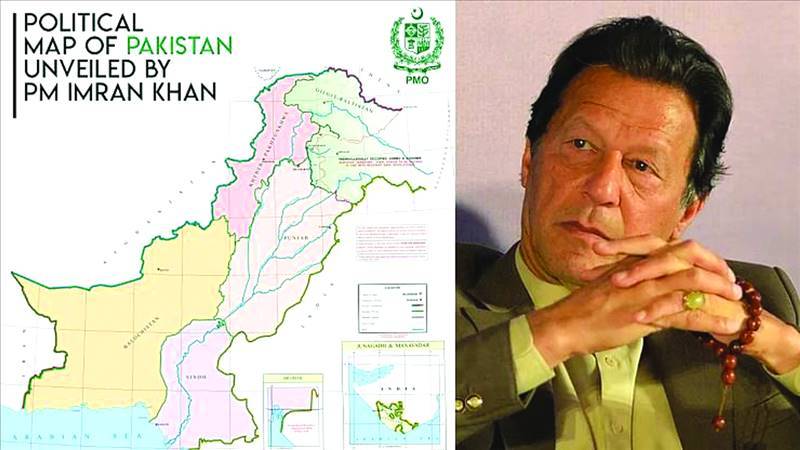

Pakistan issued an official map on Tuesday, August 4. The act, and the map itself, was widely misunderstood and misinterpreted in the country. The reactions ranged from ignorant comments on the social media to snide remarks from opposition parties. The government’s weak communication strategy and the political fault-lines that have deepened in the past two years didn’t help either. As a result, a very important exercise in expressing the sovereignty of a state became unnecessarily politicised.

Let’s set the record straight.

First, the Survey of Pakistan is the sole national mapping and land surveying agency in Pakistan. SOP is, therefore, the only agency that can delineate and demarcate Pakistan’s international borders, carry out topographic surveys, prepare national geographical database and publish maps of Pakistan.

It was vital to issue a standardised map for the following reasons:

A clear, standardised political map is thus a national requirement both for (geo)political and legal reasons. It voices a political narrative, which is important not merely to state facts but also as a legal instrument. It becomes part of what International Law describes as state practice and which can, given the wider acceptance of the practice, create opinio juris, i.e., “a subjective acceptance of the practice as law by the international community.”

Let’s now get to the map itself.

Leaving aside the unfortunate remarks that followed the issuance of the map, it is not very different from the standard map used and published by the Survey of Pakistan. However, the differences which exist are important.

One, the new map records Pakistan’s response to India’s decision in August 2019 to wipe out Kashmir’s special status under the Indian Constitution and instead simply incorporate it within India. The new map thus no longer refers to all of “Jammu & Kashmir” as “Disputed Territory” but specifically refers to AJK and Gilgit Baltistan as separate entities and demarcates them both in relation to each other as well as in relation to the “Line of Control.” The new map then refers to the remaining area of “Jammu & Kashmir” as “Indian Illegally Occupied Jammu & Kashmir”. It further clarifies that this area is “Disputed Territory – Final Status to be Decided in line with Relevant UNSC Resolutions.” In short, the new map converts Pakistan’s stated, textual position in relation to India’s illegal occupation of Jammu & Kashmir into clear graphics.

This point is very important because the map does not reduce the dispute to a territorial one but, nonetheless, seeks to reject India’s territorial claim while reiterating Pakistan’s official position that a final settlement has to be on the basis of the Kashmiris exercising their inalienable right to self-determination — as described in the UNSC Resolutions.

Another important development — long overdue — is the extension of the Line of Control beyond NJ980420 to the Karakoram Pass. This was the northeastern most point where the LoC ended. Previously, the area further north/northeast was not shown by any line. This map does so. This is in keeping with Pakistan’s position, though up until now the line that separates the Pakistan and Indian positions along the Saltoro Range conflict area was generally referred to as Actual Ground Position Line. That has been taken care of.

The extension of the line to Karakoram Pass is also important because one of the reasons India moved into Siachen in 1984 was to avoid that link-up. Given developments in eastern Ladakh, this is important.

The line for Sir Creek has been shown to lie on the eastern bank. This is a clear rejection of India’s claim that the boundary lies on the western bank and also shows that Pakistan continues to reject negotiating that dispute on the basis of Thalweg (also Talweg) doctrine. In geography, a thalweg is a line of lowest elevation in a valley or a watercourse. Under International Law, the thalweg generally constitutes the boundary between two states.

But while this is a generally accepted principle, in the case of Sir Creek, when a dispute arose between Sindh and the Kutch Darbar (over collecting firewood, such being the irony), the settlement, in 1914, was made on the basis of a compromise. The Sindh government was to forgo its claim on Kori Creek, further east of Sir Creek “to acquire ownership over the entire Sir Creek”.

The other obvious change is the removal from the previous map if what was known as Federally Administered Tribal Areas. They are now part of Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa.

This, then, is an overview of why the government deemed it imperative to issue a standardised political map of Pakistan. But the reactions that I have talked about should indicate to the government that if it wants to stand up to the challenges facing Pakistan, Prime Minister Imran Khan will have to make a decision: either keep hounding the political opposition by using a partisan and much-reviled National Accountability Bureau or reach out to the opposition and partner with it at least on those issues of national security and foreign policy that require a non-partisan approach.

Mr Khan cannot expect Pakistan to face the world as a united entity if he continues to harass his political opposition.

The writer is a former News Editor of The Friday Times. He reluctantly tweets @ejazhaider

Let’s set the record straight.

First, the Survey of Pakistan is the sole national mapping and land surveying agency in Pakistan. SOP is, therefore, the only agency that can delineate and demarcate Pakistan’s international borders, carry out topographic surveys, prepare national geographical database and publish maps of Pakistan.

It was vital to issue a standardised map for the following reasons:

- A political map expresses the sovereignty of a state and presents its sovereign claim to the outside world. This expression is as valid with reference to areas actually under the de facto and de jure control of a state as it is with respect to any areas that might be disputed. Take Nagorno Karabakh for example, an area under the control of a separatist Armenian majority that has wrested control of it from Azerbaijan. The area is internationally recognised as belonging to Azerbaijan, even though Baku does not control it.

- A standardised map is crucial to prevent incorrect maps being used in the country. This was actually happening and only recently the Punjab government confiscated certain books which showed three or four different and differing versions of Pakistan’s boundaries.

- A standard map is also imperative for a country’s position on its borders and claims in relation to the outside world.

- The point above acquired urgency in view of the issuance of maps by India post-August 5 that showed the illegally annexed areas of Jammu and Kashmir (including Ladakh) as well as the liberated areas of Asad Kashmir and Gilgit-Baltistan and Aksai Chin as belonging to India. It was crucial for Pakistan to set the record right in relation to India’s illegal and irredentist move.

A clear, standardised political map is thus a national requirement both for (geo)political and legal reasons. It voices a political narrative, which is important not merely to state facts but also as a legal instrument. It becomes part of what International Law describes as state practice and which can, given the wider acceptance of the practice, create opinio juris, i.e., “a subjective acceptance of the practice as law by the international community.”

Let’s now get to the map itself.

Leaving aside the unfortunate remarks that followed the issuance of the map, it is not very different from the standard map used and published by the Survey of Pakistan. However, the differences which exist are important.

One, the new map records Pakistan’s response to India’s decision in August 2019 to wipe out Kashmir’s special status under the Indian Constitution and instead simply incorporate it within India. The new map thus no longer refers to all of “Jammu & Kashmir” as “Disputed Territory” but specifically refers to AJK and Gilgit Baltistan as separate entities and demarcates them both in relation to each other as well as in relation to the “Line of Control.” The new map then refers to the remaining area of “Jammu & Kashmir” as “Indian Illegally Occupied Jammu & Kashmir”. It further clarifies that this area is “Disputed Territory – Final Status to be Decided in line with Relevant UNSC Resolutions.” In short, the new map converts Pakistan’s stated, textual position in relation to India’s illegal occupation of Jammu & Kashmir into clear graphics.

This point is very important because the map does not reduce the dispute to a territorial one but, nonetheless, seeks to reject India’s territorial claim while reiterating Pakistan’s official position that a final settlement has to be on the basis of the Kashmiris exercising their inalienable right to self-determination — as described in the UNSC Resolutions.

Another important development — long overdue — is the extension of the Line of Control beyond NJ980420 to the Karakoram Pass. This was the northeastern most point where the LoC ended. Previously, the area further north/northeast was not shown by any line. This map does so. This is in keeping with Pakistan’s position, though up until now the line that separates the Pakistan and Indian positions along the Saltoro Range conflict area was generally referred to as Actual Ground Position Line. That has been taken care of.

The extension of the line to Karakoram Pass is also important because one of the reasons India moved into Siachen in 1984 was to avoid that link-up. Given developments in eastern Ladakh, this is important.

The line for Sir Creek has been shown to lie on the eastern bank. This is a clear rejection of India’s claim that the boundary lies on the western bank and also shows that Pakistan continues to reject negotiating that dispute on the basis of Thalweg (also Talweg) doctrine. In geography, a thalweg is a line of lowest elevation in a valley or a watercourse. Under International Law, the thalweg generally constitutes the boundary between two states.

But while this is a generally accepted principle, in the case of Sir Creek, when a dispute arose between Sindh and the Kutch Darbar (over collecting firewood, such being the irony), the settlement, in 1914, was made on the basis of a compromise. The Sindh government was to forgo its claim on Kori Creek, further east of Sir Creek “to acquire ownership over the entire Sir Creek”.

The other obvious change is the removal from the previous map if what was known as Federally Administered Tribal Areas. They are now part of Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa.

This, then, is an overview of why the government deemed it imperative to issue a standardised political map of Pakistan. But the reactions that I have talked about should indicate to the government that if it wants to stand up to the challenges facing Pakistan, Prime Minister Imran Khan will have to make a decision: either keep hounding the political opposition by using a partisan and much-reviled National Accountability Bureau or reach out to the opposition and partner with it at least on those issues of national security and foreign policy that require a non-partisan approach.

Mr Khan cannot expect Pakistan to face the world as a united entity if he continues to harass his political opposition.

The writer is a former News Editor of The Friday Times. He reluctantly tweets @ejazhaider