There was a time when historical discussions thrived in universities and intellectual circles. I vividly remember that during my college years in the early 1970s, there were passionate debates about where to begin the history of Pakistan. Should it start with the ancient civilisation of Harappa, or with the arrival of the first Muslim, Muhammad Bin Qasim, in 712? There were also discussions on whether Punjabi was an Aryan or pre-Aryan language. Additionally, the history of Punjab and its people was frequently debated. Seminars and debates among political intellectuals and in universities were common. Unfortunately, this is no longer the case. The imposition of martial law under military dictator Zia-ul-Haq in 1977 marked the end of such discussions.

The teaching of social sciences was discouraged, with history and philosophy being singled out. Philosophy, in particular, was nearly abolished, but this move was met with resistance from academia and enlightened intellectuals. We all know that the official history propagated by the state has never resonated with the people. The mantra of "one nation, one religion, one language" has not succeeded. The powerful—whether real or hybrid—fear the people's history, which is largely a history of resistance and rebellion.

In these repressive times, the emergence of the Lyallpur Young Historians Club (LYHC) in 2019-2020 felt like a breath of fresh air, especially during the isolation of the COVID-19 pandemic. We eagerly awaited the online lectures conducted by LYHC, as they provided the only intellectual stimulation available at that time.

The driving force behind LYHC was two young professors, Dr Khola Iftikhar Cheema and Dr Tohid Ahmad Chatta, who led a team that revitalised Lyallpur’s cultural and literary scene. Once known as the Manchester of India, Lyallpur has now become a hub for literature, art, and history. There are already two major literary festivals in the city—the Lyallpur Literary Festival and the Lyallpur Sulekh Mela—and now another prominent event has been added: the "International Lyallpur History Conference 2024." This two-day conference was held on August 26-27, organised by the Lyallpur Literary Council (LLC) in collaboration with and implemented by LYHC. The LLC is led by its president, Mr. Musadaq Zulqarnain, while Dr Khola Cheema served as the conference convener.

In his welcome address on “The Importance of Regional History,” Musadaq Zulqarnain emphasised the need to focus on regional narratives within the broader global discourse. “Regions hold distinct cultural identities that need to be not only preserved but also celebrated,” he said. “By choosing Lyallpur as the conference venue, we not only acknowledge its historical importance but also foster local connections and promote regional studies, highlighting the city’s unique contribution to the broader historical narrative.”

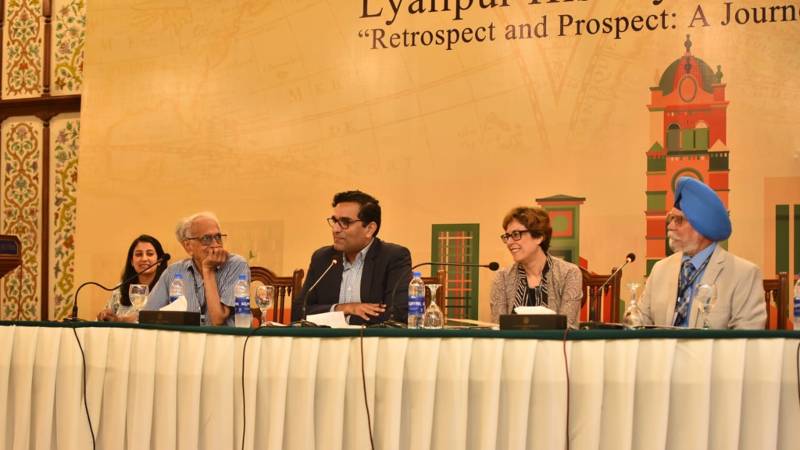

The conference was dedicated to the renowned historian Khursheed Kamal Aziz, who hailed from Lyallpur and authored numerous noteworthy books on Punjab, Pakistan and the Indian Subcontinent. Over the course of two days, the conference hosted a variety of sessions. The first plenary session, titled “Importance of Regional History,” had Dr Anne Murphy (UBC) as the keynote speaker and panel chair, with contributions from Mr. Musadaq Zulqarnain, Dr Ali Usman Qasmi (LUMS), Dr Philipp Zehmisch (Heidelberg), and Dr Anne Castaing.

The driving force behind LYHC was two young professors, Dr Khola Iftikhar Cheema and Dr Tohid Ahmad Chatta, who led a team that revitalised the cultural and literary scene

Prof Anne Murphy’s keynote talk explored Joshua Fazl-ud-Din in the context of regional history, focusing on Lyallpur, while also placing him within broader historical frameworks. Her presentation highlighted the various levels of analysis—from local and regional to global—that are essential for understanding the history of Lyallpur/Faisalabad. Murphy's paper examined the magazine Punjabi Darbar, founded by Joshua Fazl-ud-Din in Lyallpur in 1928, and reflected on its expansive and inclusive vision, which was deeply rooted in the Punjabi language (bolli).

Another noteworthy session was titled “Struggles and Perspectives in Colonial Punjab: Revolutionary Voices, Labor Movements, and Communal Identities of Lyallpur.” This panel was chaired by Prof Muhammad Iqbal Chawla (PU) and included presentations from independent researcher Aamir Riaz and Prof Pashaura Singh. Aamir Riaz's paper stood out as it was not laden with academic jargon, making it particularly relevant to the history of Lyallpur and Punjab. His topic, “Anti-Colonial Struggle in the Subcontinent: What Went Wrong?” elaborated on the various forms of resistance to colonialism. He pointed out that, unlike many other societies, the subcontinent resisted colonial rule in multiple ways. However, 77 years after independence, religious extremists and narrow nationalists persist across both sides of the border. He argued that it’s crucial to reassess what went wrong. The “religion card” and an exclusive form of nationalism were not only tools of the colonial masters but were also used during the anti-colonial struggle itself. The Movement for United Bengal was the first mass movement where religion (Hindu) and nationalism (Bengali) were extensively intertwined, and the consequences of this can still be felt today. Even after August 1947, nationalism and religious divisions continued to influence statecraft and various movements in both India and Pakistan, contributing to ongoing issues.

Dr Pashaura Singh, a professor from the University of California, presented his paper on “The 1907 Agrarian Revolt (Pagri Sambhal Jatta) of Lyallpur in Relation to the Present Kissan Movement in India.” He emphasised the leading role played by Sikh leader Ajit Singh in the farmers’ movement during British rule, asserting that these movements not only empowered farmers but also laid the groundwork for the independence struggle in the subcontinent. Linking this historic revolt to contemporary farmers’ protests in Indian Punjab, Singh remarked that the tradition of resistance and rebellion continues.

Dr Pippa Virdee from De Montfort University, UK, delivered a comparative study of Lyallpur and Ludhiana, revealing historical parallels between the two cities. “Before the Partition, Ludhiana and Lyallpur were modest towns, partially connected through the canal colonies,” she explained. Her research examined the impact of mass migrations and the loss of ancestral homelands.

Dr Philipp Zehmisch from the University of Heidelberg, Germany, presented a paper titled “On the Relationship Between Historiography and Ethnography.” Using Bhagat Singh, a native of Lyallpur who was executed by the British Raj at the age of 23, as a case study, Zehmisch discussed the themes of memory and erasure. “Bhagat Singh is celebrated as an anti-colonial freedom fighter in India, but his legacy has been largely forgotten in the official narratives of Pakistan’s freedom struggle,” he noted. “We need to reflect on how Bhagat Singh’s legacy can be understood and address the marginalisation of his contributions.”

Another fascinating session, titled “The Methodological Diversity to Understand Regional History,” was chaired by Prof Pashaura Singh (University of California) and featured Dr Yaqoob Bangash, Prof Pippa Virdee, Prof Pervaiz Vandal (NCA), and Dr Pierre Alain Baud. Pervaiz Vandal, a renowned architect, focused on Punjab’s architecture, emphasising its unique characteristics. He argued that architecture should be classified based on the region it emerges from, shaped by local culture, materials, and technology. During the colonial era, architecture was often categorised by religion, but Vandal urged that we move away from this colonial mindset. He stressed that the architecture of a nation doesn’t need to adhere to a single style; instead, it should be seen as a vibrant bouquet that reflects the diversity of its people. Punjab’s architecture is particularly known for its mastery of brickwork. The intense sunlight creates deep shadows that enhance surface decoration, while lightweight furniture is designed for mobility, such as the daily tradition of moving the manji (traditional bed) between the rooftop and the ground floor. Unlike royal architecture, Punjab’s vernacular buildings are pedestrian-friendly and reflect the everyday lives of its people.

The conference concluded on a high note, marking a rare and successful gathering of both local and international scholars. It is worth noting that a private organisation accomplished what universities and research institutes should have been doing. It would have been beneficial to include sessions in Punjabi or even in Urdu. For instance, it would have been valuable if Irfan Valara, a researcher from Quaid-i-Azam University, had been allowed to present his paper on the work and lifestyle of khojis (trackers) in Punjab villages—in Punjabi. Publishing the conference papers in book form would also add lasting value to this significant event.