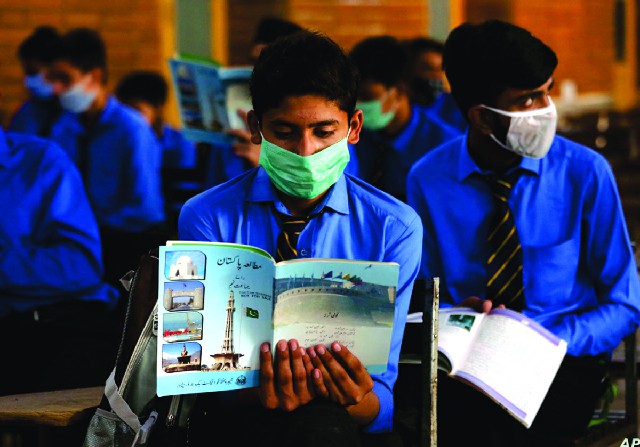

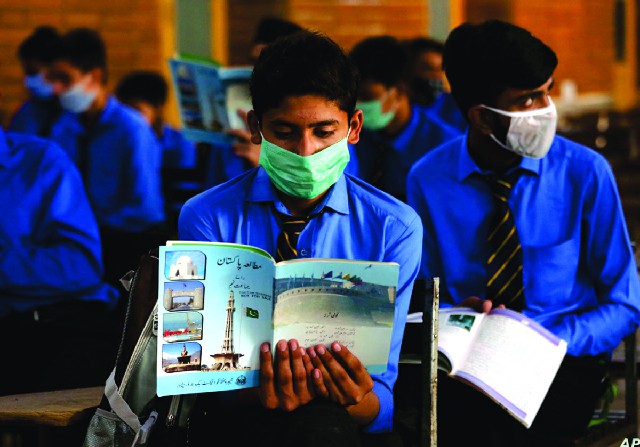

The Coronavirus has, among other things, hit our educational system very badly. Ever since the emergence of Covid-19, the educational system that was already in a shambles, has suffered a lot. Educational institutions have been closed down at various times in order to avoid the havoc that Covid has been wreaking on the countries it has gripped. Thus, it is imperative to have a look at the sorry state of education in Pakistan and analyse it to find out what has gone wrong.

Despite the fact that education is indispensable for social development, increased political awareness and a robust economy, it seems that our educational decline continues without an end in sight. The number of children out of school in the age group 5-16, according to UNICEF, remains second highest in the world – standing at 22.8 million, which represents 44 percent of the population in that age group. Moreover, the dropout rate for Pakistan remains one of the highest as compared to that of the other developing countries. For instance, according to a report of the Finance Division of Pakistan, the average dropout rates in primary education from 2007 to 2016 for Pakistan, India and Iran remained 22.7, 9.8 and 2.5 percent respectively. There is a marked gulf between the dropout rates for Iran and India when compared to those of Pakistan. Such pieces of data do nothing but reveal the sorry state of our education.

As has been said earlier, education plays a pivotal role in nation-building. Countries that regulate the world order have reached this position due to advancement in their education, science and technology. Japan and China have made rapid progress within the last century. After World War II, Japan had been almost destroyed; its economy was devastated due to its defeat at the hands of the Allied powers. More than any thing else, two of Japan’s biggest cities were attacked with atomic bombs. However, just 75 years after the end of war, Japan is again one of the developed counties and ranks at the 24th position on the Human Development Index, with a literacy rate of about 99 per cent. As regards China, it was faced with more than a normal share of developmental problems. China was overburdened with its gigantic population. It was not in a position to even feed its entire population. Both China and Japan have undergone rapid development and economic growth. So what exactly accounts for their such breathtaking progress? There can be other reasons in terms of economic policies and accountability mechanisms. However, the most apparent reason seems to be their emphasis on education. During their transformational period of development, education remained at the forefront of their policymakers’ minds. The developmental results of this approach are clear for all to see.

Numerous factors are responsible for the downfall of our educational system here in Pakistan. These include poverty, poor infrastructure, unskilled teachers, improper supervision, low budget, poor policies, political intervention, an uninspiring environment in school, a lack of cocurricular activities and so on. These are all major factors that have contributed to our collapsed education. Of all these, poverty and poor infrastructure are two main factors that have negatively impacted education. Children belonging to poor families start going to school late. Or even in some cases they never go to classrooms at all. As per UNICEF, “in the 5-9 age group, 5 million children are not enrolled.” Those who attend school drop out too soon in order to go to work so that they can contribute to their meagre family income. According to a report by the World Bank and projections of the IMF, poverty in Pakistan has risen from 24.3 percent in 2015 to about 40 percent in 2021. This paints a grim picture when it comes to the educational attainment of children. The number of children belonging to poor families is staggering: 36 percent of total population, because Pakistan has 80 million children out of a total population of 220 million.

According to a report by UNICEF, about 3.3 million children are trapped in child labour which, among other things, deprives them of education. Education is a basic right guaranteed by the article 25-A of the Constitution of Pakistan, which says that the state would provide free and compulsory education to children in 5-16 age group.

In addition to poverty, poor infrastructure also hampers access to education. A report from a survey conducted independently in 2016 stated that about 48% of schools lack toilets. Besides this, a number of schools lack basic necessities such as access to drinking water and electricity. As revealed by a report from the Reform and Support of the Sindh Education and Literacy Department, in Sindh alone, out of 49,130 schools, some 30,000 run without electricity; meanwhile 26,260 lack a facility for drinking water.

The list of the causes for the decline in our education will go on endlessly. Without going into the details of the other contributing factors, let us have a look at the things that can be done for the betterment of it.

After a careful analysis, one would conclude that the availability of money is not sole factor responsible for this horrific situation, for education is now a provincial subject after the 18th constitutional amendment. Provinces are free to allocate as much of their funds as they want. However, the issues that plague the system are deeply ingrained in our governance system. Largely, bad governance and mismanagement on the part of authorities have resulted in this situation. For example, the funds issued for the repair and renovation of schools are misappropriated; teachers evade delivering their duty without fear of supervision.

Bad governance is the mother of all kinds of corruption. It stems from political instability, political interference in the affairs of other departments, lack of accountability and transparency, poor policies and so on.

Unless this bad governance is tackled effectively, there will be no improvement in our educational system. Addressing the problem needs a broad approach – one that emphasizes actual implementation just as much as policymaking itself.

Despite the fact that education is indispensable for social development, increased political awareness and a robust economy, it seems that our educational decline continues without an end in sight. The number of children out of school in the age group 5-16, according to UNICEF, remains second highest in the world – standing at 22.8 million, which represents 44 percent of the population in that age group. Moreover, the dropout rate for Pakistan remains one of the highest as compared to that of the other developing countries. For instance, according to a report of the Finance Division of Pakistan, the average dropout rates in primary education from 2007 to 2016 for Pakistan, India and Iran remained 22.7, 9.8 and 2.5 percent respectively. There is a marked gulf between the dropout rates for Iran and India when compared to those of Pakistan. Such pieces of data do nothing but reveal the sorry state of our education.

The number of children out of school in the age group 5-16, according to UNICEF, remains second highest in the world – standing at 22.8 million, which represents 44 percent of the population in that age group

As has been said earlier, education plays a pivotal role in nation-building. Countries that regulate the world order have reached this position due to advancement in their education, science and technology. Japan and China have made rapid progress within the last century. After World War II, Japan had been almost destroyed; its economy was devastated due to its defeat at the hands of the Allied powers. More than any thing else, two of Japan’s biggest cities were attacked with atomic bombs. However, just 75 years after the end of war, Japan is again one of the developed counties and ranks at the 24th position on the Human Development Index, with a literacy rate of about 99 per cent. As regards China, it was faced with more than a normal share of developmental problems. China was overburdened with its gigantic population. It was not in a position to even feed its entire population. Both China and Japan have undergone rapid development and economic growth. So what exactly accounts for their such breathtaking progress? There can be other reasons in terms of economic policies and accountability mechanisms. However, the most apparent reason seems to be their emphasis on education. During their transformational period of development, education remained at the forefront of their policymakers’ minds. The developmental results of this approach are clear for all to see.

Numerous factors are responsible for the downfall of our educational system here in Pakistan. These include poverty, poor infrastructure, unskilled teachers, improper supervision, low budget, poor policies, political intervention, an uninspiring environment in school, a lack of cocurricular activities and so on. These are all major factors that have contributed to our collapsed education. Of all these, poverty and poor infrastructure are two main factors that have negatively impacted education. Children belonging to poor families start going to school late. Or even in some cases they never go to classrooms at all. As per UNICEF, “in the 5-9 age group, 5 million children are not enrolled.” Those who attend school drop out too soon in order to go to work so that they can contribute to their meagre family income. According to a report by the World Bank and projections of the IMF, poverty in Pakistan has risen from 24.3 percent in 2015 to about 40 percent in 2021. This paints a grim picture when it comes to the educational attainment of children. The number of children belonging to poor families is staggering: 36 percent of total population, because Pakistan has 80 million children out of a total population of 220 million.

After a careful analysis, one would conclude that the availability of money is not sole factor responsible for this horrific situation, for education is now a provincial subject after the 18th constitutional amendment

According to a report by UNICEF, about 3.3 million children are trapped in child labour which, among other things, deprives them of education. Education is a basic right guaranteed by the article 25-A of the Constitution of Pakistan, which says that the state would provide free and compulsory education to children in 5-16 age group.

In addition to poverty, poor infrastructure also hampers access to education. A report from a survey conducted independently in 2016 stated that about 48% of schools lack toilets. Besides this, a number of schools lack basic necessities such as access to drinking water and electricity. As revealed by a report from the Reform and Support of the Sindh Education and Literacy Department, in Sindh alone, out of 49,130 schools, some 30,000 run without electricity; meanwhile 26,260 lack a facility for drinking water.

The list of the causes for the decline in our education will go on endlessly. Without going into the details of the other contributing factors, let us have a look at the things that can be done for the betterment of it.

After a careful analysis, one would conclude that the availability of money is not sole factor responsible for this horrific situation, for education is now a provincial subject after the 18th constitutional amendment. Provinces are free to allocate as much of their funds as they want. However, the issues that plague the system are deeply ingrained in our governance system. Largely, bad governance and mismanagement on the part of authorities have resulted in this situation. For example, the funds issued for the repair and renovation of schools are misappropriated; teachers evade delivering their duty without fear of supervision.

Bad governance is the mother of all kinds of corruption. It stems from political instability, political interference in the affairs of other departments, lack of accountability and transparency, poor policies and so on.

Unless this bad governance is tackled effectively, there will be no improvement in our educational system. Addressing the problem needs a broad approach – one that emphasizes actual implementation just as much as policymaking itself.