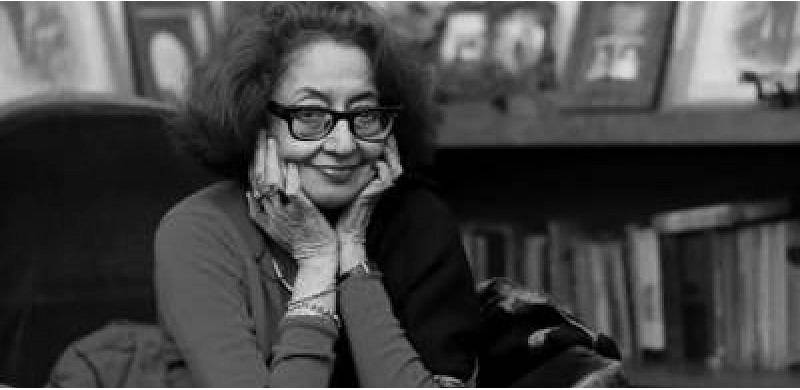

In 1947, as the British left the Indian Subcontinent, having divided it into two countries, many Indians and Pakistanis couldn’t digest the reality of partition. That momentous event had shattered the shared syncretic history and culture that spanned many centuries between Hindus and Muslims. Celebrated Urdu author, Qurratulain Hyder — endearingly called Ainee Apa by admirers — channeled her own heartbreak as well as her feudal moorings into an illustrious repertoire.

Like many characters in her books, Hyder also witnessed the traumatic events that destroyed the confluence of linguistic, cultural, and religious diversity in pre-independence India and Pakistan.

Ainee Apa’s magnum opus Aag Ka Darya (River of Fire) chronicles the decades during which those traditions coalesced to form the subcontinent’s pluralistic ethos. Towards the end, there is an Indian Muslim protagonist who reluctantly migrates to Pakistan.

However, he doesn’t feel at home in his new homeland.

Hyder’s works eloquently portray the trials and tribulations of aristocratic Muslims like herself who transplanted themselves onto Pakistani soil. Two years after Aag Ka Darya was published, she returned to India from Karachi, Pakistan, where she had moved at the time of partition.

Published in 1989 and translated by Saleem Kidwai some three decades later, her last novel Chandni Begum also revolves around the crème de la crème of North Indian Muslims.

More so the ones who stayed back after independence.

Back Among Her Own

For almost 20 years after her homecoming, she worked in Mumbai as a journalist. Ainee Apa then moved back to her home state of UP in the late 70s-early 80s. There she lived among co-religionists and saw how they fared 40 years after 1947. That too, as the Ram Janambhoomi movement, a harbinger of the precariousness currently felt by the country’s largest minority, gained steam.

Just a few years after returning to Noida, UP, the festering Ayodhya row turned what was once a hub of Hindu-Muslim syncretism into a hotbed of communal hatred.

Compared to the South, there isn’t much of a middle class among the North’s Muslims as they generally tend to be either affluent or downtrodden. The milieu of characters within the Teen Katori House epitomize this small privileged class up north that has some aristocratic tendencies, good and bad

Chandni Begum centered around two well-off, feudal Lucknowi households, the Red Rose House and Teen Katori House, from the 1950s to the years preceding the 1992 Babri Masjid demolition. Primarily through the lenses of those families, the book is a socio-cultural study of North India and its Muslims 40 years after independence.

Like Aag Ka Darya, Chandni Begum demands its readers’ attention as characters’ subtle emotions and actions drive the narrative throughout a four decade timeframe. Yet, within this character-driven plot are many distinct themes.

A Wafer-Thin, (Non-Titular) Character Driven Plot

However, the Red Rose inhabitants aren’t a stereotypical noble family. Qambar, the communist youngster, doesn’t have his way with servants and eschews the infamous debaucheries of the landed gentry. Nor does he yearn for times where feudal decadence reigned supreme. Alhamdu Bi, the servant, holds the same status for him as his own mother, Badarunnisa. The Ali family also personifies the nobility’s positive traits, like cultural refinement, etiquette, and grace. They exhibit none of the gentry’s snobbery or exploitative ways, which progressive writers like Ismat Chughtai and Munshi Premchand primarily focused on.

Munshi Bhavani Shankar Sokhta, the loyal secretary to his father Barrister Azhar, is like a paternal uncle. Their estate houses a temple for Sokhta and a mosque. Hence, Red Rose not only symbolizes the composite culture of pre-partition India, but how secular leaders like Pandit Nehru and Maulana Azad sought to uphold it after independence.

After Qambar’s parents die, a class war ravages this egalitarian household due to Bela, a non-feudal, Panchgani-educated woman who hails from a family of mirasis (traditional singers who provide entertainment on special occasions).

Class Conflict

Qambar Miyan’s trusting nature, Marxist leanings, and Bela’s machinations drive the former into the latter’s arms. Unfortunately, she doesn’t treat this idealistic, “woke” spouse well, even when he could have married someone of his ilk like Safiya from Teen Katori House. Instead, she goes about inflicting revenge on Qambar for the way other nobles treated her family as nothing but low-caste entertainers.

Bela is educated and beautiful, but lacks the finesse that women of Qambar’s background possess. These noble begums need not be moneyed, like Safiya of the Teen Katori House, with whom Qambar was engaged during his childhood. They can be like the novel’s titular character, a woman with a landed lineage minus the material possessions. Though not wealthy, she is someone with a sophisticated temperament that a convent education can’t cultivate.

Even today, such notions of being born and raised in a superior or inferior socioeconomic class hold sway among people as they choose potential (life) partners. Bela redecorates Red Rose by removing its feudal vestiges to make the house more “modern.” She also squanders the financial and physical inheritance of Azhar Ali’s and Badarunnissa’s only son. In the meantime, after losing her mother, who was promised by Badarunnissa that Chandni Begum would marry Qambar, a jobless Chandni Begum arrives at Red Rose. As a love triangle blooms between Chandni Begum, Bela, and Qambar Ali, Bela shooes away her rival back to her life of misery at Teen Katori.

Tragedy strikes as the three die in a fire that engulfs Red Rose. This ends any hope of a Qambar-Chandni Begum romance that would ensure a Red Rose’s refined ways.

On the other hand, the erosion of such culture among the Teen Katori sisters their subsequent generation is gradual and spans 40 years. The progeny of Safiya, Zareena, and Parveena loses touch with many of their traditions. These include their mother tongue Urdu along with other sartorial, exquisite qualities of their forefathers’ etiquette.

As this generation loses the nawabi grace, Chandni Begum’s memory looms large after her death. The Katori house sisters express regret at how they badly treated someone of their own landed ilk. Chandni Begum might not have the possessed their flamboyance and opulence, but she did possess many aspects of their elegant demeanours.

A Harbinger for Today’s India

Hyder doesn’t just utilize her signature symbolism to embody the trajectory of a certain stratum of northern Muslims. After Red Rose burns down, its charred remains symbolize the communally splintered state of a free Indian subcontinent.

Like India, Red Rose lived through religious partition and experienced many communal flare-ups afterwards. Oblivious to the fact that Sokhta and his temple co-existed harmoniously with Ali’s mosque, local Hindus naturally claim “their mandir”, while Muslims do the same with “their masjid.” Today in many bylanes of India, a mandir and masjid side by side are sometimes fodder for conflict. Hyder saw how such disputes would chip away at India’s secular identity. Yes, the prolonged Babri Masjid case may have finally been settled in late 2019. However, similar, if not identical, disputes emerged in Mathura and Varanasi, Uttar Pradesh.

The Split Indo-Pak Family Syndrome

Besides religious communities and places of worship that existed right by each other, many Muslim families were also divided in 1947. Parveena is one character who migrates to Pakistan.

Married and settled in Karachi, she also points out how Pakistanis don’t have to face certain dilemmas that their “Indian” family members do. Through this “Pakistani” family member, Hyder also depicts how the migration of elite families and a dearth of educated Muslim men prompts professional, qualified women from the community to marry outside their religion.

Though, by no means, does Ainee Apa demonize interfaith marriage.

In a telling moment, she has a crucial conversation with, Zareena, and Safiya about the toxic bonds of colonialism that unite South Asians. Safiya, who runs a convent, says, “…if the English-medium schools’ names don’t have the word convent in them, no one will have their kids admitted there…even in Karachi, every nook and corner has a ‘convent.’ ” Yes, the language does provide more socioeconomic mobility, but this dialogue proves that India and Pakistan suffer from this colonial hangover of English.

The language still continues to be a marker of someone’s supposed intelligence and background.

The Plight of (North) Indian Muslims

Compared to the South, there isn’t much of a middle class among the North’s Muslims as they generally tend to be either affluent or downtrodden. The milieu of characters within the Teen Katori House epitomize this small privileged class up north that has some aristocratic tendencies, good and bad. Yet the generation after Safiya, Zareena, and Parveena are losing touch with many of their traditions. These include their mother tongue Urdu or other sartorial, exquisite qualities of their etiquette their forefathers treasured dearly.

Unlike less prosperous fellow Muslims, they take to English and discuss Geoffrey Chaucer along with other British litterateurs. They also had the resources to pursue higher education in the west, eventually settle down there, and become the exalted entity that is the NRI (Non-Residential Indian).

Clearly, Chandni Begum is told predominantly from the lens of the more fortunate and educated segment of North Indian Muslims Nonetheless, it is an absorbing, relevant tale of a constantly evolving India, especially as the author’ home state Uttar Pradesh — her cherished abode of Ganga-Jamuna Tehzeeb — is more of a laboratory for communalism than it has ever been since 1947.