As the incumbent government celebrates one year since it was brought to power and looks forward to many more, the truth is, they is little to show for all their pre-election bluster except for the “anti-corruption drive” that has resulted in most opposition leaders languishing behind bars. But the groundwork for this was laid before the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) government took reins of power in the country (and not by them).

The ethno-nationalist Baloch National Party’s Akhtar Mengal helped the PTI form the government in the centre but on the guarantee that the government would agree to his ‘six points’. One of the six demands was the release of all individuals who had been forcibly disappeared, an issue that has been kept in cold storage for a long time, even as the heinous practice continues unabated. After thanking the government for unconditionally acceding to all his demands, Mengal last year acknowledged that “this is a long-standing problem and will take at least one year to rectify.” That one year is now up.

In the immediate aftermath of the agreement, however, several of those disappeared miraculously “resurfaced.” Akhtar Mengal was roundly commended from all quarters and the Human Rights minister used these cases as proof of her government’s alacrity on the issue.

While they continued to play to the crowd, the actual issues were ignored. The questions that needed to be asked were: Why does this practice continue to happen at all in Balochistan and other parts of Pakistan and under what law does Pakistan strip her citizens of their basic human rights?

Balochistan has had an uneasy relationship with the Pakistani state. From the annexation of the state of Kalat into Pakistan proper in 1948, there have been numerous revolts against the state, which have been violently suppressed. That followed by decades of neglect makes Balochistan one of the poorest areas in the country, despite accounting for almost half its size. Little to no attention has been paid to the aspirations of the Baloch people, many areas are still without basic facilities such as electricity, clean drinking water or natural gas and modern modes of communication are blacked out. Balochistan consistently ranks as the worst in health and education in the country. Certain parts of Balochistan seem to take one back to what should be a bygone era.

The latest iteration of the Baloch insurgency has entered its thirteenth year, and while there have been ebbs and flows, it has not completely died out with spikes in insurgent attacks every now and then. The most worrying aspect for the Pakistani state is the support and involvement lent to the movement by educated middle and lower-middle class Baloch. The message relayed to the outside world, however, is that all is well.

If one was to observe what has transpired during the last decade or so, one would see past the eyewash. The truth is that situation on the ground has changed little, if at all. Neither the provincial or federal government has any say in the matter of missing persons (or other matters), nor has the practice ceased. Balochistan remains an information and administrative black hole, with government writ not extending beyond a few major districts. Police writ is non-existent, with a combination of the armed and paramilitary forces and tribal militias running the show. No local reporters are allowed to cover the missing persons issue and no international reporters allowed in the province at all. One must thus rely on independent reports or be force-fed the official line.

The Pakistani military apparatus has never been known for their nuance and diplomatic skills. Contrary to their claims, there have been reports of arbitrary detention of men, even women and children; villages have been under siege for days with no food, water or medical facilities available to hapless locals. Testimony from survivors paints a grim picture.

In the past, there have been rumours of state agencies colluding with militant Islamist groups to quell the unrest. In 2014, three mass graves in Khuzdar district containing, depending on who you ask, between 13 and 100 mutilated bodies were discovered near an alleged militant compound run by Shafiq Mengal, the notorious militant leader of the Lashkar-i-Jhangvi. Mengal was widely rumoured to be running a death squad in the province. The judicial commission formed by the government to probe the matter was predictably focused on proving the government and state security agencies’ innocence. Mengal still walks a free man, and was even running for election to the provincial assembly last year. The question, however, remains to this day, who did it then? Nobody seems to want to answer that question.

The blame for Balochistan, like all of Pakistan’s other problems, is laid at India’s door. Just last year, Justice (retd.) Javed Iqbal, head of a committee formed to probe missing persons and reigning DG NAB, said that “foreign intelligence agencies illegally apprehend people and pin the blame on Pakistan’s intelligence agencies.” Even if this was true, should it not have been a greater cause for concern that foreign intelligence agencies were covertly abducting Pakistani citizens from within the country? No statement supporting or refuting these claims was uttered by those in power.

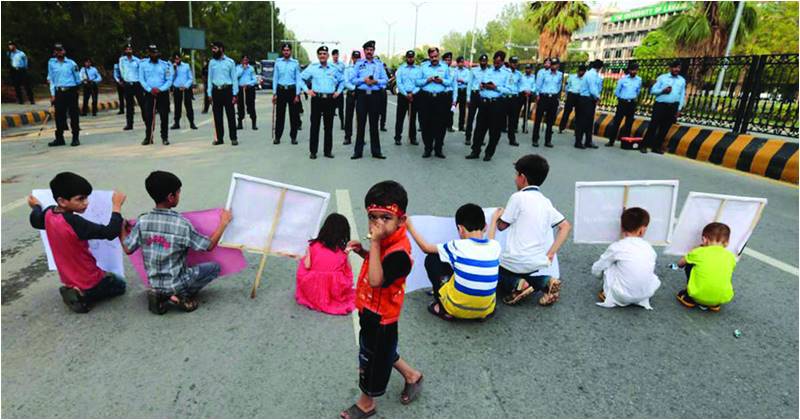

All this is made worse by promises made by elected officials. The current honourable Human Rights minister told a protest in Islamabad last year that the government would soon criminalise enforced disappearances. To this day, Pakistan is not a signatory to the International Convention on Enforced Disappearances.

It must also be stressed here that enforced disappearances are not only limited to Balochistan. The unrest over missing persons during the war on terror waged in erstwhile FATA led to the creation of the PTM. Sindhi Nationalists and MQM workers have also been forcibly disappeared. Others with alleged links to militant outfits have also been forcibly detained. Many remain missing to this day. Few return to tell of their ordeal.

The right to habeas corpus is guaranteed by Pakistan’s constitution. Yet constitutional protections against unlawful detention continue to be largely undermined by other legislation. These laws trample on universally accepted norms of human rights and liberties. The Protection of Pakistan Act 2014, akin to the US’s Patriot Act, is one such law, which superseded the infamous Anti-Terrorism Act (ATA) of 1997.

The provisions in these laws are sweeping, aimed at providing the intentionally vaguely termed “protection against waging of war against Pakistan,” and shift the burden of proof primarily on the accused. The PPO also provides for indefinite preventative detention as well as detention in undisclosed internment camps. Blanket immunity from prosecution is provided to security and intelligence agencies when they violate the rights to life and liberty.

Sadly for Pakistan, the legal fraternity, for the most part, also backed these laws when they were promulgated. ‘Leading lights’ of our judiciary such as Ali Zafar and Ahmer Bilal Soofi wrote op-eds and were seen on television justifying the need for stringent anti-terrorism legislation and drawing parallels with the USA, UK and India. Barring human rights groups and certain segments of the civil society, there was little protest.

Ali Zafar’s op-ed from that time makes for interesting reading. After first admitting that fundamental rights granted by the constitution were inalienable, he writes: “…the state comes before the constitution, law and human rights! If there is a threat to the country then there is no time to discuss legal niceties; people have to unite and accept the fact, without argument [emphasis added], that there is a need for laws, howsoever very harsh or rigid, which allow maximum leverage to the law-enforcing agencies and courts to bring perpetrators of terrorism to justice. Such laws may not strictly be kosher — they may encroach upon fundamental rights. But extraordinary situations need extraordinary laws.”

This narrative was used to justify the need for such sweeping laws in the ‘extraordinary situations’ such as the war waged by militant groups against the Pakistani state in FATA and adjoining districts in the past 15 or so years and later, after the APS massacre in December 2014, the need for military courts and reinstitution of capital punishment. TV and print media were used to hammer this message into the peoples’ minds. A large segment of the Pakistani public has come to accept these acts as a ‘necessary evil’, and lent their support. DG ISPR Maj. Gen Asif Ghafoor’s recent remarks in a press conference that “all is fair in love and war” when referring to enforced disappearances were reflective of the hubris attained from the knowledge of being well and truly above any reprimand.

Those who have tried to draw the state’s attention to these violations have been verbally and physically threatened or charged with anti-state activities and thrown in jail, and in an ironic twist, been ‘disappeared’ themselves. Mama Qadeer was labelled a RAW agent and continually harassed by law enforcement agencies when he led his long march for missing persons. The PTM leadership is accused by the state of working on NDS’s payroll and its leaders languish in jail or face criminal cases over trumped up charges of sedition and anti-state activities.

So a year on into what was supposed to herald change for the people of Pakistan, there is still no closure for those who have lost their loved ones to the ‘midnight rap on the door’ nor have those responsible been brought to book. Moreover, the practice of enforced disappearances has still not been criminalized and continues to this very day. It is a blot on our country’s human rights record and, as citizens, our collective conscience.

The ethno-nationalist Baloch National Party’s Akhtar Mengal helped the PTI form the government in the centre but on the guarantee that the government would agree to his ‘six points’. One of the six demands was the release of all individuals who had been forcibly disappeared, an issue that has been kept in cold storage for a long time, even as the heinous practice continues unabated. After thanking the government for unconditionally acceding to all his demands, Mengal last year acknowledged that “this is a long-standing problem and will take at least one year to rectify.” That one year is now up.

In the immediate aftermath of the agreement, however, several of those disappeared miraculously “resurfaced.” Akhtar Mengal was roundly commended from all quarters and the Human Rights minister used these cases as proof of her government’s alacrity on the issue.

To this day, Pakistan is not a signatory to the International Convention on Enforced Disappearances

While they continued to play to the crowd, the actual issues were ignored. The questions that needed to be asked were: Why does this practice continue to happen at all in Balochistan and other parts of Pakistan and under what law does Pakistan strip her citizens of their basic human rights?

Balochistan has had an uneasy relationship with the Pakistani state. From the annexation of the state of Kalat into Pakistan proper in 1948, there have been numerous revolts against the state, which have been violently suppressed. That followed by decades of neglect makes Balochistan one of the poorest areas in the country, despite accounting for almost half its size. Little to no attention has been paid to the aspirations of the Baloch people, many areas are still without basic facilities such as electricity, clean drinking water or natural gas and modern modes of communication are blacked out. Balochistan consistently ranks as the worst in health and education in the country. Certain parts of Balochistan seem to take one back to what should be a bygone era.

The latest iteration of the Baloch insurgency has entered its thirteenth year, and while there have been ebbs and flows, it has not completely died out with spikes in insurgent attacks every now and then. The most worrying aspect for the Pakistani state is the support and involvement lent to the movement by educated middle and lower-middle class Baloch. The message relayed to the outside world, however, is that all is well.

If one was to observe what has transpired during the last decade or so, one would see past the eyewash. The truth is that situation on the ground has changed little, if at all. Neither the provincial or federal government has any say in the matter of missing persons (or other matters), nor has the practice ceased. Balochistan remains an information and administrative black hole, with government writ not extending beyond a few major districts. Police writ is non-existent, with a combination of the armed and paramilitary forces and tribal militias running the show. No local reporters are allowed to cover the missing persons issue and no international reporters allowed in the province at all. One must thus rely on independent reports or be force-fed the official line.

The Pakistani military apparatus has never been known for their nuance and diplomatic skills. Contrary to their claims, there have been reports of arbitrary detention of men, even women and children; villages have been under siege for days with no food, water or medical facilities available to hapless locals. Testimony from survivors paints a grim picture.

In the past, there have been rumours of state agencies colluding with militant Islamist groups to quell the unrest. In 2014, three mass graves in Khuzdar district containing, depending on who you ask, between 13 and 100 mutilated bodies were discovered near an alleged militant compound run by Shafiq Mengal, the notorious militant leader of the Lashkar-i-Jhangvi. Mengal was widely rumoured to be running a death squad in the province. The judicial commission formed by the government to probe the matter was predictably focused on proving the government and state security agencies’ innocence. Mengal still walks a free man, and was even running for election to the provincial assembly last year. The question, however, remains to this day, who did it then? Nobody seems to want to answer that question.

The blame for Balochistan, like all of Pakistan’s other problems, is laid at India’s door. Just last year, Justice (retd.) Javed Iqbal, head of a committee formed to probe missing persons and reigning DG NAB, said that “foreign intelligence agencies illegally apprehend people and pin the blame on Pakistan’s intelligence agencies.” Even if this was true, should it not have been a greater cause for concern that foreign intelligence agencies were covertly abducting Pakistani citizens from within the country? No statement supporting or refuting these claims was uttered by those in power.

All this is made worse by promises made by elected officials. The current honourable Human Rights minister told a protest in Islamabad last year that the government would soon criminalise enforced disappearances. To this day, Pakistan is not a signatory to the International Convention on Enforced Disappearances.

It must also be stressed here that enforced disappearances are not only limited to Balochistan. The unrest over missing persons during the war on terror waged in erstwhile FATA led to the creation of the PTM. Sindhi Nationalists and MQM workers have also been forcibly disappeared. Others with alleged links to militant outfits have also been forcibly detained. Many remain missing to this day. Few return to tell of their ordeal.

The right to habeas corpus is guaranteed by Pakistan’s constitution. Yet constitutional protections against unlawful detention continue to be largely undermined by other legislation. These laws trample on universally accepted norms of human rights and liberties. The Protection of Pakistan Act 2014, akin to the US’s Patriot Act, is one such law, which superseded the infamous Anti-Terrorism Act (ATA) of 1997.

The provisions in these laws are sweeping, aimed at providing the intentionally vaguely termed “protection against waging of war against Pakistan,” and shift the burden of proof primarily on the accused. The PPO also provides for indefinite preventative detention as well as detention in undisclosed internment camps. Blanket immunity from prosecution is provided to security and intelligence agencies when they violate the rights to life and liberty.

Sadly for Pakistan, the legal fraternity, for the most part, also backed these laws when they were promulgated. ‘Leading lights’ of our judiciary such as Ali Zafar and Ahmer Bilal Soofi wrote op-eds and were seen on television justifying the need for stringent anti-terrorism legislation and drawing parallels with the USA, UK and India. Barring human rights groups and certain segments of the civil society, there was little protest.

Ali Zafar’s op-ed from that time makes for interesting reading. After first admitting that fundamental rights granted by the constitution were inalienable, he writes: “…the state comes before the constitution, law and human rights! If there is a threat to the country then there is no time to discuss legal niceties; people have to unite and accept the fact, without argument [emphasis added], that there is a need for laws, howsoever very harsh or rigid, which allow maximum leverage to the law-enforcing agencies and courts to bring perpetrators of terrorism to justice. Such laws may not strictly be kosher — they may encroach upon fundamental rights. But extraordinary situations need extraordinary laws.”

This narrative was used to justify the need for such sweeping laws in the ‘extraordinary situations’ such as the war waged by militant groups against the Pakistani state in FATA and adjoining districts in the past 15 or so years and later, after the APS massacre in December 2014, the need for military courts and reinstitution of capital punishment. TV and print media were used to hammer this message into the peoples’ minds. A large segment of the Pakistani public has come to accept these acts as a ‘necessary evil’, and lent their support. DG ISPR Maj. Gen Asif Ghafoor’s recent remarks in a press conference that “all is fair in love and war” when referring to enforced disappearances were reflective of the hubris attained from the knowledge of being well and truly above any reprimand.

Those who have tried to draw the state’s attention to these violations have been verbally and physically threatened or charged with anti-state activities and thrown in jail, and in an ironic twist, been ‘disappeared’ themselves. Mama Qadeer was labelled a RAW agent and continually harassed by law enforcement agencies when he led his long march for missing persons. The PTM leadership is accused by the state of working on NDS’s payroll and its leaders languish in jail or face criminal cases over trumped up charges of sedition and anti-state activities.

So a year on into what was supposed to herald change for the people of Pakistan, there is still no closure for those who have lost their loved ones to the ‘midnight rap on the door’ nor have those responsible been brought to book. Moreover, the practice of enforced disappearances has still not been criminalized and continues to this very day. It is a blot on our country’s human rights record and, as citizens, our collective conscience.