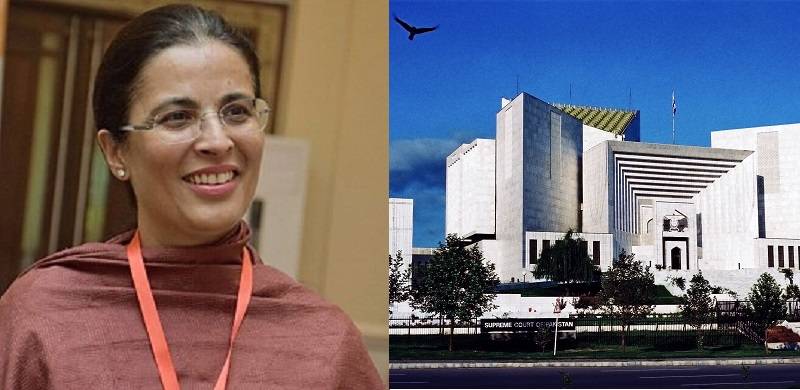

Once again Pakistan stands on the edge of making history by appointing Justice Ayesha Malik as the first female Supreme Court judge, and once again, there is vicious opposition to her appointment. This questionable yet not surprising opposition is led by the Pakistan Bar Council (PBC) along with several lawyers’ groups who have masked this controversial action under the garb of the ‘protection’ of ‘rule of law’. The PBC has opposed the appointment, arguing that seniority is a settled principle when appointing judges to the apex court and that judges senior to her should be appointed first, as she is fourth in the seniority list. They cite that this principle is enshrined within the Constitution of Pakistan 1973. They have also pointed out that Justice Ayesha Malik was earlier disapproved by the Judicial Commission. The PBC has announced street protests as well as a lawyers’ strike all over Pakistan on this issue.

Let us ignore, for a moment, how the sight of predominantly male lawyers of a predominantly male-run professional organisation protesting against the first appointment of a female judge to a male-dominated Supreme Court is perhaps the worst blot on the image of Pakistan’s claim that it prioritszes gender equality. As such, the very argument coming from the PBC is itself groundless.

First of all, the Honourable Justice was not “disapproved” by the commission. This is deliberate misinformation being spread by various groups. The commission was deadlocked and then adjourned – and to call that ‘disapproval’ is the height of a vitriolic attack on a very competent Justice whose performance is well recognized by judges and lawyers all over the country. Secondly, their statement that seniority is a constitutionally enshrined principle is also flawed, as nowhere within the Constitution of Pakistan is it mentioned that for the appointment of Judges of the High Court to the Supreme Court, seniority is to be the central principle. This has been forwarded as a flawed argument meant to confuse the people as well as the legal fraternity. Lastly, the PBC have argued that they are standing for the principles enshrined within Al-Jehad Trust vs Federation of Pakistan PLD 1996 SC 324 where the courts considered the question of judicial appointment. This is another misinformed statement, as nowhere does it say within the said judgment that seniority for appointment of Supreme Court judges is to be the lone principle. The Supreme Court clarified this point in its later judgment passed by the Five Judicial Bench in Supreme Court Bar President vs Federation of Pakistan PLD 2002 SC 939, where it held the following:

“In our considered, view, the scope of the principles of seniority and, legitimate expectancy enunciated in those cases is restricted to the appointment of Chief Justice of a High Court and the Chief Justice of Pakistan and these principles neither apply nor can be extended to the appointment of Judges of the Supreme Court […] We are clear to our mind that neither the principle of seniority is applicable as a mandatory rule for appointment of p Judges in the Supreme Court nor the said rule has attained the status of a convention.”

The Supreme Court within this judgment interpreted that the Al-Jehad trust judgment did not enshrine seniority as the sole or mandatory principle for the appointment of Supreme Court judges, and thus the ‘Custodians’ of the Al-Jehad Trust judgment need to reread the judgment and the subsequent judgment revisit their slogan whilst determining whether they are for the principles of Al-Jehad Trust Judgment or against those principles since their actions highlight more to the latter rather than the former.

Seniority as a sole principle is being touted as the shield against the interference of the executive, and a guarantee of judicial independence. However, the fact that only 4% of countries in the world appoint judges based on seniority reveals the truth behind this so-called shield againt interference. After all, countries with far better protections for judicial independence employ proper safeguards – which do not sacrifice merit to the seniority principle. Under the seniority principle, a judge simply has to stay in their position without removal and can be appointed as Chief Justice or Justice to the Supreme Court – without having to give any meritorious performance or advancing legal understanding in the country. By making seniority the sole principle, we have successfully sacrificed merit and through it the incentive that excellence will be rewarded.

The UN Basic Principles on the Independence of the Judiciary states that the promotion of judges “should be based on objective factors in particularly ability, integrity and experience.” This is important to understand because the UN itself has highlighted that if integrity and ability are not considered for judicial appointments, then judicial independence is adversely impacted. The entire process of actually creating the judicial commission is to look at the aforementioned objective factors for the appointment of Supreme Court judges rather than rubber-stamping the senior-most judge. A similar viewpoint was seen being taken by the Council of Europe’s Commission for Democracy through Law (The Venice Commission), which highlighted that merit has to be the primary criterion and expanding on this they stated that Judicial diversity is an important aspect when considering judicial independence as the populace has more faith within the judiciary that is diversified through representation from otherwise unrepresented groups.

Judicial independence can only be protected when merit is made supreme. Seniority is no shield in this regard but a double-edged sword that may fight against the attacks of the executive but will endanger the evolution of the law within the state.

Ironically, Justice Ayesha Malik will not be the first non-senior appointment to the bench of the Supreme Court. In fact, since the inception of the country, 41 judges have been elevated bypassing seniormost judges, half of whom have been appointed since 1995. Even the current Supreme Court bench includes five such judges who bypassed seniority. This suggests that there is no real convention of seniority when appointing judges of the Supreme Court – even here in Pakistan where it is being touted against Justice Ayesha Malik.

Considering the above discussion, one is left to wonder as to why this scale of opposition and threats of protest for this particular appointment. What is so special this time, when it was absent for the last 41 times when seniority was bypassed? Perhaps the answer lies in opportunity and merit after all in a meritorious society, performance will decide appointment rather than seniority and that may close the doors for many and opportunity will knock on the doors of only the capable rather than on those who have survived long enough.

The legal profession demands its professionals to seek out the truth and advance the evolution of law within society. The lawyers of Pakistan need to ask themselves whether they stand for the advancement and protection of legal thought or are they simply around for the securing of the vested interests of a select few who profit from a broken system.

Let us ignore, for a moment, how the sight of predominantly male lawyers of a predominantly male-run professional organisation protesting against the first appointment of a female judge to a male-dominated Supreme Court is perhaps the worst blot on the image of Pakistan’s claim that it prioritszes gender equality. As such, the very argument coming from the PBC is itself groundless.

First of all, the Honourable Justice was not “disapproved” by the commission. This is deliberate misinformation being spread by various groups. The commission was deadlocked and then adjourned – and to call that ‘disapproval’ is the height of a vitriolic attack on a very competent Justice whose performance is well recognized by judges and lawyers all over the country. Secondly, their statement that seniority is a constitutionally enshrined principle is also flawed, as nowhere within the Constitution of Pakistan is it mentioned that for the appointment of Judges of the High Court to the Supreme Court, seniority is to be the central principle. This has been forwarded as a flawed argument meant to confuse the people as well as the legal fraternity. Lastly, the PBC have argued that they are standing for the principles enshrined within Al-Jehad Trust vs Federation of Pakistan PLD 1996 SC 324 where the courts considered the question of judicial appointment. This is another misinformed statement, as nowhere does it say within the said judgment that seniority for appointment of Supreme Court judges is to be the lone principle. The Supreme Court clarified this point in its later judgment passed by the Five Judicial Bench in Supreme Court Bar President vs Federation of Pakistan PLD 2002 SC 939, where it held the following:

“In our considered, view, the scope of the principles of seniority and, legitimate expectancy enunciated in those cases is restricted to the appointment of Chief Justice of a High Court and the Chief Justice of Pakistan and these principles neither apply nor can be extended to the appointment of Judges of the Supreme Court […] We are clear to our mind that neither the principle of seniority is applicable as a mandatory rule for appointment of p Judges in the Supreme Court nor the said rule has attained the status of a convention.”

The Supreme Court within this judgment interpreted that the Al-Jehad trust judgment did not enshrine seniority as the sole or mandatory principle for the appointment of Supreme Court judges, and thus the ‘Custodians’ of the Al-Jehad Trust judgment need to reread the judgment and the subsequent judgment revisit their slogan whilst determining whether they are for the principles of Al-Jehad Trust Judgment or against those principles since their actions highlight more to the latter rather than the former.

The fact that only 4% of countries in the world appoint judges based on seniority reveals the truth behind this so-called shield againt interference. After all, countries with far better protections for judicial independence employ proper safeguards – which do not sacrifice merit to the seniority principle

Seniority as a sole principle is being touted as the shield against the interference of the executive, and a guarantee of judicial independence. However, the fact that only 4% of countries in the world appoint judges based on seniority reveals the truth behind this so-called shield againt interference. After all, countries with far better protections for judicial independence employ proper safeguards – which do not sacrifice merit to the seniority principle. Under the seniority principle, a judge simply has to stay in their position without removal and can be appointed as Chief Justice or Justice to the Supreme Court – without having to give any meritorious performance or advancing legal understanding in the country. By making seniority the sole principle, we have successfully sacrificed merit and through it the incentive that excellence will be rewarded.

The UN Basic Principles on the Independence of the Judiciary states that the promotion of judges “should be based on objective factors in particularly ability, integrity and experience.” This is important to understand because the UN itself has highlighted that if integrity and ability are not considered for judicial appointments, then judicial independence is adversely impacted. The entire process of actually creating the judicial commission is to look at the aforementioned objective factors for the appointment of Supreme Court judges rather than rubber-stamping the senior-most judge. A similar viewpoint was seen being taken by the Council of Europe’s Commission for Democracy through Law (The Venice Commission), which highlighted that merit has to be the primary criterion and expanding on this they stated that Judicial diversity is an important aspect when considering judicial independence as the populace has more faith within the judiciary that is diversified through representation from otherwise unrepresented groups.

Judicial independence can only be protected when merit is made supreme. Seniority is no shield in this regard but a double-edged sword that may fight against the attacks of the executive but will endanger the evolution of the law within the state.

Ironically, Justice Ayesha Malik will not be the first non-senior appointment to the bench of the Supreme Court. In fact, since the inception of the country, 41 judges have been elevated bypassing seniormost judges, half of whom have been appointed since 1995. Even the current Supreme Court bench includes five such judges who bypassed seniority. This suggests that there is no real convention of seniority when appointing judges of the Supreme Court – even here in Pakistan where it is being touted against Justice Ayesha Malik.

Considering the above discussion, one is left to wonder as to why this scale of opposition and threats of protest for this particular appointment. What is so special this time, when it was absent for the last 41 times when seniority was bypassed? Perhaps the answer lies in opportunity and merit after all in a meritorious society, performance will decide appointment rather than seniority and that may close the doors for many and opportunity will knock on the doors of only the capable rather than on those who have survived long enough.

The legal profession demands its professionals to seek out the truth and advance the evolution of law within society. The lawyers of Pakistan need to ask themselves whether they stand for the advancement and protection of legal thought or are they simply around for the securing of the vested interests of a select few who profit from a broken system.