In 2016 the apprehension was that 2017 would be a repeat of what Kashmir suffered.

That year Kashmir was entirely locked down in unprecedented unrest that lasted six months. The slogan of “Azaadi” reverberated through its streets amid a return to the cycle of civilian killings with the darkest moments being when the pellet gun was used. And indeed, the fears for 2017 proved well placed. The violence reignited the “romance” of the gun with scores of young locals joining militant ranks.

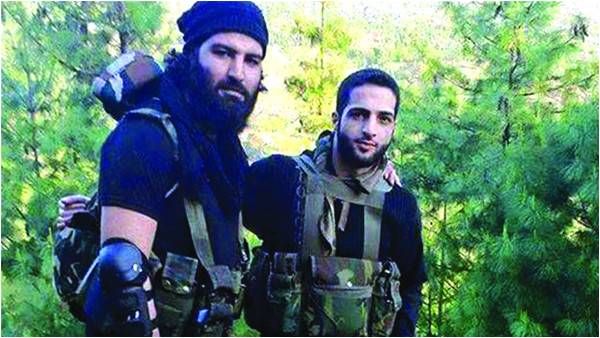

The latest example of this attraction was Fardeen Khandey, a 16-year-old boy from Tral, South Kashmir, who ended his 10-month tryst with militancy on the last day of the year in the fidayeen (suicide) attack on a Central Reserve Police Force camp in Awantipora. Five Central Reserve men, including one native Kashmiri Muslim, were killed as were Fardeen’s associate Manzoor Baba and Abdul Shakoor of Pakistan-Administered Kashmir’s Rawalakot. This attack came as a grim reminder that many minds still see violence as a solution to political conflict. And with this event, we moved into 2018.

The bloodshed

Looking back at how it unfolded, we see that 2017 was a mix of hope and despair as the killings continued to shape the headlines of the newspapers. A high number of militants and government forces lost their lives in addition to civilians who were killed by the forces—either during anti-India demonstrations or as a result of being caught in the “crossfire”.

According to the J&K Coalition of Civil Society’s annual human rights report, 450 people (124 armed forces, 217 militants, 108 civilians and one Ikhwani or pro-government militant) were killed in Jammu and Kashmir in 2017. This was a year with the highest number of killings in recent times. What is more significant is that the ratio of killings (forces-to-militants) was 2:1. This signified an increase again in casualties for the security forces. It may difficult to say whether the “quality” of militancy has changed but it is a fact that the young Kashmiris who have been joining these ranks seem to be committed and wedded to the idea of meeting their deaths.

The number of foreign militants has not gone down though the locals have now outnumbered them. Lashkar-e-Taiba and Jaish-e-Mohammad’s focus on Kashmir has led to intensified attacks amid a rising presence of Hizbul Mujahideen which was boosted after the killing of Burhan Wani in 2016. Burhan’s image as a poster boy of Kashmir’s new-age militancy attracted many young people to the cause as they perceived it.

The story of Fardeen Khandey revolves around the “glorification” that brought the armed struggle back onto the scene. Thousands of people attending the funerals, rallying behind the young militants, demonstrated a shift that society was openly “sanctioning” the path of violence. There was the exception of Majid, a young footballer from South Kashmir, who returned home on the plea of his mother, triggering a new wave of appeals from parents for their wards to shun the violence.

A new facet of local militancy has emerged with boys like Fardeen opting to become “willing martyrs”. There has been less participation from local Kashmiris in such attacks in the past (though 17-year-old Afaq surprised many when he headed with an explosives-laden car to the 15 Corps headquarters of Srinagar on April 19, 2001 and blew himself up). The year 2017 also saw the highest number of suicide attacks with militants choosing four targets, breaking a lull that had set in after 2013.

Reaction

The government boasted about its “Operation All Out” but at the same time the complexion of militancy changed as evidenced by a record number of forces being killed. The militant hit-and-run policy inflicted losses on the forces, but what also came as a jolt was the government’s hardline policy despite stiff resistance from the people.

Despondency continued to cast a shadow over the political firmament. Of late New Delhi has realized that hard power alone would not help change Kashmir. This explains the appointment of Dineshwar Sharma, a former director of the Intelligence Bureau as an interlocutor. His appointment in itself belied the Bharatiya Janata Party’s stance that Kashmir is not a political issue and only needs a military solution. But it’s been three months and he has still been unable to make a difference primarily because he has not reached out to those who represent the political dissent. Peace will remain elusive if Delhi continues to remain in denial and see Sharma’s journey to Kashmir as addressing “grievances”. There is a political dimension to the conflict with an external angle.

If Sharma shows some seriousness in approaching the problem politically and even listens to the voices that spoke of draconian laws and repressive measures, some space for dialogue could be created. But the onus in that case also lies on Kashmir’s political leadership. Another reality is that without dialogue with Pakistan no “other dialogue” can succeed in Kashmir. They are complementary and supplementary processes. But that does not mean that the Kashmir leadership should stop thinking independently.

In 2018, the violence will continue to hog the headlines as the people have not been given any reason to denounce it. Creating a political space for dialogue and not shrinking it with oppressive measures will only serve to legitimise violence and help those who have an axe to grind. This applies to both sides.

A commoner in Kashmir would like to look at 2018 with hope that can only come through the promise of dialogue, an end to the siege, better governance, justice for victims of unbridled power. Kashmir needs dignity and a treatment that is befitting its humans. Political parties have unfortunately turned them into cannon fodder.

Meanwhile, during his opening session of the state legislature on January 2, Governor NN Vohra revealed that it was not all bad news: in 2017 around 1.2 million tourists visited Kashmir valley. If a serious and sincere effort is made to ensure peace, the valley’s people would benefit and it would make their lives better. But peace can be achieved only through dignity. This is the challenge for 2018.

The writer is a senior journalist based in Srinagar (Kashmir) and can be reached at shujaat7867@gmail.com

That year Kashmir was entirely locked down in unprecedented unrest that lasted six months. The slogan of “Azaadi” reverberated through its streets amid a return to the cycle of civilian killings with the darkest moments being when the pellet gun was used. And indeed, the fears for 2017 proved well placed. The violence reignited the “romance” of the gun with scores of young locals joining militant ranks.

The latest example of this attraction was Fardeen Khandey, a 16-year-old boy from Tral, South Kashmir, who ended his 10-month tryst with militancy on the last day of the year in the fidayeen (suicide) attack on a Central Reserve Police Force camp in Awantipora. Five Central Reserve men, including one native Kashmiri Muslim, were killed as were Fardeen’s associate Manzoor Baba and Abdul Shakoor of Pakistan-Administered Kashmir’s Rawalakot. This attack came as a grim reminder that many minds still see violence as a solution to political conflict. And with this event, we moved into 2018.

The year 2017 also saw the highest number of suicide attacks with militants choosing four targets, breaking a lull that had set in after 2013

The bloodshed

Looking back at how it unfolded, we see that 2017 was a mix of hope and despair as the killings continued to shape the headlines of the newspapers. A high number of militants and government forces lost their lives in addition to civilians who were killed by the forces—either during anti-India demonstrations or as a result of being caught in the “crossfire”.

According to the J&K Coalition of Civil Society’s annual human rights report, 450 people (124 armed forces, 217 militants, 108 civilians and one Ikhwani or pro-government militant) were killed in Jammu and Kashmir in 2017. This was a year with the highest number of killings in recent times. What is more significant is that the ratio of killings (forces-to-militants) was 2:1. This signified an increase again in casualties for the security forces. It may difficult to say whether the “quality” of militancy has changed but it is a fact that the young Kashmiris who have been joining these ranks seem to be committed and wedded to the idea of meeting their deaths.

The number of foreign militants has not gone down though the locals have now outnumbered them. Lashkar-e-Taiba and Jaish-e-Mohammad’s focus on Kashmir has led to intensified attacks amid a rising presence of Hizbul Mujahideen which was boosted after the killing of Burhan Wani in 2016. Burhan’s image as a poster boy of Kashmir’s new-age militancy attracted many young people to the cause as they perceived it.

The story of Fardeen Khandey revolves around the “glorification” that brought the armed struggle back onto the scene. Thousands of people attending the funerals, rallying behind the young militants, demonstrated a shift that society was openly “sanctioning” the path of violence. There was the exception of Majid, a young footballer from South Kashmir, who returned home on the plea of his mother, triggering a new wave of appeals from parents for their wards to shun the violence.

A new facet of local militancy has emerged with boys like Fardeen opting to become “willing martyrs”. There has been less participation from local Kashmiris in such attacks in the past (though 17-year-old Afaq surprised many when he headed with an explosives-laden car to the 15 Corps headquarters of Srinagar on April 19, 2001 and blew himself up). The year 2017 also saw the highest number of suicide attacks with militants choosing four targets, breaking a lull that had set in after 2013.

2017 was a year with the highest number of killings in recent times. The ratio of killings of forces-to-militants was 2:1. This signified an increase again in casualties for the security forces

Reaction

The government boasted about its “Operation All Out” but at the same time the complexion of militancy changed as evidenced by a record number of forces being killed. The militant hit-and-run policy inflicted losses on the forces, but what also came as a jolt was the government’s hardline policy despite stiff resistance from the people.

Despondency continued to cast a shadow over the political firmament. Of late New Delhi has realized that hard power alone would not help change Kashmir. This explains the appointment of Dineshwar Sharma, a former director of the Intelligence Bureau as an interlocutor. His appointment in itself belied the Bharatiya Janata Party’s stance that Kashmir is not a political issue and only needs a military solution. But it’s been three months and he has still been unable to make a difference primarily because he has not reached out to those who represent the political dissent. Peace will remain elusive if Delhi continues to remain in denial and see Sharma’s journey to Kashmir as addressing “grievances”. There is a political dimension to the conflict with an external angle.

If Sharma shows some seriousness in approaching the problem politically and even listens to the voices that spoke of draconian laws and repressive measures, some space for dialogue could be created. But the onus in that case also lies on Kashmir’s political leadership. Another reality is that without dialogue with Pakistan no “other dialogue” can succeed in Kashmir. They are complementary and supplementary processes. But that does not mean that the Kashmir leadership should stop thinking independently.

In 2018, the violence will continue to hog the headlines as the people have not been given any reason to denounce it. Creating a political space for dialogue and not shrinking it with oppressive measures will only serve to legitimise violence and help those who have an axe to grind. This applies to both sides.

A commoner in Kashmir would like to look at 2018 with hope that can only come through the promise of dialogue, an end to the siege, better governance, justice for victims of unbridled power. Kashmir needs dignity and a treatment that is befitting its humans. Political parties have unfortunately turned them into cannon fodder.

Meanwhile, during his opening session of the state legislature on January 2, Governor NN Vohra revealed that it was not all bad news: in 2017 around 1.2 million tourists visited Kashmir valley. If a serious and sincere effort is made to ensure peace, the valley’s people would benefit and it would make their lives better. But peace can be achieved only through dignity. This is the challenge for 2018.

The writer is a senior journalist based in Srinagar (Kashmir) and can be reached at shujaat7867@gmail.com