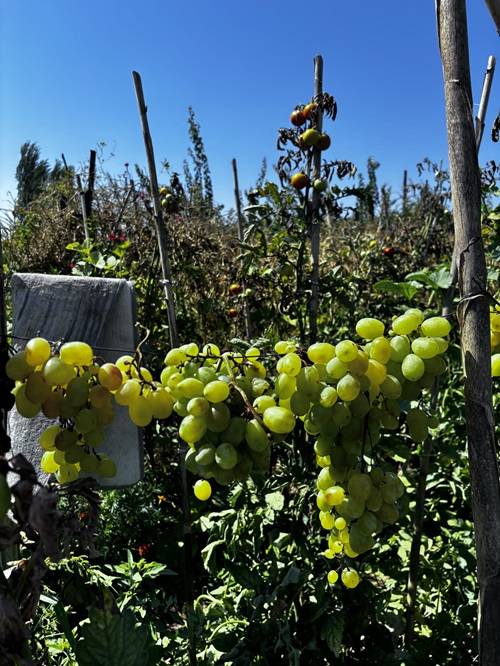

The fruit of a day trip to Iznik was a car laden with fresh peaches, grapes the size of thumbs and bottles of olive oil from the local orchards and farms.

Iznik is less than 90 km away from Istanbul and a scenic drive over motorways that cross through Mediterranean greens and blues. We went to see Iznik’s pottery, for which it is famous. Most of it, we discovered, is exported within Turkey, especially to Istanbul’s Grand Bazaar where it is overpriced but nevertheless extremely popular among tourists.

As you leave the motorway, suddenly you find yourself driving though miles of fruit orchards and olive farms. All along the wayside, farmers are selling fresh produce – in baskets or from the trees. You can’t get fruit fresher than that.

You can buy seasonal vegetables – mounds of vibrantly green peppers, fresh garlic, bright red tomatoes glowing with the Mediterranean sun. There is a shameless surfeit of fresh peaches and juicy grapes. We tried and tasted the fresh honey and cream, pickles and pomegranate molasses.

Iznik, which once had an ancient name, Nicaea, is located along the shores of a picture-perfect fresh-water blue lake in north-west Turkey. The sounds and bustle of Istanbul seem a continent away as you drive through silent olive groves and the stillness of ripening peach orchards.

The clock tower in town introduces you to the beautiful tilework for which Iznik is famous. In imperial Ottoman times, it was the centre of the tile production, which is now synonymous with the red blue and white floral motifs that distinguish Turkish tiles. At the time, the Ottoman courts valued the blue and white Chinese-style pottery, and so you can detect elements of the traditional Turkish arabesque patterns with the Chinese elements. The famous blue mosque of Istanbul is an outstanding example of this unique form of non-figurative craftmanship.

I thought about how the city had transformed over time – from the Romans and Greeks to the Ottomans, from being a producer of tiles to becoming a producer of olives, while still maintaining a rural charm and the placidity of its crystal blue waters

Ultimately, designs evolved to emphasise traditional Turkish colours – the luscious red, or the various shades of turquoise and cobalt blue and the stylized flowers that shape the tiles into a polychromatic harmony of tulips, roses and honeysuckle that still grow in abundance in Iznik’s farms.

Art forms evolve over time. So did the Ottoman tiles, famed for their non-figurative conventions – geometric designs blended with floral motifs and calligraphy. Such beauty and perfection are the best argument for the existence of the divine.

Olive groves are part and parcel of the land that lines the lakes. Along the main street of Iznik, one can buy olives in different forms – whether the pure olive oil soaps, bottles of olive oil, or olives to eat as part of a Turkish breakfast (kavahlti).

It makes sense for olives to be so plentiful in Türkiye. It is ideally located geographically. After Spain, Italy and Greece, it is the world’s fourth largest producer of olives. There is an entire line of Turkish cousin names, zetinyagli - which essentially translates to “ with olive oil.” There is even an olive oil museum in Cannakale, which I have added to my bucket list of places to visit.

A Turkish colleague, who maintains an olive orchard farm on his island as part of his hobbies, tells us that olives are not easy to grow or maintain. Typically, olive trees only begin to bear fruit 3-5 years after planting. The difference in colour between green and black olives is not between trees but how and when olives are picked when green and how they are cured.

Olives are harvested in November, and then stored in barrels with salt which helps preserve them, soften them, and accentuates their taste. Pressing olives is a tedious process. It takes almost 6 - 7 pounds of olives to yield a small 16 ounce bottle of olive oil.

Iznik, although only 90 minutes away from the city, still has a rural feel to it. The main mode of transport is still a tractor. Iznik’s local high street features outdoor museums, including the mosque and the Roman walls once built to protect the city. These city walls once stretched five kilometres – showcasing the first Turkish capital of Anatolia. This was once considered sacred by the Vatican, for in 235 AD, the doctrine of Christianity was discussed and debated by bishops from all over the world.

More recently in 2014, a Byzantine basilica dedicated to the 12th-century Saint Neophytus was discovered. It had been submerged following an earthquake in 740 AD. The building has remained under water for over 1,500 years. It is still covered by about 2 meters of water.

The ruins were revealed as a result of drought and climate change. It can be viewed only aerially. The site is being converted into an underwater museum by the government. There is something exciting to realise that, like the imperial tombs in Xian (China), many ancient ruins in Türkiye remain to be unearthed.

When walking through the streets of Iznik, I thought about how the city had transformed over time – from the Romans and Greeks to the Ottomans, from being a producer of tiles to becoming a producer of olives, while still maintaining a rural charm and the placidity of its crystal blue lakes and waters.

Marcus Garvey once wrote that a people without the knowledge of their past history, origin and culture is like a tree without roots. The roots of modern Iznik’s olive trees lie deep in its history.