Tahir Yazdani Malik is the founder of Lahore Heritage Club (LHC), a self-financed organization working for the conservation, preservation, and management of the rich cultural heritage of Lahore and Pakistan.

As a student he worked at the Pakistan Medical Research Center where many foreigners worked in the lab alongside him. At the end of their stay they would want to shop for local crafts, especially carpets (every foreigner wants a carpet), so he would escort them. In the process of showing them around, Mr. Yazdani became passionate about our values, heritage and history.

Q. How long has LHC been around?

In 1990 I opened LHC in a flat I owned in Liberty Market. I ran it as a guest house called ‘Dum Mala Dosh’, an Uzbek phrase for ‘Guest house for Young people’. Students rented rooms there on a temporary basis.

With the rent I collected, I bought artifacts for the club. Further, the renters supported the club by donating old locks, keys and lanterns. One student even gave me his grandfather’s Parker pen.

In 2007 I closed LHC in Liberty because it was on the 4th floor and hardly anybody visited it, deciding to move it, instead, to my own home.

Q. Tell me about your journey in founding the Lahore Heritage Club.

I am fascinated by architecture and that led to my curiosity about bricks, which I started to collect. There were rich and diverse brick-making techniques in the Indus Valley Basin civilizations: Moenjodaro, Harrapa, Uch, Multan. Uch and Multani brick craft came from Central Asia, Iran and Turkey: a region that has a lot of firozas and lapis lazuli – the two gemstones that were used as enamels. Terracotta bricks were also enameled and baked, which is how tile-making started. For over 600 years these tiles resisted moisture and decay, thanks to the process of enameled metallic coating. These bricks were used on the façade of homes in the walled city. The top balcony was always partially tiled using small bricks that fit together in patterns of birds and flowers. You could not see through the designed openings and yet it allowed air flow. It also added privacy. When you were right at the top of the building, in winter to sun bathe, and in the summer to sleep on rooftops, you didn’t want your next door neighbor peeping in. Walled city culture was that you put your charpai (bed) at the level of your banera (balcony) and your neighborly ethics demanded you would not look over the banera into others’ courtyard.

Q. So you started with bricks. And then?

Little by little the whole building became my fascination. Items from buildings were thrown away when houses got demolished. I collected wooden structures, jharokas with ornate latticework and shateeris (central rafter in roof). The central rafter always sported an elegant hand-painted motif. The design was unique for each family.

In the 1980 and 90s, walled city dwellers moved to Gulberg, Defence, or Model Town to better their daughters’ marriage prospects. Their daughters, though graduating from Kinnaird, Home Economics, or NCA, were passed over when prospectors learnt that the family lived in Gawalmandi, Bhaati, or Lohari. A home in Gulberg, Defence or Model Town was a status symbol. That was when rampant deterioration started. Buyers demolished residences to build plazas and rapid commercialization took place.

Q. Bricks, doors, ceilings, what next?

In old city, the well-to-do had many collectible items for heritage lovers: gramophones, radios, lanterns, dowry dishes, copper hamams, mattees etc.

Mattee (grain storage containers), forged from different metals, were quite ornamental. Hamams, used for heating water in winter were functional and economical, needing very few coals to heat water. Mattees are no more, neither are hamams.

Each home had an array of pots from small to large that were kept clean and shining. It was important to have every size: pots to cook for one or two people or for fifty. The pots had level markings: how much water to put for one kilo rice, how much for two. Today, you follow recipes and still can go wrong. In those days when guests came unexpectedly, pots with markers were handy.

Q: How about plates and glasses?

There was no concept of plates: plates is a Western concept. Folks ate food in piyalas (bowls). Every family had a lot of metal piyalas that were constantly washed and used. The piyala was totally versatile: people ate food and dessert and drank milk or water from them. Unfortunately, we have finished the piyala.

In Kansi (bell metal) glasses, lassi stayed cool while food remained hot. This is because kansi absorbs temperature. Well-to-do families used kansi utensils, middle class families had taanba (copper) dishes.

Families who owned crockery and cutlery sets only used them when visited by distinguished guests.

A mardana baithak (men’s drawing room) and a tharra (raised outdoor platform) were used to entertain and socialize. (There was no drawing room, dining room concept.)

Q. What about decoration pieces?

In average homes, piyalas and glasses was placed in a cornice in the wall and this was a decoration; delicately embroidered hankies were put on display. Prosperous households displayed crockery, cutlery and dinner sets in a glass paneled cabinet (Western items).

Q. All your collection is from the walled city?

My poster collection comes from Bombay Music House in Old Anarkali. When the owner died his son sold the place. One day I walked into the shop and found gutter water was flowing inside and dripping on the posters on the walls from the upper storey.

I made a deal with the son and gave him token money for all his 18 posters which showcased pre-partition music icons: Kausar Parveen, Nazakat Ali, Salamat Ali, Noor Jehan, Geeta Roy, Malika Pukhraj, Madhu Bala, Geeta Bali, His Masters Voice, etc.

Before I could pick up my posters, Naeem Bokhari, Tahira Syed's husband, offered to buy Malika Pukhraj's poster for five times my bidding price

Before I could pick up my posters, Naeem Bokhari, Tahira Syed’s husband, offered to buy Malika Pukhraj’s poster for five times my bidding price. When I arrived the owner’s son sadly professed, “I promised you all the posters, but Naeem Bokhari insisted that he had to get the Malika Pukhraj poster for his wife and I ended up selling it to him.” So, I got 17 posters!

After posters, I turned to collecting films, records, music, old movies and projectors (35mm, 15mm, 8mm). My entire collection came from people who actually worked in those arts and in a way belonged to those arts.

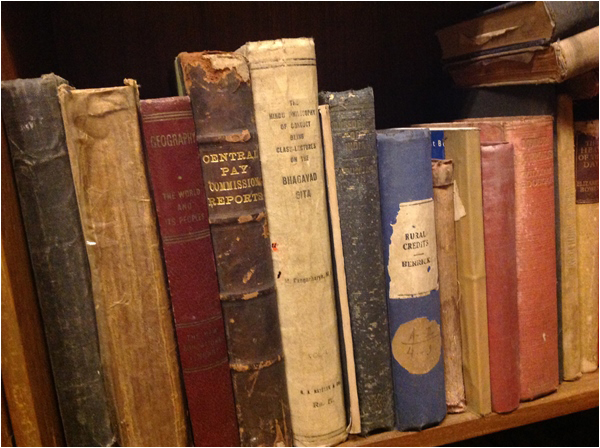

My book collection came from my family. I have Persian calligraphy, Qurans, books on Indian History, architecture, art and crafts, free masonry, and lots of old newspapers. When I founded LHC people would ask about newsworthy incidents and dates, etc. To respond to them I started collecting newspapers such as the Civil & Military Gazette, Nawai-Pakistan and other dailies.

Q. Tell me other acquisitions, any interesting story ….

In Anarkali, a dharmshala got occupied by a couple of families. One day when I went there one of the resident families were celebrating their daughter’s wedding. They had taken off the main door of the temple, made a fire from it and were cooking a Korma Deg on it. It was a huge, solid, 14 ft wooden door; big like the Bhaati Lahori doors and was embellished with elaborately carved floral bouquets.

I was horrified and asked the family not to burn down the whole thing, but they were obviously more concerned about their daughter’s wedding than my seemingly highbrow concerns. I told them I would go to pathan taal (place selling wood) and get wood for them to burn, pleading with them to slow down the process till I came back with some wood. I ran to the taal and rushed back, but they demanded more money, which I ended up paying. But the taal wood wouldn’t catch fire, and I stood there lamenting the loss of my money and heritage. Finally, the wood caught fire and they let me remove the door. One palla (panel) was burnt, I picked up the other palla and preserved it.

I was told Goga Shahi, a powerful Don in the walled city, could help me

Q. The average person needs to participate in the preservation of our heritage…

I will tell you an interesting incident. I bought a three marla house in the inner city, midpoint between Lohari and Bhaati, which the owner then also sold to someone else behind my back, refusing to give me back my money. I was told Goga Shahi, a powerful Don in the walled city, could help me. I went to see him. Several gunmen guarded his den. He sent his men after the debtor and procured my money immediately. A person like Goga has influence and can save more buildings than the government can.

Then there is a Dr. Sahib near Neeween Masjid. Dr. Sahib is often called to give first aid to gun shot wounds. He is greatly respected in the walled city. I complained to him that toxic non-food orange color was being mixed in jalebis. He forbade shopkeepers and now most shops in Lohari do not put colour in Jalebis.

We need to get the support of such people who are influential in the walled city. They are in a position to raise awareness and influence residents in favour of preservation.

Q. Do people approach you to sell your antiques?

They do. But when scavengers bring items from public places, such as mandirs (hindu temples) or graveyards, I refuse to buy them, though there are other collectors who do buy from them.

Q. Why do you refuse?

I believe such buying is not heritage preservation, rather it is heritage trading. Buying from religious sites and public places leads to vandalism. There is a line between vandalism and preservation. If you put a gravestone (even if it is 200 years old) in a food court or I put it in my gallery, it will lead to finishing of a public place, finishing off a graveyard. If you buy stolen goods, then people will bring you things from all over the country; this is from Moejodaro, this is from Uch – take this, take that. For example, if the dharmsala door had been in place, I would not have taken it. It was burning, that is why I took it. I saved it. If I had taken the door off its hinges and brought it home that would have been vandalism.

In the Lahore fort, a piece fell out from a priceless pictured wall. I could have picked it up and brought it home, instead I made a film on that piece. I took six students from the NCA multimedia department and right there before the students I put back the fallen piece from the Lahore fort wall. I inculcated in the students that if I take the piece, I will preserve it, but its rightful place is back on the wall from where it fell and that is how you contribute to the city and to world heritage sites.

Q. LHC is on the ground floor of your home. Does your wife grudge sharing half her home with old knick knacks?

She has a little bit of a grudge. She is not very fond of old things. When in great excitement I take an artifact upstairs to the kitchen pantry to wash it, she is annoyed. So, I have made a wash basin downstairs to avoid conflict. However, the club gets many visitors and she has begun acknowledging my work. She sees that the things she throws outside are things people get photos taken with. Her perception is changing and my children’s too.

A woman would embroider a handkerchief for years, to perfection, to give to her beloved. There was joy in these hankies

Q. What else is special in your collection?

I have Balochi crafts to which very few people have access in Punjab. I have a set of handmade dadree guns from Balochistan. Different materials were used to decorate and embellish them, copper, glass, ivory, mother-of-pearl. These embellishments are iconic symbols of family traditions and show how particular guns passed from one generation to the next.

Balochi hankerchiefs are priceless. A woman would embroider a roomal (handkerchief) for years, to perfection, to give to her beloved. There was joy in these hankies.

Male valour is expressed with Balochi guns. Feminine graces reveal themselves in Balochi handkerchiefs.

Q. What is your favorite part of your collection?

Everything is a favourite, I get emotionally attached but some I cherish even more than others. I prize my gold and mother-of-pearl calligraphy and hand written books that are four to five hundred years old. These books were handwritten, in Persian and Arabic, by people living in Lahore. They are sort of self-help diaries about how to live a life. Maybe a father wrote it for his children or brother for brother. Very unique!

Q. What is your vision for LHC?

To take it to a global audience and it is beginning to happen from my Facebook Fan Page where I get hits from the US, UK, Gulf States and India. The heritage of the Indus Valley Basin is our priceless asset that we can declare to the world.