Essentially, I am a lawyer. Politics is my passion and the television talk show I host, my hobby. Stirred, not shaken, the three mix fairly well to create a palatable sort of cocktail. In the last week or so, many of my lawyer and politician friends have been flummoxed as to why the story of a private software company awarding fake degrees and diplomas should turn Pakistan’s media scene inside out. What, they ask, is so special about the company and the alleged crime? I don’t doubt that many TFT readers are similarly bewildered. What on earth is going on, everyone seems to be asking everyone else. Friends, in simple terms, it isn’t about Axact; it isn’t about degrees; it isn’t even about the crime the company is supposed to have committed. It’s about a television channel that no one has brought into the foreground of the story.

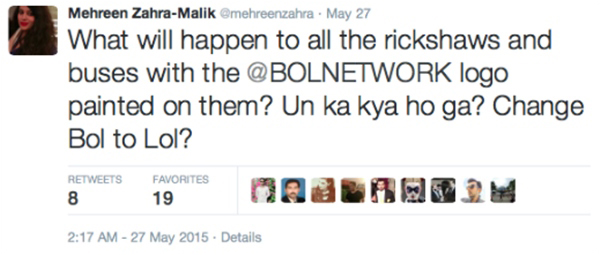

Enter Bol TV, which has been waiting in the wings for quite some time. Bol initially created a stir when it began offering huge salary packages to lure in anchors, journalists and technical team members working with other electronic media companies. When two key members of Geo TV, Kamran Khan and Azhar Abbas, left to join Bol, this upped the ante. The channel’s next high-profile catch was my friend Mubashir Luqman, which created something of a storm across the media industry. But the issue at stake is not that Bol was able to cadge many of the industry’s top people; rather, that it was evidently able to offer them mind-bogglingly large salary packages. Which begs the question: how?

The answer to this lies in the shape of Shoaib Shaikh who, with Waqas Shaikh, falls into the ‘owner’ column at Bol TV. He has claimed that Axact is (or was) Pakistan’s biggest software company with annual revenues of billions of rupees. A paltry ten million here or there every month is, therefore, really just chicken feed. All eyes now turn to Axact, where all is not well and the company is not rolling in the sort of lucre the young seth had claimed.

So who is really behind Axact or Bol? Of course, theories abound. Some suggest it was the brainchild of General Pasha – to bring in a big pro-establishment channel – and that the channel is in fact financed by the humble Pakistani taxpayer rather than the young seths of Axact. Others have suggested that the land mafia is behind it: a shadowy consortium of people with a huge kitty full of black money running the enterprise. Yet another view is that both Shoaib and Waqas are simply geniuses and able to execute big ideas at the drop of a hat.

Enter Declan Walsh, the New York Times reporter who dropped the first Axact bombshell. Until he was compelled to leave Pakistan in 2013, Declan had lived in Islamabad for years – in a city that is, for him, a second home and where he is known to every third person. His investigative report alleges that Axact was involved in running a fraudulent education business that lured unsuspecting people into its education portal and promised customers around the world degrees and diplomas at the cost of a few hundred to a few thousand dollars. The racket had grown into a Leviathan with staggering daily revenues.

But Walsh’s story contradicts previous apprehensions about the Bol network, suggesting that its main sponsors were relying on other players for capital (the Times story shows that the sponsors were – whether through fraud or business, depending on what is proven – certainly making good money).

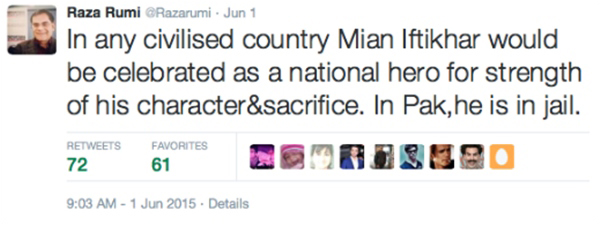

Now for a new set of conspiracy theories. How can the interior minister and the Federal Investigation Agency (FIA) have been so efficient as to not only initiate the inquiry but also conclude it in a matter of days? The FIA has, presumably, enough on its plate, but in the case of Axact, the agency’s unprecedented ‘competence’ has raised eyebrows. Some have alleged that three powerful media owners met Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif and lobbied with him to put the brakes on what may have proven a highly feared competitor. Others have their own conspiracy theories still.

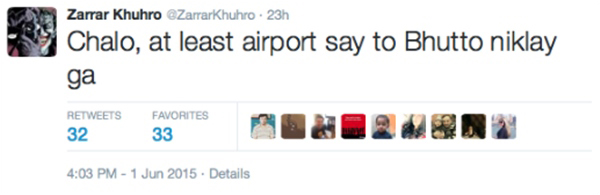

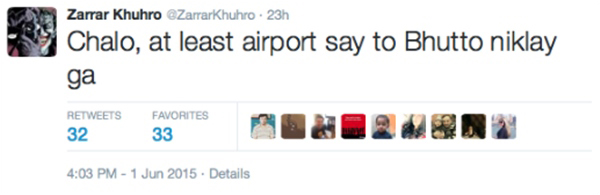

Now for the biggest question making the rounds in media circles: will Bol TV be launched or not? PEMRA has already suspended the company’s license, effectively hindering any immediate launch, but Bol has the right to go to court. If the courts suspend the PEMRA order, the channel may be launched and once it is launched – keeping Pakistani political dynamics in mind – closing it down will be very difficult. Thus, the whole game revolves around whether Bol can reach the airwaves.

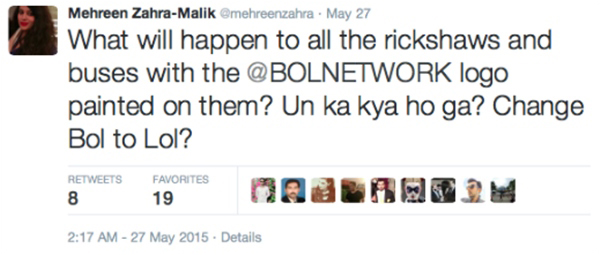

The top management has already left the group, citing reasons of ‘conscience’, although many are asking why this conscience was asleep when million-rupee packages were being accepted despite serious allegations against the Bol management. The crisis has also jeopardized the jobs of around 2,200 lower and mid-rank workers who had joined Bol. In the coming days, the media will have a sharp eye open for the fate of the Axact case and the Bol launch – and its implications for the Pakistan media scene.

Follow the author @fawadchaudhry

Enter Bol TV, which has been waiting in the wings for quite some time. Bol initially created a stir when it began offering huge salary packages to lure in anchors, journalists and technical team members working with other electronic media companies. When two key members of Geo TV, Kamran Khan and Azhar Abbas, left to join Bol, this upped the ante. The channel’s next high-profile catch was my friend Mubashir Luqman, which created something of a storm across the media industry. But the issue at stake is not that Bol was able to cadge many of the industry’s top people; rather, that it was evidently able to offer them mind-bogglingly large salary packages. Which begs the question: how?

The answer to this lies in the shape of Shoaib Shaikh who, with Waqas Shaikh, falls into the ‘owner’ column at Bol TV. He has claimed that Axact is (or was) Pakistan’s biggest software company with annual revenues of billions of rupees. A paltry ten million here or there every month is, therefore, really just chicken feed. All eyes now turn to Axact, where all is not well and the company is not rolling in the sort of lucre the young seth had claimed.

So who is really behind Axact or Bol? Of course, theories abound. Some suggest it was the brainchild of General Pasha – to bring in a big pro-establishment channel – and that the channel is in fact financed by the humble Pakistani taxpayer rather than the young seths of Axact. Others have suggested that the land mafia is behind it: a shadowy consortium of people with a huge kitty full of black money running the enterprise. Yet another view is that both Shoaib and Waqas are simply geniuses and able to execute big ideas at the drop of a hat.

Enter Declan Walsh, the New York Times reporter who dropped the first Axact bombshell. Until he was compelled to leave Pakistan in 2013, Declan had lived in Islamabad for years – in a city that is, for him, a second home and where he is known to every third person. His investigative report alleges that Axact was involved in running a fraudulent education business that lured unsuspecting people into its education portal and promised customers around the world degrees and diplomas at the cost of a few hundred to a few thousand dollars. The racket had grown into a Leviathan with staggering daily revenues.

But Walsh’s story contradicts previous apprehensions about the Bol network, suggesting that its main sponsors were relying on other players for capital (the Times story shows that the sponsors were – whether through fraud or business, depending on what is proven – certainly making good money).

Now for a new set of conspiracy theories. How can the interior minister and the Federal Investigation Agency (FIA) have been so efficient as to not only initiate the inquiry but also conclude it in a matter of days? The FIA has, presumably, enough on its plate, but in the case of Axact, the agency’s unprecedented ‘competence’ has raised eyebrows. Some have alleged that three powerful media owners met Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif and lobbied with him to put the brakes on what may have proven a highly feared competitor. Others have their own conspiracy theories still.

Now for the biggest question making the rounds in media circles: will Bol TV be launched or not? PEMRA has already suspended the company’s license, effectively hindering any immediate launch, but Bol has the right to go to court. If the courts suspend the PEMRA order, the channel may be launched and once it is launched – keeping Pakistani political dynamics in mind – closing it down will be very difficult. Thus, the whole game revolves around whether Bol can reach the airwaves.

The top management has already left the group, citing reasons of ‘conscience’, although many are asking why this conscience was asleep when million-rupee packages were being accepted despite serious allegations against the Bol management. The crisis has also jeopardized the jobs of around 2,200 lower and mid-rank workers who had joined Bol. In the coming days, the media will have a sharp eye open for the fate of the Axact case and the Bol launch – and its implications for the Pakistan media scene.

Follow the author @fawadchaudhry