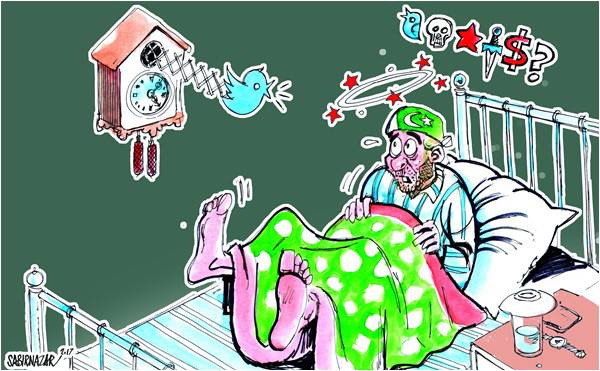

True to form, US President Donald Trump has welcomed the new year with a barrage of threatening tweets against his favourite targets in North Korea, Iran, Palestine and the US Media. Pakistan now has the dubious distinction of being added to this Quixotic list of “enemies”. It stands accused of “lies and deceit”, of playing “double games”, of gobbling up $33 billion in the last fifteen years, of “harbouring terrorists”, etc. “No more”, warns President Trump, unless Pakistan is ready to “do more” to help America.

Understandably, the public reaction in Pakistan has been shrill. The country has been awash with anti-Americanism for many years. Thankfully, the government’s tone is measured. It is “disappointed” by President Trump’s damning allegations. Indeed, Islamabad claims it has paid a very high price in men and material fighting the war against terrorism but it will not compromise on its long-term national security interests when they conflict with short-term American goals.

Are US-Pakistan relations about to rupture with severe consequences for both, but especially for Pakistan?

In his autobiographical books “The Art of the Deal” and “Time to Get Tough”, published years ago, President Trump boasts about how he used bullying tactics to clinch his most successful business deals. Clearly, he thinks the same strategy will work in the White House. But the Iranians, North Koreans and Palestinians have not yet been cowed down and the US media is still baying for his blood. How will Pakistan fare?

Much depends on how President Trump intends “to sort out” Pakistan. Clearly, the carrot of $33b hasn’t worked. So the stick may be brandished. He has cut $255m from the military component of the Kerry-Lugar-Berman aid package. Earlier, the US withheld an amount of $350 million from the Coalition Support Program reimbursements to Pakistan. But this is no big deal, says Miftah Ismail, the new finance minister, “it’s just a day’s expenditure for the Pakistan government”.

The US may conceivably take other steps to “punish” Pakistan. It could lean on international finance institutions to tighten the screws on Pakistan at a time when it is faced with a developing balance of payments crisis. It could sanction Pakistani exports to the US. It could deal a blow to Pakistani business transactions by restricting access to SWIFT, the global provider of critical and secure financial messaging services. It could put Pakistani military officials and institutions with alleged links to banned or terrorist organisations on its sanctions list and restrict their international movements and freeze their assets. It could expand the theatre of drone operations inside Pakistan. It might even be tempted to attack the “safe havens” of the Haqqani network on the Pak-Afghan border. But each action would be precipitous, with unintended adverse consequences for both Pakistan and America.

“Pakistan”, thunders army chief Qamar Javed Bajwa, “is impregnable”. The air force chief says he will shoot down any drones venturing into Pakistan territory. The bluster is political necessity in the face of a bully. But the reality is harsh, whatever the worth of US allegations.

Pakistan has never been more divided and weak internally than it is now. The mainstream politicians are at each other’s throats, inviting constitutional deviation. The military is manipulating favourites. The judiciary is reeling from the backlash of its own judgments. The economy is tanking. Balochistan and FATA on the periphery are in turmoil. The “foreign hand” of India and Afghanistan continues to foment trouble. No one can say with any confidence that the general elections will be held on time and a smooth transfer of power will take place. Let us admit it: a nation at war with itself can hardly put up a decent defense against a certified global bully.

Ex-Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif is out of power not because he is inordinately more corrupt than everyone else in office but because he has chosen to call a spade a spade. He has challenged the political hegemony of the Miltablishment whose national security doctrines – including jumping in and out of bed with America – have brought Pakistan to a sorry pass where it is regionally alienated and internationally isolated. Clutching at Pakistan’s all-weather friend China will not erase or replace this reality. Mr Sharif has recently alluded to the price he is paying for attempting to question this “national security” paradigm. “It is time,” he says, “to put our house in order… there is a need to examine our character and actions with sincerity…we need to understand why our narrative is dismissed…if it is ignored and termed against the national interest, this is nothing but self-deception that has already led to the fragmentation of Pakistan once before”.

Foreign intervention in disunited and failing states can trigger mass upheavals, chaos and disintegration. The Arab “spring” has become a withering winter and Middle-Eastern nation states have been reduced to rubble amidst the specter of “militant Islam”. This unintended consequence of foreign intervention is now raising its ugly head over the Pakistani horizon. Ruling establishments in America and Pakistan should beware their proposed actions and reactions.

Understandably, the public reaction in Pakistan has been shrill. The country has been awash with anti-Americanism for many years. Thankfully, the government’s tone is measured. It is “disappointed” by President Trump’s damning allegations. Indeed, Islamabad claims it has paid a very high price in men and material fighting the war against terrorism but it will not compromise on its long-term national security interests when they conflict with short-term American goals.

Are US-Pakistan relations about to rupture with severe consequences for both, but especially for Pakistan?

In his autobiographical books “The Art of the Deal” and “Time to Get Tough”, published years ago, President Trump boasts about how he used bullying tactics to clinch his most successful business deals. Clearly, he thinks the same strategy will work in the White House. But the Iranians, North Koreans and Palestinians have not yet been cowed down and the US media is still baying for his blood. How will Pakistan fare?

Much depends on how President Trump intends “to sort out” Pakistan. Clearly, the carrot of $33b hasn’t worked. So the stick may be brandished. He has cut $255m from the military component of the Kerry-Lugar-Berman aid package. Earlier, the US withheld an amount of $350 million from the Coalition Support Program reimbursements to Pakistan. But this is no big deal, says Miftah Ismail, the new finance minister, “it’s just a day’s expenditure for the Pakistan government”.

The US may conceivably take other steps to “punish” Pakistan. It could lean on international finance institutions to tighten the screws on Pakistan at a time when it is faced with a developing balance of payments crisis. It could sanction Pakistani exports to the US. It could deal a blow to Pakistani business transactions by restricting access to SWIFT, the global provider of critical and secure financial messaging services. It could put Pakistani military officials and institutions with alleged links to banned or terrorist organisations on its sanctions list and restrict their international movements and freeze their assets. It could expand the theatre of drone operations inside Pakistan. It might even be tempted to attack the “safe havens” of the Haqqani network on the Pak-Afghan border. But each action would be precipitous, with unintended adverse consequences for both Pakistan and America.

“Pakistan”, thunders army chief Qamar Javed Bajwa, “is impregnable”. The air force chief says he will shoot down any drones venturing into Pakistan territory. The bluster is political necessity in the face of a bully. But the reality is harsh, whatever the worth of US allegations.

Pakistan has never been more divided and weak internally than it is now. The mainstream politicians are at each other’s throats, inviting constitutional deviation. The military is manipulating favourites. The judiciary is reeling from the backlash of its own judgments. The economy is tanking. Balochistan and FATA on the periphery are in turmoil. The “foreign hand” of India and Afghanistan continues to foment trouble. No one can say with any confidence that the general elections will be held on time and a smooth transfer of power will take place. Let us admit it: a nation at war with itself can hardly put up a decent defense against a certified global bully.

Ex-Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif is out of power not because he is inordinately more corrupt than everyone else in office but because he has chosen to call a spade a spade. He has challenged the political hegemony of the Miltablishment whose national security doctrines – including jumping in and out of bed with America – have brought Pakistan to a sorry pass where it is regionally alienated and internationally isolated. Clutching at Pakistan’s all-weather friend China will not erase or replace this reality. Mr Sharif has recently alluded to the price he is paying for attempting to question this “national security” paradigm. “It is time,” he says, “to put our house in order… there is a need to examine our character and actions with sincerity…we need to understand why our narrative is dismissed…if it is ignored and termed against the national interest, this is nothing but self-deception that has already led to the fragmentation of Pakistan once before”.

Foreign intervention in disunited and failing states can trigger mass upheavals, chaos and disintegration. The Arab “spring” has become a withering winter and Middle-Eastern nation states have been reduced to rubble amidst the specter of “militant Islam”. This unintended consequence of foreign intervention is now raising its ugly head over the Pakistani horizon. Ruling establishments in America and Pakistan should beware their proposed actions and reactions.