding them?

But this has not happened – at least, not in Pakistan. For much of this nation’s life, instead of parliaments and political leaderships determining and directing the work of these professionals, the machinery of the state has been turned upside down. And soldiers, with the bureaucracy in tow, often found themselves in charge.

It needs to be noted that, like other professionally run outfits that place a premium on executive effectiveness, any military detests indecision, incompetence, uncertainty, nonconformity, and unnecessary shades of grey. In this, it is not unlike corporate executives or bankers, who can usually be counted among those who applaud the periodic military incursions into statecraft.

Military officers, accustomed to executive action and effective administration, as well as the British-trained civilian bureaucrats, were bound to become impatient with politicos

Allow me to wind the clock back to 1954. General Mohammed Ayub Khan, the first Pakistani Commander-in-Chief of the Army of this young republic thought as follows on the night of the 4th of October, 1954 (as revealed in his exceedingly readable autobiography Friends not Masters):

“I was staying...at a hotel in London...on my way to the United States. It was a warmish night and I could not sleep...I was pacing up and down the room when I said to myself, ‘Let me put down my ideas in a military fashion: what is wrong with the country and what can be done to put things right.’ I approached the question much in the manner of drawing up a military appreciation: what is the problem, what are the factors involved, and what is the solution...? So I sat down at my desk and started writing.”

Please note the open and candid manner in which this officer presumed to outline an entirely political plan for his country’s future. His impatience with the political authorities and their continual failure to act towards objectives that he felt were self-evident are clearly expressed in his book.

One can scarcely fault the future Field Marshal for his attitude. Even seven years after Independence, the Constituent Assembly had failed to frame a Constitution. The nation was blessed, on the one side, with the kind of politicos regarded as ‘pro-government’: mostly rural potentates, quite content to fly flags on their cars, receive special attention at the local Katcheri, and play obscure games of shifting around baradari alliances. On the other side, the ‘opposition-wallahs’ were populist spell-binders or left-wing ideologues, mostly from the then East Wing, or a handful of bearded proponents of religious ideologies. None of these seemed to feel any urgent need for legislation or meaningful action.

Military officers, accustomed to executive action and effective administration, as well as the British-trained civilian bureaucrats, were bound to become impatient with politicos such as these.

Less than three weeks after that warm October night in London, top bureaucrat Governor-General Malik Ghulam Mohammad acted. With (as a newspaper of the time put it) “a general to the left of him and a general to the right”, he ordered the dissolution of the Constituent Assembly and the sacking of the government. The new government, formed under a chastened Prime Minister, included General Mohammed Ayub Khan, serving C-in-C and author of the diary entry we have been discussing, as Defence Minister. The other (formerly) uniformed member of the government was Interior Minister Major-General (R) Iskander Mirza, later to become G-G and then President.

A busy time was to follow, as those who had brought about this civil-military coup proceeded to actualise Ayub’s midnight diary notes. Pakistan became a member of the US-sponsored SEATO defence pact and thereafter of the Baghdad Pact (subsequently CENTO), thus making this country a strategic element in the American cordon sanitaire around the USSR and China, and ensuring the inflow of weaponry, technology, and funds to Pakistan. American aid for the economy, under the PL480 and US-IAD programmes, began arriving with the Prime Minister walking down to the harbour in Karachi to receive the first consignment, with a sign around his neck thanking America. The provinces of the Western Wing were amalgamated into the ‘One Unit’ province of West Pakistan, with its capital at Lahore. The Tamizuddin Khan case was briskly contested, leading to the infamous judgement by Justice Munir. A new Constituent Assembly was created, which finally framed a Constitution for Pakistan.

However, barely two years after the promulgation of the Constitution, it was abrogated by President Iskander Mirza, who declared martial law and appointed General Ayub Khan as Prime Minister.

With Ayub subsequently overthrowing Mirza, the military was in full control and in a position to more completely reorder and reorganise matters to ensure that policies were correctly directed and that things got done. Which policies and actions were ‘correct’, was, of course, not in doubt either. The minds of our good Field Marshal and those around him were not sympathetic to the complexities of competing political ideals and the many grey areas in between. Ayub Khan promulgated his own new Constitution. In defiance of already firmly established preferences for the parliamentary system, the 1962 document provided for an all powerful executive President...and one unfettered by such concepts as Separation of Powers. Instead of a popularly elected Legislature or direct elections for the President, this Constitution provided for an electoral college of 80,000 ‘basic democrats’ to vote for the parliamentarians and for the Head of State and Government. Where the ethnic diversity and divided geography of the country obviously called for federal arrangements, the 1962 Basic Law was unitary in structure. Everything was highly centralised in the person of the Field Marshal.

As any student of politics could have told, the 1962 document was unworkable. It collapsed with its author’s departure from political office.

And these are the conclusions I wish to leave with my reader: It is not that there is anything particularly ‘wrong’ with the bureaucratic or military mindset. In fact, its preoccupation with clear objectives and effective action is very attractive. But to have it frame a complex document like a national Constitution – a task for which it is simply not educationally or psychologically equipped – was a gross abdication of responsibility on the part of the political leadership of the time.

Let’s face it: because incompetent or do-nothing or internally divided parliaments failed to satisfy the people’s demands, they left a kind of ‘vacuum of effectiveness’, into which stepped the more action-oriented, better organised institutions: the civil bureaucracy and the military. The only exceptions to this pattern of ineffectiveness among ‘civilian’ dispensations, in the view of this writer, were the government of Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto during its extraordinary first couple of years and the activism occasionally displayed by Nawaz Sharif.

On whom, then, should the long suffering people place the blame for these failures? The servants of the state, i.e. its armed forces, bureaucracy, and judiciary? Or the leaders of the state, its parliamentarians and political masters, with their senseless political games and the stench of corruption surrounding them?