“Carry life as you walk, and carry the firmament too

Walk so, that the entire world should choose to walk with you”

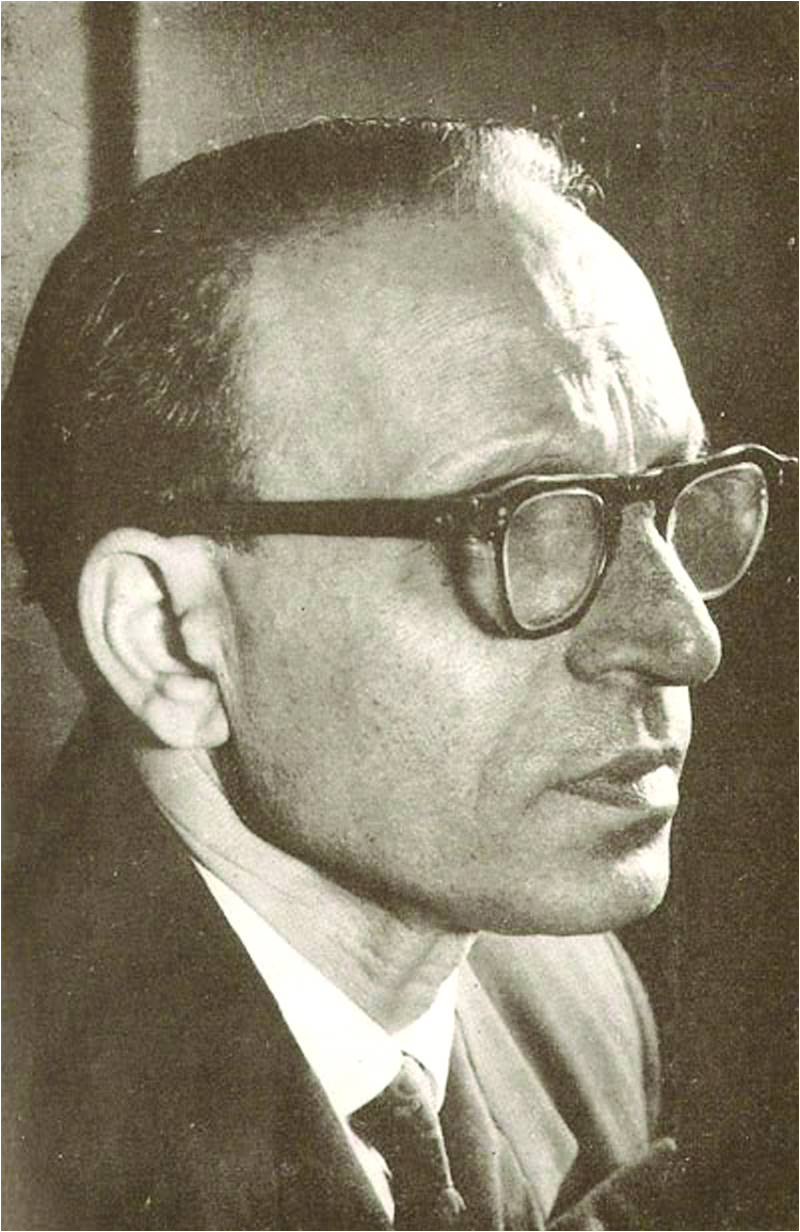

The scene is from 1935. A rainy July evening in a vast hall at a mushaira in Hyderabad Deccan. A poet, unknown for a certain prominent member of the audience, recites his poem, “Here in the fields ashore the water, I still remember.” That poet was Makhdoom Mohiuddin, who passed away 50 years ago on the 25th of August at merely 61 years of age. The member of the audience was none other than Sibte Hasan, one of the pioneers of the Progressive Writers Association, as well as a founder of the Communist Party of Pakistan. And my first introduction to Makhdoom was indeed in Sibte’s beautiful book about the final days of the stultifying atmosphere of the Asif Jahi dynasty in Hyderabad Deccan, Shahr-e-Nigaran (Beloved City). The aforementioned poem had previously been published with the title of Toor (Mount Toor) in the late journal Aivaan and was read with relish by many of Sibte Hasan’s generation at Aligarh.

How many destinations did Makhdoom’s poetry travel in merely eight years from that appearance in 1935 to 1943; how many crossroads it passed through! But then one also thinks how many destinations our society had negotiated in those eight years, how many crossroads it passed through, how many times it tripped and in what a vortex of mental degradation and moral defeat it was trapped in then! The pen of even the greatest poets of that time could not have described the anguish, restlessness and struggle of that society with full force. But blessed are the people whose hands have been on the pulse of the period and while they may not have control over hastening the speed of time, but at least try to walk by matching its pace, feeling its heartbeat. And for this reason, one really adores Makhdoom’s verses from that period.

If someone had queried Makhdoom about whether the greatest reality is life or the evolution of life – he would have said that life and its evolution were two very different matters. We know what he would have said to those writers and artists who are alive but are carefree of all the responsibilities of time and space. However much the speed of life increases, however extreme the sorrows of life do become, they indeed find no respite from narrating the experiences of the pages from their tale of sorrow. Are these people not sincere about their art? Do they only do poetry because they can do nothing else? Or perhaps to correct the metre of their verses had become their second habit?

Let us leave aside this matter, for here we are talking about Makhdoom’s decade-old poetic life. It will be decided by the literary historian indeed what effect his poetry had on the thought and action of the Indian youth – especially the youth of the Deccan. But we can say without fear of refutation that Makhdoom’s poetry was definitely the reflection of the anguish and emotion of that era. His artistic consciousness is definitely seen to be convulsing everywhere with the spirit of social consciousness.

Many thoughts were common to most of our writers of that period. The feeling of rebellion against the curses of slavery, the feeling of rebellion against the traditional, obsolete and injurious values of society and then a foggy concept of a free and radiant future – this was a triangular axis, on which our social life and fine arts both were revolving. One angle of this triangle was the favourite of most of our young poets of the time; the angle of rebellion against traditional values. Every youth who has been in love and been unsuccessful, knows what blows have been struck by the traditional values of society on their love life. The opposition of family, fear of disrepute, lack of moral courage, a feeling of class unevenness, in fact God knows how many elements exist due to which the heart of love has been bloodied. If one looks at the literary journals and collections of that period, many such poems will be found where these social restrictions have been fumed against; even Makhdoom’s poems of those days are not devoid of the feeling of deprivation. And how could they not be? The beginning of youth, the initiation of love, the intensity of emotions, then the ability to adjust the emotions arising in the heart, then how could the arrow miss its target? The moments of Intezaar (The Wait) were passed,

“All night, in my moist eyes you continued to sway

Like my breath, you kept coming and going away”

And just note the creation of beauty indeed that a shehnai struck up, and sadness gave way to relief; and when she arrives after a long time of waiting, the poet who is in the business of love “bowed” and when she went away, the poet begins to remember those moments: this is how we met, how we talked, how we made love, how we sat ashore the water but,

“Neither those fields nor the flowing water remain

But a hazy mark of that bygone pleasure marks the domain”

One is grateful that in Makhdoom’s poems of that period the bitterness of past memory and mental illness is not reflected but it seems that the poet is content with these experiences; he neither hates these emotions arising in life nor is he embarrassed over them but remembers and relishes them.

Makhdoom felt this impending danger earlier than most. After Mussolini invaded Ethiopia, he wrote his impassioned Jang (War), perhaps the first Urdu poem against fascism

I have a complaint against most young poets of that time: that they had created a strange standard of love. According to them, in that revolutionary period, “for them” meaning “for men”, it was not proper to fall for the “thought” of the love of women. That was the time for action. Yes! After making the revolution, it would be seen when they would have some leisure. So many poets instructed their benevolent beloveds with great pride and paternal love to go home; because they did not have the strength to walk side-by-side with the former; although when they would get relief from revolution, they will come. Poor self-deluded poets! While at the opposite, one remembers a verse of Makhdoom,

“Everywhere is spread the moonlight

As if she herself is with me, her youth alongside”

Makhdoom’s observation, experience and angle of sight never fell victim to such a mental illness, which would have affected his poetry. His love and concept of life and the consciousness of societal struggle were all life-giving. That is the reason that when the peace-wrecking and civilization-burning storms of fascism began to rage, Makhdoom felt this impending danger earlier than most. After Mussolini invaded Ethiopia, he wrote his impassioned poem Jang (War),

“From the mouth of the cannon emerged the melody of destruction

In the garden of the world spread the hellfire of ruination”

This was probably Makhdoom’s first political poem and the first call of protest against fascism in Urdu poetry; but in the final verses of this poem the same powerlessness and helplessness emerges which was prevalent at that time over our entire nation. Fascism was proceeding along with its devastation and Europe’s imperialist powers – Britain and France – were engaged in appeasing that fascism. They were strengthening it by constantly feeding this hungry demon with the blood of humanity. The Indian nation was a supporter of the freedom of Ethiopia and wanted to help it, but was constrained by its slavery to British imperialism; it had no power to free itself to fight fascism.

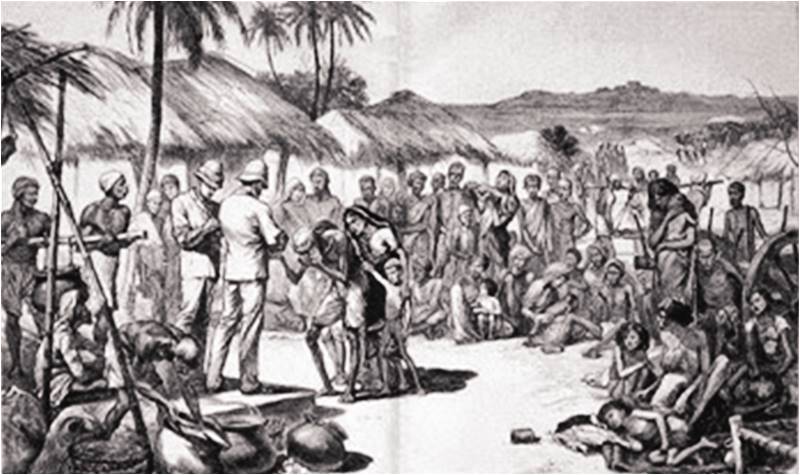

This reaction of helplessness revealed in Mashriq (The East) and with complete bitterness before those people who sung the praises of the historic greatness of the East; he presented the East in a new form and said see this is your East:

“The home of backwardness, hunger, beggary, illness filth

The crematory of life, freshness, intelligence and wisdom

A colorless and spiritless shell of a figure of the past

A death without resurrection, a noiseless drum

An endless night without dawn

A land nourishing the dreams of the Seven Sleepers of Kahf”

But the poet is not hopeless, he knows that every night, be it the night of separation, keeps nourishing a new dawn in its womb and he has hope rather he is certain that,

“This death-bred land will be made to fall

A new world, a new Adam to be made in its thrall”

How? When and where? Indeed even he does not know but he put faith in human evolution. He trusted the people and their growing confidence. Perhaps on this basis he often repeated this idea, this love of the future, and when the feeling of helplessness intensified, mental rebellion did not find a constructive route, the chains of slavery began to tighten further. Or there was a conflict between “the height of passion and the depth of determination” and then the fire burning within the heart of the poet despite social and political restrictions, to quench which he became a victim of niraaj or terrorism – literary terrorism – he become a balladeer for sabotage,

“Blow up the palace if such be the spectacle of existence

If such be the world itself seize its sustenance”

How much thunder there is in this verse! How much force, how much prophetic self-confidence; but in this flood of emotions, in this storm of sincerity heightened to the point of madness, one seeks in vain for the boat of reason. Maut ka Geet (The Song of Death) is very ear-pleasing; one’s blood boils upon listening to it but if raised to the criteria of reason, we will know that the poet is relishing death. If I am not wrong, the main idea of many of Makhdoom’s poems from this period was indeed this literary terrorism. But this period of his poetry did not last very long. Reason and madness harmonized quickly. Qamar (The Moon) was perhaps a memorial of this union. Note just two or three verses in which two sides of beauty, two angles of life have been shown,

“The new life is beckoning me, hear

The night is sad, there is poverty and slavery too

The moon, deshrouded, is too afraid to show

Where is the rosy-faced cupbearer and the ‘red wine’

The moon is narrating the fable of the sorrow of life”

This was the time when a wave of awakening was running through not just Hyderabad but the entire country. Popular forces were rising, class struggle was increasing. The slogans of “Inquilab Zindabad” were being raised in the air with new majesty. Peasants and workers were rising up for having their rights accepted. Those desires which the Indian nation had nourished for long feeding its heart’s blood, were now about to flourish. Perhaps affected by these conditions, Makhdoom wrote many national poems, out of which I especially like Hindustan Ki Jai (Victory to India). When Makhdoom would sing this poem in a chorus in students’ assemblies, an ecstatic scene would be created,

“That Indian youth, the bearer of freedom

The guardian of the nation and the jeweled sword, freedom”

At the same time, Makhdoom had written a brief poem on the struggle between the peasant and landlord, the struggle between the master and slave which was later titled Dhuaan (Smoke) but had a different title at that time. The circumstances of revelation behind this poem and its original title were known to merely a handful of people, and given that most of Makhdoom’s contemporaries have since passed away, will remain forever a secret,

“Yes there indeed my afflicted heart saw this too

Yes my guilty eye saw this too

Within the blood of the peasant, dreams of wealth did choke

Everywhere the burning corpse of justice went up in smoke”

But not many days afterwards, the clouds of war began to hover over the smoke of this corpse and Europe’s surroundings became dark. The status-quo powers which were concerned with countering the Soviet Union up to that point in time, now confronted each other. The capitalist system faced a deep crisis; it began to pluck out its own flesh with its teeth. Note two verses from Zulf-e-Chaleepa (Crooked Curl),

“It is the dance of gold, a dance of profit and loss

The dance of sudden death in every lane across

Had never seen before in disorder the bent tress

Had seen disorder, but not such distress”

In the period of the war, hardly half a dozen such poems were written which laid bare the actual reality of this war. Makhdoom perhaps had written three or four poems in this period. Zulf-e-Chaleepa, Sipaahi (Soldier) and Raat ke Haath men Ik Kaasa-e-Daryoozagari (A Begging Bowl in Night’s Hand) neither possess soldierly splendour nor “war-mongering” self-confidence, but the exact opposite, i.e. sadness and misery. Even then the novelty of its simplicity, and metaphors and representation is praiseworthy,

“Why are these vistas so fearful?

Why do the stars move with such dread?

Is youth being murdered here?

The borders of clothing are blood red”

Such a map of war had very rarely been witnessed.

Artistically speaking, “A Begging Bowl in Night’s Hand”, in my opinion, is among Makhdoom’s best poems. Alas one is forced to make do with just the last verse of the poem,

“The crowd of distressed stars on the forehead of the night

Only until the bright sun reveals its light”

This artistic hair-splitting aside, an interesting note must be shared here. Did Makhdoom have any idea which poem made him a beloved and popular poet among the people of India? Millions of peasants and workers indeed had no idea about who was the writer of this poem? But looking at the reports of the meetings recorded at the time, it was often mentioned that the proceedings of the meeting began with Ye Jang hai Jang-e-Azaadi (This War is the War for Freedom) which was sung by a team of five boys, a troop of ten girls together; perhaps the correspondent himself had no idea that this poem belonged to Makhdoom. This certificate of popular acceptance outweighed thousands of literary critiques; many of Makhdoom’s own comrades participated in many such meetings and recorded that when the troop of singers reached this stanza,

“Behold, the red dawn arrives

Of freedom, of freedom

It sings the flower-red song

Of freedom, of freedom

Look, the banner waves in the sky

Of freedom, of freedom”

Then often it happened that the same verses were repeated from various corners of the meeting and the listeners themselves became the reciters.

It remained the fashion at many a communist gathering to recite Makhdoom’s masterpiece Stalin ki Aavaaz (Stalin’s Voice) during that time at events celebrating the birthday – and later commemorating the death of - Joseph Stalin. In this poem Makhdoom’s poetry with all its qualities – its boundless sincerity, enhanced love of truth and self-confidence – ‘made its appearance’. This poem is a very good example of revolutionary realism:

“Should I become a silent spectator of this battle?

Should I put heaven under hell’s death rattle?

Should I not prove my own mettle?”

Recently, here in Lahore, at our own little commemoration of Makhdoom’s 50th death anniversary at the Pak Tea House in Lahore, I got into an argument with a gentleman about Makhdoom’s poetry. He was very offended with the latter’s artistic weaknesses. I said his command was appropriate and accurate; Makhdoom did not choose words carefully, sometimes compositions were loose, the idioms clumsy. But despite these weaknesses, he could not deny Makhdoom’s originality of thought, literary honesty and sincerity and self-confidence. That indeed was the “result of his date and year”; for artistic weaknesses indeed are themselves swept away like dry leaves. As I write these final lines of Makhdoom’s tribute, news has just come in that another “Mohiuddin”, another one of our heroes of the socialist movement, a voice for the downtrodden, a champion of labour rights and democracy, a campaigner for peace in South Asia, a true dervish and a personal friend and mentor to many in South Asia, Biyyathil Mohyuddin Kutty (also known as B.M. Kutty), has passed away in Karachi at 89. As a rare Malayali who relished progressive Urdu poetry, Kutty would have seconded that.

Note: All the translations from the Urdu are the writer’s own.

Raza Naeem is a Pakistani social scientist, book critic and award-winning translator and dramatic reader currently based in Lahore, where he is also the President of the Progressive Writers Association. He can be reached at: razanaeem@hotmail.com.