Last month, I attended an interesting series of trainings on ‘Diversity, Equity and Inclusion.’ My initial reaction was skeptical, but I found the purpose and thoughtfulness with which this program was conceived to be fascinating. I considered myself knowledgeable about the topic, but I soon realised my naivete in understanding the complexity of this discourse.

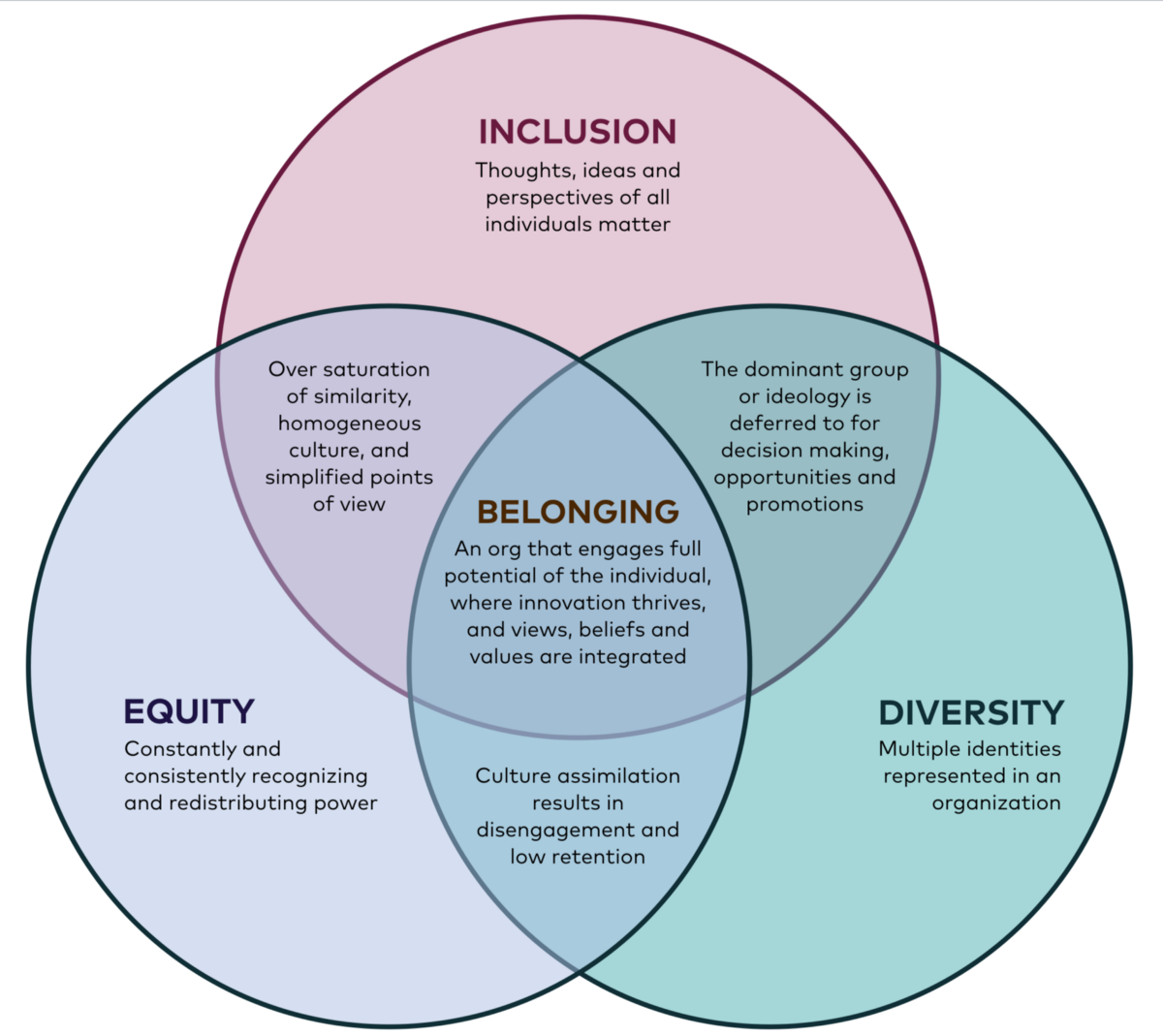

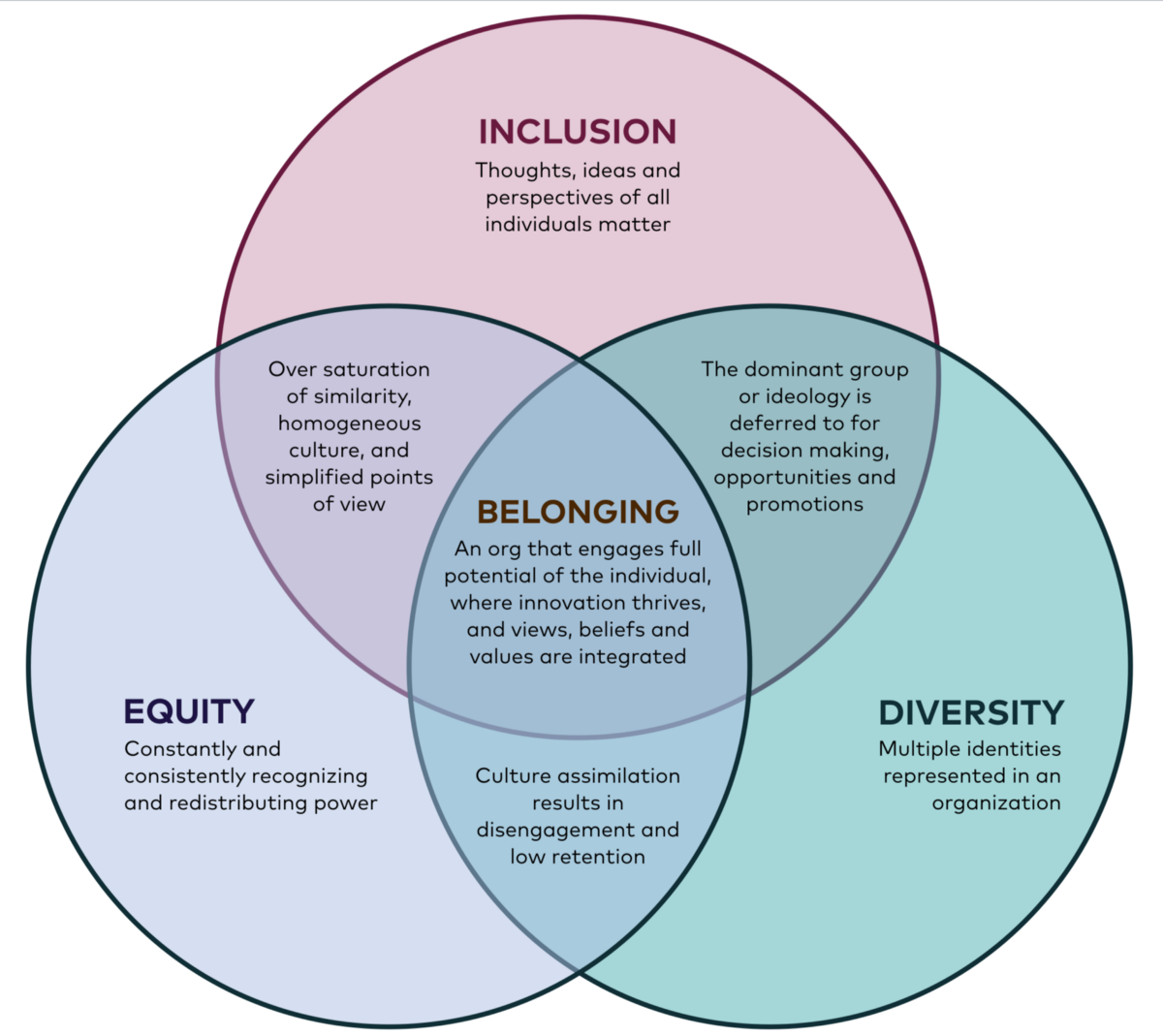

It is clear that the three concepts are interlinked. Diversity can have many aspects to it. Race and gender are the obvious ones that come to mind. It can also be broadened to include age, religion, life experience and socio-economic background.

Inclusion is linked to thoughts, ideas and perspectives. Each brings a diversity of opinions and thoughts that people need to have heard or seen. For anyone who has been excluded – whether from a group or school friends or at work – such exclusion can be painful. You know when you are included or not. It is even worse when it is intentional.

Equity is the absent link, which means that one is constantly in pivot. One can consistently recognize and redistribute power. For an organization, it ties into a sense of belonging. In any organization where innovation thrives and where views, values and belief systems can be integrated, members will be more willing to stay within longer. It also means a diverse environment means more for personal development. By being more accepting and more aware of other cultures and thoughts, one avoids group think.

Equity is the absent link, which means that one is constantly in pivot. One can consistently recognize and redistribute power. For an organization, it ties into a sense of belonging. In any organization where innovation thrives and where views, values and belief systems can be integrated, members will be more willing to stay within longer. It also means a diverse environment means more for personal development. By being more accepting and more aware of other cultures and thoughts, one avoids group think.

So how does this link to development or societal structures? Theoretically, we can agree that people, regardless of where they are from should be allowed full and equal access to basic economic freedom, education, health, social equality and benefit from policy settings.

What does that mean in reality? It means that no person should be denied entry to the loss of revenue and economic marginalisation. In societal terms, if you exclude people then you lose monetary value.

Mary Virginia Lee Badgett, a Professor of Economics at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, studied aspects of the exclusion of the LGBT community. They have all too often been at the receiving end of discrimination, even declared illegal by many countries. Her research revealed that the human cost of excluding LGBT from economies could be up to 1% of GDP, which should be an eye-opening fact for economists and policy makers.

That kind of decline could mean a recession and policy correction, but if one does not include the invisible cost of LGBT then it does not matter for what is not seen is not paid attention to. Her survey covers countries such as Canada, UK, Australia, India and the Philippines. Its results show that there are measurable and economic costs to bigotry and outlawing groups from societies. Its repercussions go far beyond just condemning these groups and excluding them from the social and economic fabric of a country.

Essentially, the conversation about diversity and inclusion is a conversation about rewriting internal bias. One needs to be mindful of one’s own inherent subconscious bias and actively root it out. Difference does not mean inferior.

These are radical thoughts indeed for most societies which are rooted in societal, class and economic structures. The UN officially recognises over thirty different characteristics of diversity. Some are obvious and can be seen, like race. Others are harder to detect, like nationalities or religion. Some are acquired over time, through education, socio-economic background or religious beliefs.

Over time, our perspectives also change – in our relationships, through marriage, having children, being exposed to discrimination. Many life experiences can alter how one thinks of diversity.

It is limiting to think only of race and gender when it comes to diversity, as it really refers to being able to bring different perspectives. In an organisation which has only engineers or only men or only one dominant ethnic group, anyone who doesn't belong to that group would likely feel excluded.

The inherent danger is that it leads in any profession to group-think. It is a known fact that the larger and more similar a group, the less likely individuals are to dissent. Groups can form norms and behaviors quickly and can develop blind spots quickly.

And nowhere is this clearer than minority protection, race or LGBTQ issues. Building an environment which is safe, whether in a family, organisation or society, means to build an environment in which people feel safe and valued as they are and feel – not how you pretend you would like them to be.

Symbolism matters in terms of equality - such as equal access to employment, housing or even social norms. I remember the outrage that Muslims felt as a result of 9/11. Many complained of being mistreated at immigration or visas, without being aware that they often practiced discrimination themselves.

We as a society have much to search within when it comes to these issues. The latest analytical thinking on this debate provides us the tools to confront such uncomfortable issues. Blatant persecution and discrimination can never be the answer – what may help us is to shift the paradigm to listen and have empathy. And above all, to recognise that diversity does not mean inferiority, and societies did not develop by practicing separatism.

It is clear that the three concepts are interlinked. Diversity can have many aspects to it. Race and gender are the obvious ones that come to mind. It can also be broadened to include age, religion, life experience and socio-economic background.

Inclusion is linked to thoughts, ideas and perspectives. Each brings a diversity of opinions and thoughts that people need to have heard or seen. For anyone who has been excluded – whether from a group or school friends or at work – such exclusion can be painful. You know when you are included or not. It is even worse when it is intentional.

Equity is the absent link, which means that one is constantly in pivot. One can consistently recognize and redistribute power. For an organization, it ties into a sense of belonging. In any organization where innovation thrives and where views, values and belief systems can be integrated, members will be more willing to stay within longer. It also means a diverse environment means more for personal development. By being more accepting and more aware of other cultures and thoughts, one avoids group think.

Equity is the absent link, which means that one is constantly in pivot. One can consistently recognize and redistribute power. For an organization, it ties into a sense of belonging. In any organization where innovation thrives and where views, values and belief systems can be integrated, members will be more willing to stay within longer. It also means a diverse environment means more for personal development. By being more accepting and more aware of other cultures and thoughts, one avoids group think.So how does this link to development or societal structures? Theoretically, we can agree that people, regardless of where they are from should be allowed full and equal access to basic economic freedom, education, health, social equality and benefit from policy settings.

What does that mean in reality? It means that no person should be denied entry to the loss of revenue and economic marginalisation. In societal terms, if you exclude people then you lose monetary value.

Mary Virginia Lee Badgett, a Professor of Economics at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, studied aspects of the exclusion of the LGBT community. They have all too often been at the receiving end of discrimination, even declared illegal by many countries. Her research revealed that the human cost of excluding LGBT from economies could be up to 1% of GDP, which should be an eye-opening fact for economists and policy makers.

That kind of decline could mean a recession and policy correction, but if one does not include the invisible cost of LGBT then it does not matter for what is not seen is not paid attention to. Her survey covers countries such as Canada, UK, Australia, India and the Philippines. Its results show that there are measurable and economic costs to bigotry and outlawing groups from societies. Its repercussions go far beyond just condemning these groups and excluding them from the social and economic fabric of a country.

Essentially, the conversation about diversity and inclusion is a conversation about rewriting internal bias. One needs to be mindful of one’s own inherent subconscious bias and actively root it out. Difference does not mean inferior.

These are radical thoughts indeed for most societies which are rooted in societal, class and economic structures. The UN officially recognises over thirty different characteristics of diversity. Some are obvious and can be seen, like race. Others are harder to detect, like nationalities or religion. Some are acquired over time, through education, socio-economic background or religious beliefs.

Over time, our perspectives also change – in our relationships, through marriage, having children, being exposed to discrimination. Many life experiences can alter how one thinks of diversity.

It is limiting to think only of race and gender when it comes to diversity, as it really refers to being able to bring different perspectives. In an organisation which has only engineers or only men or only one dominant ethnic group, anyone who doesn't belong to that group would likely feel excluded.

The inherent danger is that it leads in any profession to group-think. It is a known fact that the larger and more similar a group, the less likely individuals are to dissent. Groups can form norms and behaviors quickly and can develop blind spots quickly.

And nowhere is this clearer than minority protection, race or LGBTQ issues. Building an environment which is safe, whether in a family, organisation or society, means to build an environment in which people feel safe and valued as they are and feel – not how you pretend you would like them to be.

Symbolism matters in terms of equality - such as equal access to employment, housing or even social norms. I remember the outrage that Muslims felt as a result of 9/11. Many complained of being mistreated at immigration or visas, without being aware that they often practiced discrimination themselves.

We as a society have much to search within when it comes to these issues. The latest analytical thinking on this debate provides us the tools to confront such uncomfortable issues. Blatant persecution and discrimination can never be the answer – what may help us is to shift the paradigm to listen and have empathy. And above all, to recognise that diversity does not mean inferiority, and societies did not develop by practicing separatism.