I would never have written this piece, if it hadn’t been for a Google search. Having seen the site and returned from an enchanting trip to Lebanon, I searched for: “Mleeta resistance museum” – perhaps because I want to find out what the internet had to say about a place I’d just seen.

Inside Hezbollah’s Terror Tech Museum reads the search result from Wired magazine, right below Trip Advisor. Now, whatever I call it, I am pretty sure I could not be on the same page as Wired when it comes to describing it.

Of course, the worldview that gives rise to such headlines would not find this surprising. After all, I’m Pakistani. And this is the era when people take the ‘Clash of Civilisations’ thesis far more seriously than they ought to – with terrifying results worldwide.

***

No sooner had we landed at Beirut-Rafic Hariri International Airport, found ourselves a taxi and driven a few metres out, that the question came up. It came from the taxi driver, right after we had established that he could not communicate with me in English or French – leaving me with no option but to trudge along in my flawed Arabic. The question was one that I had not really planned to answer – at least not so soon.

I thought it might come up in a relaxed conversation with friends (old or new), or in the middle of some long political discussion over an arguila, once we had figured out how Beirut worked.

But it was question number 2. And it came in my first conversation since landing.

Number 1 was, of course, something for which I am generally well-prepared when travelling. “Where are you from?”

“Pakistan!” I always reply, with a pre-calibrated level of cheerfulness, hoping that they haven’t seen anything on the news from my part of the world recently.

And then came the question. “Oh. Are you Sunni or Shia?”

Here I was: already having to tackle an issue which is, to say the very least, complex, personal, political, fascinating, perilous, new and yet ages old…

Now at any given time, there are a number of voices in my head (all facets of my own personality, I suppose?) locked in argument.

Well…the cat’s out of the bag – you’re going to have to answer the taxi guy, Ziyad. And in Arabic too! Talk about hitting the ground running. Enjoy! sneered a voice in my head.

Replying to the taxi driver, I found myself falling back on my usual strategy – explaining the complicated background of my own family, and trying to appease both sides of the usual sectarian divide. Then I ask the person what side they belong to. And then I gradually play up an identification that would appeal to them.

I play this game because I can. My family background lends itself to a number of different sectarian and ethnic identifications.

I play this game because I must. The last thing one would want, if they could help it, is getting caught up in a vicious old sectarian feud with particularly vicious new characteristics.

As for the taxi driver, it turned out he was Shia. With my explanation complete, I added to the taxi driver: “But we are all Muslims! We are all brothers!”

And of course, he enthusiastically supported the sentiment, adding that it did not matter what sect one identified with.

Of course it doesn’t matter! says the voice in my head. That’s precisely why you made it question number 2, brother! Not “Which city are you from?” or anything like that…

***

Many days after our arrival, we are driving through Beirut, and our guide is identifying all the spots which the Israelis bombed in 2006. We have gotten along famously: myself, my life’s companion and our guide. He is Sunni – vocally so. We are travelling towards the south of the country, the Shia heartland, to visit the Tourist Landmark of the Resistance, which was described to us as a museum run by Hezbollah.

For this we will have to journey to the hilly site of Mleeta.

As we drive past a part of Beirut which had come under bombardment during Israel’s 2006 war in Lebanon, our guide remarks, “You know, they don’t bomb us! The Israelis don’t have any problem with us!” he smirks.

I am baffled for a moment. I thought he was just showing me where they bombed his city! I am about to ask “Who is ‘us’?”, but before I can utter it, I get my reply. “You know, their fight is with the Shias!”

He chuckles merrily.

He is such a merry man that I find myself smiling even when I am not particularly merry.

***

On our way south we munch upon the significant stockpile of food that we had saved from our second breakfast – saj, za’atar, mortadella, labneh, olives and kaak. It is a glorious repast, all wrapped up safely in aluminium foil. We also have ayran to wash it down. Yes, we had already had a first breakfast, which consisted of sausages, tomato, ful medames, hummus, eggs, bread, olives and some miscellaneous fruit.

What can I say? I eat a breakfast once every three months at home, or once every few days if I’m travelling. So I see no reason why it shouldn’t be an epic affair.

***

As we approach Mleeta, our guide guesses that this site celebrating Hezbollah and the Lebanese resistance would be the first to be hit by the Israelis in case they enter Lebanon again. He begins to point towards various hills and villages – the closer we get to Mleeta, the more animated his descriptions.

And then I realise: the closer we get, the more he is talking about “when we fought the Israelis here”. I cannot help but ask him about the shift in pronouns. Earlier in the day, driving through Beirut, it was “us” and “them” – Sunnis and Shias, people who don’t get targeted by Israel and people who do. So how exactly does he now talk about how “we” fought the Israeli occupation? I decide to just go ahead and ask him.

He smiles, because he gets exactly what I’m asking and why. “You know, when one sees the children bombed and killed by the Israelis…”

There is no merriment on his face any more. “Nobody likes to see children killed like that, you know? So… we! You understand?”

I do.

To walk through Mleeta is to believe: that David can take on Goliath and win. All around us, the military infrastructure of a brutal occupation lies scattered with triumphant carelessness

***

The drive to Mleeta takes us through core areas of support for Lebanon’s two main Shia Islamist forces: the older Amal, and the relatively newer, Hezbollah. Both participated in the resistance against the Israeli occupation of south Lebanon during the 1980s.

Every village we pass bears testament to the blood that was spilled in this resistance effort. Martyr posters adorn walls, squares and poles. Everywhere you go, you are greeted by the faces of the young people who, in fighting literally to the death, made the occupation untenable for the Israel Defence Force (IDF). The ‘date of martyrdom’ is mentioned on every poster it seems – in big broad writing.

As we drive into the large parking-lot outside the Hezbollah-run resistance museum in Mleeta, a sight greets our eyes that I had not quite expected. There is some sort of Israeli military vehicle lying in plain sight in the middle of the parking-lot, as if it had been forgotten or abandoned there. The Hebrew markings with numerals are clearly visible on it.

As we approach the entrance gates, we come upon a site labeled “The Well”. A signboard says that during the years of resistance against the Israelis, this was the only source of water for Mleeta. Knowing this, the Israelis on nearby hill positions had the well marked in their sights. The resistance fighters braved death to fetch water from the well. One cannot help but be immediately reminded of the imagery around Karbala and Yazid’s forces denying the Prophet’s (PBUH) family members access to the Euphrates for drinking water. The symbolism is inescapable for the visitor – one can only imagine how powerful it would have been for the young people of the south as they took up the fight against what was one of the most powerful militaries to set foot on Lebanon, the IDF.

The gate proclaims Mleeta as a place “Where Land speaks to Heaven”. We enter and a Hezbollah representative takes over immediately. With the greatest courtesy, he leads us to a cinema hall, where we sit in darkness and watch a video of welcome – addressed by none other than Hezbollah Secretary-General Hassan Nasrallah himself!

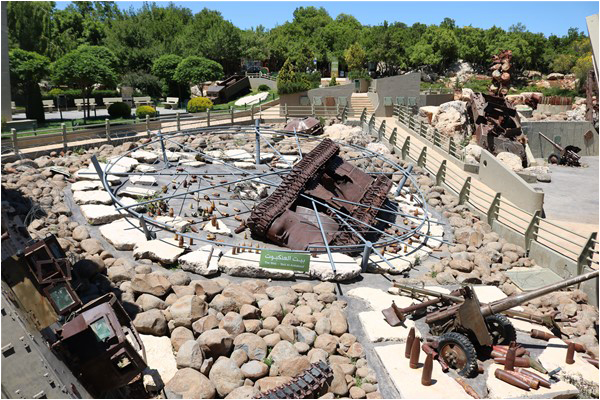

Mleeta is a powerful experience. There are those who dismiss it as mere ‘propaganda’. But I think it tells a story – a very important one. To walk through Mleeta is to believe: that David can take on Goliath and win. All around us, the military infrastructure of a brutal occupation lies scattered with triumphant carelessness. Hezbollah took the military equipment, vehicles and weapons that it captured from the Israeli forces and turned it into modern art installations.

“The Abyss” shows an Israeli Merkava tank sinking into a quagmire – the south of Lebanon and its indomitable people. “The Web” plays on a similar theme, showing Israeli armour trapped in a web of metal and destruction.

We walk along the meticulously-maintained path that Hezbollah fighters once took to get to the front-line. From here they kept the Israeli occupation forces preoccupied, while guerilla bands hit them where ever they spotted any vulnerability. Motorcycles were used to supply fighters in the difficult terrain.

The resistance fighters adopted the sparrow hawk as their symbol – a motif that appears again and again at Mleeta. Our Hezbollah guide informs us that this bird was frequently seen by fighters in the area. It is a stubborn bird – to get it to abandon its home is very difficult.

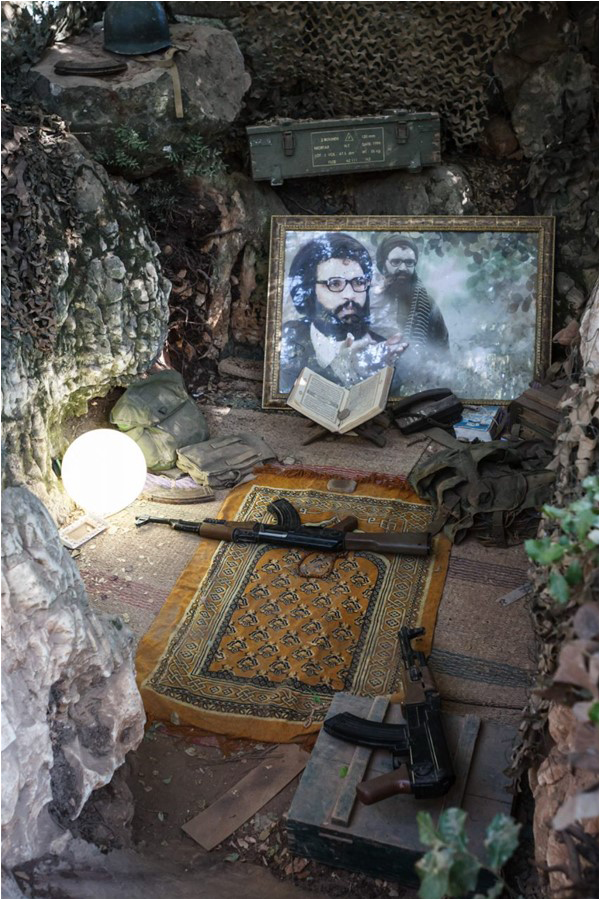

We come upon a spot where Abbas al-Mousavi, founder and Secretary-General of Hezbollah used to pray and rest while at the frontline. It is a touching display of Spartan simplicity– a prayer mat, a Quran, a satellite phone.

Mousavi died at the hands of the IDF in 1992.

***

In the areas of southern Lebanon that I travel through, where ever possible, I look very carefully at the martyr posters. And yet, I seem to find nothing after 2006.

Hezbollah, in particular, is known to have taken a very active role in the defence of the embattled Syrian regime – military analysts describe its role as decisive in preventing Bashar al-Assad from sharing a fate similar to Saddam Hussein or Muammar Gaddafi. It is well known that they have suffered losses in the fierce fighting in Syria for the past three to four years.

I ask around, and I am told that the group keeps its current involvement in Syria (and especially losses there) a low-key matter in Lebanon.

It is the maelstrom of militarised sectarian identities which Hezbollah now finds itself drawn into. Once it had gained immense support across sectarian lines in Arab and broader Muslim world for successfully resisting Israel in the 2006 incursion into Lebanon by the IDF. Today the group is aligned firmly with Iran in a titanic, deadly game of chess, with Saudi Arabia leading the opposite side. The battleground between Riyadh and Tehran consists of Muslim populations stretching all the way from Lebanon to Pakistan.

And the easiest way to project power for either side? That would be playing the age-old game of sectarian divides harnessed for political ends.

Henry Kissinger speaks of the situation in “the Middle East” as being similar to Europe during the Thirty Years War – the sectarian feuds between Catholic, Lutheran and Calvinist forces of Christianity.

Now, Kissinger might stand an ocean apart from me in worldview, but I am constrained to admit that he has a point about the logic of sectarian conflict and how it is increasingly tied to the strategic positions and goals of various Muslim countries from Lebanon to Pakistan. If that be the case, what exactly are we facing today?

Historian C. V. Wedgwood wrote in her famous study of the Thirty Years War and its millions of deaths:

“Morally subversive, economically destructive, socially degrading, confused in its causes, devious in its course, futile in its result, it is the outstanding example in European history of meaningless conflict.”

***

Two immensely powerful Turkic warlords found that the sectarian game worked very well for them in the 16th century. One was the ruler of the Ottoman empire, Yavuz Sultan Selim – known to the West as “the Grim”. The other was Shah Ismail, founder of the Safavid empire in what is today Azerbaijan and Iran.

The clash between the two men was certainly not about culture: Ismail wrote in a form of Azeri language, quite close to Turkish. Selim wrote back in Persian. The problem was ultimately this: who was to have dominance in eastern Anatolia, the Caucasus, Iraq and north-western Iran? The question is always something like that, is it not?

Ismail relied on the power of messianic teachings promoted by the Safavid order, in an area which was rife with all kinds of heterodox beliefs. The Safavids drew upon themes from Shi’ism, Sufism and on the battlefield, counted upon fanatically devoted warriors, the Qizilbash. Selim, meanwhile, relied on the power of Sunni religious orthodoxy, the well-oiled war-machine of the Ottoman empire and the world’s finest gunpowder weapons.

When supporters of the Safavids began a massive uprising in Anatolia (modern-day Turkey), it was too close to the Ottoman heartland for Selim to ignore. He decided to not only crush the rebels in his own domains in Anatolia, but also to finish the Safavid threat within modern-day Iran – once and for all.

There was one snag, though. While there had been many instances of infighting between various empires and sects of Muslims from the birth of Islam up to the 16th century, there was still no clear justification for fighting ‘fellow Muslims’. As befits someone described as ‘the Grim’, Selim and the Ottoman ulema decreed that the Qizilbash and others of their ilk were to be considered heretics, and therefore not Muslims at all – and that a war of extermination was quite acceptable against them.

Selim drew upon a fatwa whose language was chillingly close to the murderous rhetoric emanating from sectarian anti-Shia groups in Muslim countries today. One fatwa first lists out their alleged heresies and then concludes thus:

“…one should not listen to their repentances and regrets, but kill all of them. If it is known that there is any one of them or anyone who supports them in a certain town, they must be killed. This kind of population is both disbelieving and pagan; and at the same time, harmful. For these two reasons, it is necessary (wajib) to kill them…”

Selim’s successes were undeniable. He was able to put a cap on the Safavids’ expanding influence in Ottoman-ruled Anatolia. He crushed Ismail’s forces at the pivotal Battle of Chaldiran (1514). He was able to use his anti-Qizilbash fatwas to stamp out Shi’ite and pro-Safavid elements in Anatolia, ensuring that they would forever remain irritants rather than an existential threat to Ottoman power.

But what he could not do was to put an end to the Safavid empire in Iran – it survived. And part of its strategy for survival was to give permanent form to its borders with neighbouring Turkic Sunni empires. The Safavids made their borders permanent by vigorously promoting Twelver Shi’ism on the Iranian plateau and persecuting those who would not conform.

Both Ottomans and Safavids used sect to define themselves against the other, mark out their grand strategic goals and above all – to justify using fire and sword against internal dissent.

In 2011-12 AD, when Bashar al-Assad found his regime facing demise in the face of a rebellion, he played a card that Shah Ismail and Sultan Selim would have understood perfectly – turning a political clash into a religious-sectarian one and then identifying his regime with one side and the rebels with the other. In doing so, he gave the conflict (and his own regime) a certain permanence. He found allies (such as Hezbollah, Iran and others) and enemies almost pre-designed for the war he was going to fight.

The borders that Shah Ismail and his successors drew in the 16th century remain the political and sectarian borders today between Turkey, Iran and Iraq. One wonders how many centuries the bloody new battle-lines will last – those that were etched into the land by the Assad regime and the countries which oppose it.

***

A large number of classmates, insisting, in primary school, that I tell them whether I was Sunni or Shia. I had never been taught an answer to this question, probably because it was not easy.

“I am Muslim!” I insist in the sneering faces of classmates. My reply is greeted with hoots of laughter. One boy begins to explain to me that it doesn’t work this way. I have to be one or the other.

That night, I have many questions for my mother. All I want is a simple answer that makes me one or the other…

***

As you reach the end of the trail that takes you through the tunnels dug by the resistance fighters at Mleeta, you reach a gorgeous, well-tended garden near the top of the hill.

I sit here – mostly to rest from the long journey. But I also need to think.

From somewhere, the azaan begins to play on speakers. I wonder if it was motion-detectors or something else that made the mechanism work.

An insect that I cannot identify flies in out of nowhere as I sit and look at a flower. I back off. The insect seems proud, armoured. It buzzes and vibrates its wings as it sits, as if to tell me it is prepared for anything.

Vali Nasr has spoken extensively of how political vision, even morality itself, is now starting to be defined in sectarian terms in Muslim countries. Increasingly, there is no right or wrong, no dictators or freedom-fighters, no justice or oppression – only what works for your sect.

I think of the martyrs that Mleeta commemorates, as I sit in that hill garden. I fear that what they fought for will be forgotten. I fear that we will forget the spiritual diversity of our lands, replacing love of the neighbour with newer allegiances to transnational barbarisms. I fear that we will all become unwitting soldiers of Sultan Selim and Shah Ismail – long after they have ceased to care.

The writer may be reached at ziyadfaisal@gmail.com