In Pedagogy of the Oppressed (1968), Paulo Freire, a Brazilian educator and Marxist philosopher, critiques the banking model of education in which the teacher assumes omniscience and the student passively receive ‘facts’ and ideas (read: propaganda), without the freedom to question either the teacher and the world around her. The parallels between Freire’s arguments and the contemporary Pakistan are striking, suggesting an acute resonance between the text and the country’s socio-political landscape.

This country of 250 million people embodies the classic example of the oppressor and the oppressed. The oppressor, often identified as the hybrid elite, plunders the natural resources from the peripheries and loots the national kitty, while living in urban mansions with clean drinking water, uninterrupted energy, waste-free streets, and English-speaking children. Conversely, the oppressed comprising the majority of the population of women, men, and emaciated children, breathe toxic air, drink poisonous water, and live in low to high levels of poverty in crammed houses, capping it all with the high inflation and humiliation at the hands of petty Sarkari officials.

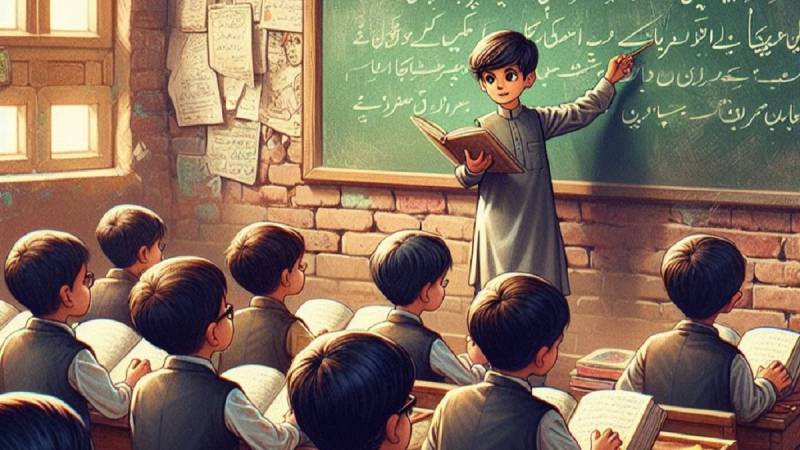

Paulo would have us believe that the perpetuation of this oppression hinges on the dehumanization of the large swathes of population, achieved through indoctrinating the millions of children with notions that attribute blame to the oppressed. It begins at school where the teacher denies the student avenues of self-expression and critical thought, the latter passively absorbing propaganda in the name of education. Later in life, the student cannot see her oppressors and often takes them for benefactors and sometimes blame herself for the predicament she is in. Consequently, these ideas are internalized by the oppressed, leaving little room for mass protests and civil resistance.

The other lethal weapon the oppressor uses is dividing the oppressed on issues that warrant a unified position: for instance, a large number of men in Pakistan believe that household chores and childcare is the sole responsibility of women, while ruthlessly criticizing Aurat March. These misogynistic attitudes are drilled into impressionable minds through religion and culture taught in education institutions, effectively diluting resistance that could bring about an end to the oppression.

Paulo Freire is certainly not the only education theorist advocating critical pedagogy to humanize the oppressed and awaken political consciousness, beginning in the classrooms. John Dewey and Bertrand Russell, two heavyweights in the progressive education cannon, also wrote extensively on critical pedagogy through which teachers and students become co-creator of new knowledge/ideas, empowering students to pursue their own interests, exercise their voice in the community, and fight against injustice and inequalities. In the 20th century, young people trained along these education principles participated in anti-war protests and civil rights movements, founded Green Peace and stood by feminists till women were victorious.

The subsequent decades in the Western world witnessed the rolling back of progressive education and critical pedagogy, under the misleading name of ‘education reform’ movement, crushing the rebellious spirit that gave a headache to the political and economic elites. No wonder that abortion rights have been reversed in the USA and genocide in Palestine met miffed opposition across the world.

The point is that social justice and democracy are not separate from the process of the teaching and learning, and must begin in classrooms, with the teacher and the student questioning the worldviews of the oppressor and coming up with alternative viewpoints. Paulo calls this problem-posing model of education, which encourages exchange of knowledge between teacher and student, blurring the traditional lines of instructor and learner. This leads to the humanization of the oppressed and make them aware of the subterfuges employed by the oppressors, significantly contributing to acute political consciousness and courage to fight injustice in the real world.

These education principles hold immense potential for Pakistan with around 64 percent of the population under the age of 30 and approximately 50 million children. The 2 million educators would only be worth their salt if they eschew authoritarian mores and promote free inquiry and dialogue in the classrooms. Students should not be frowned upon as inferiors and must have freedom to question and critique ideas prevalent in the society.

We cannot expect the oppressors to promote critical pedagogy among educators, but we can demand from educators to take up the gauntlet and produce a crop of young people who do not look away when elections are stolen and resources plundered, internet is shut down, religion is weaponized, and violence against women is perpetrated.

Embracing pedagogy of the oppressed could catalyze the liberation of Pakistan’s 230 million inhabitants, provided it begins in the classrooms now.